Violence, illusion marked a dictator

Within days of taking power, Saddam Hussein summoned about 400 top officials and announced he had uncovered a plot against the ruling party. The conspirators, he said, were in that very room.

As the 42-year-old Saddam coolly puffed on a cigar, names of the supposed plotters were read out. As each name was called, secret police led them away. Twenty-two people were executed. To make sure Iraqis got the word, Saddam videotaped the entire proceeding and distributed copies across the country.

The plot claim was a lie. But in a few terrifying minutes on July 22, 1979, Saddam eliminated his potential rivals, consolidating the power he wielded until the Americans and their allies drove him from office a generation later.

Saddam, who was hanged today at age 69, ruled Iraq with singular ruthlessness. No one was safe. His two sons-in-law were killed on Saddam’s orders after they defected to Jordan but returned in 1996 after receiving guarantees of safety.

Such brutality kept him in power through war with Iran, defeat in Kuwait, rebellions by northern Kurds and southern Shiite Muslims, international sanctions, plots and conspiracies.

In the end, however, brutality was his undoing. Trusting few except kin, Saddam surrounded himself with sycophants, selected for loyalty rather than intellect and ability.

And when he was forced out in April 2003, he left a country impoverished – despite vast oil wealth – and roiling with long suppressed ethnic and sectarian hatred.

He ended up dragged from a hole by American soldiers in December 2003, disheveled and with his arms in the air.

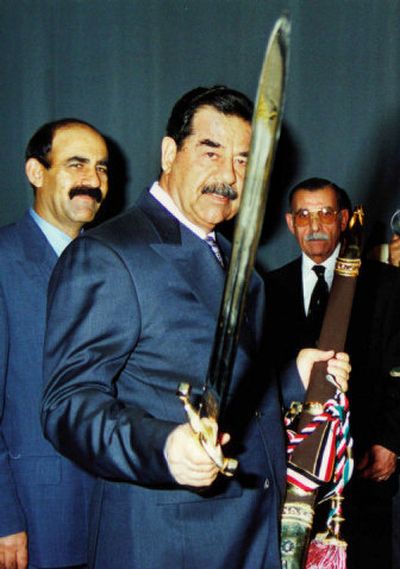

Image and illusion were important tools for Saddam.

He sought to build an image as an all-wise, all-powerful champion of the Arab nation. His model was the great 12th-century warrior Saladin. He promoted the illusion of a powerful Iraq – with the world’s fourth-largest army and weapons of terrible destruction.

Yet it was all hollow. His army crumbled when confronted by the Americans and their allies in Kuwait in 1991.

And in 2003, his capital fell to a single U.S. brigade task force.

Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction proved a bluff to keep the Iranians, the Syrians, the Israelis – and the Americans – at bay.

He squandered vast sums on opulent palaces – a universe from the harsh poverty into which he was born on April 28, 1937, in the village of Ouja near Tikrit. His father died or disappeared before he was born.

The young Saddam ran away as a boy and lived with his maternal uncle, Khairallah Talfah, a stridently anti-British, anti-Semitic man whose daughter, Sajida, would become Saddam’s wife.

Under his uncle’s influence, Saddam joined the Baath Party, a radical, secular Arab nationalist organization, at age 20. A year later, he fled to Egypt after taking part in an attempt to assassinate the country’s ruler, Gen. Abdul-Karim Qassim, and was sentenced to death in absentia.

Saddam returned four years later after Qassim was overthrown by the Baath. But the Baath leadership was itself ousted within eight months and Saddam was imprisoned. He escaped in 1967 and took charge of the underground Baath party’s secret internal security organization.

In July 1968, Baath returned to power under the leadership of Gen. Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, who appointed Saddam, his cousin, as his deputy. Saddam systematically purged key party figures, deported thousands of Shiites of Iranian origin, and supervised the state takeover of Iraq’s oil industry, land reform and modernization.

Al-Bakr decided in 1979 to seek unity with neighboring Syria, whose president would become al-Bakr’s deputy, and Saddam would be marginalized. Saddam forced his cousin to resign – and then purged his rivals. Hundreds in the party and army were executed.

Saddam then turned his attention to the country’s Shiite majority, whose clerical leaders had long opposed his secular policies. Saddam’s fears of a Shiite challenge rose after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini seized power in Shiite-dominated Iran in 1979.

On Sept. 22, 1980, Iraqi troops crossed the Iranian border, launching a war that would last eight years, cost hundreds of thousands of lives on both sides, and devastate Saddam’s plans to transform Iraq into a developed, prosperous country.

After the Iranians counterattacked, Saddam turned to the United States, France and Britain for weapons, which those countries gladly sold him to prevent an outright Iranian victory. They turned a blind eye when Saddam ruthlessly struck against Iraqi Kurds, who lived in the border area and were dealing secretly with the Iranians.

An estimated 5,000 Kurds died in a chemical weapons attack on the town of Halabja in March 1988.

Only two years after making peace with Iran, Saddam invaded Kuwait, whose rulers had refused to forgive Iraq’s war debt and opposed increases in oil prices that Iraq desperately needed to recover from the conflict with Iran.

The United Nations imposed economic sanctions on Iraq, and a U.S.-led coalition attacked. On Iraqi radio on Jan. 17, 1991, Saddam predicted “the mother of all battles.”

But the Iraqis were driven out of Kuwait. The 1991 war triggered uprisings among Iraq’s Shiites, brutally crushed by Saddam, and the Kurds, who carved out a self-ruled area under U.S. and British air cover.

The U.N. sanctions remained in effect until his regime collapsed in 2003, devastating Iraq’s economy and impoverishing a people who had been among the most prosperous in the Middle East.

The Sept. 11 terrorist attack on the United States focused attention on Saddam as a sponsor of terrorism. His refusal to meet U.N. demands for full disclosure of his illegal weapons program provided a justification for war.

An American-led force invaded on March 20, 2003. Within three weeks, Iraq’s army had collapsed. Saddam was captured the following December.