Hagen’s legacy unforgettable

CHICAGO — If Walter Hagen still were around, he probably would toast Tiger Woods for tying him for second on the all-time list with 11 major championships.

Woods eventually will pass Hagen, perhaps even as soon as this week’s PGA Championship at Medinah Country Club.

But he would have to go a long way to keep up with Hagen’s legendary lifestyle. Not that he would want to try.

Hagen’s days are well worth retelling, because he was the Babe Ruth of golf, both on and off the course.

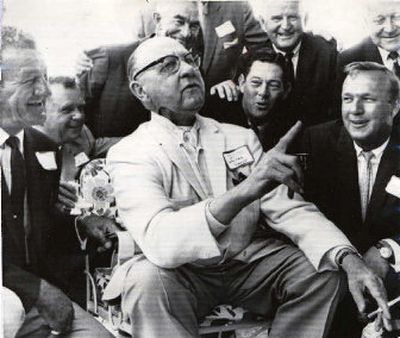

He was a larger-than-life player, dominating as one of the game’s greatest showmen.

The dapper Hagen was as well known for high living, hard drinking and carousing. Naturally, Hagen and Ruth ran together many times in the `20s and `30s, each adding to the other’s nightlife legend.

An associate once said of Hagen, “He broke 11 of the 10 Commandments.”

There’s little denying Hagen’s record as a player. Hagen and Jack Nicklaus are the two biggest winners in PGA Championship history. Each won five titles.

Hagen won his first major — the U.S. Open at Midlothian Country Club in 1914 — at age 21. In 1922, he became the first American to win the British Open, a tournament he won four times.

Hagen never got a true shot at winning the Masters because he was past his prime when the tournament debuted in 1934.

At his peak, he could have walked away with multiple titles at Augusta National.

Some historians argue Hagen should be credited with 16 majors. He won the Western Open five times from 1916 to 1932, when the tournament was considered a major.

In a career that spanned 1912 to 1939, Hagen was a wildly popular figure of sports’ “Golden Era.” Yet Hagen’s record tells only a fraction of his story.

Summing up his lifestyle, Hagen once said, “I don’t want to be a millionaire. I just want to live like one.”

“The Haig” is acknowledged to be the first golfer to earn to earn $1 million, and it is believed, the first to spend $2 million.

“Hagen played in tournaments as though they were cocktail parties,” famed golf journalist Charles Price wrote.

Many times, there wasn’t much time between last call and the opening drive for Hagen. There are numerous stories of Hagen showing up at the course in a limo, wearing the tux from the previous night’s party.

Once an official, upset that Hagen was late, asked if he had been practicing a few shots.

“Nope,” Hagen said. “Having a few.”

Hagen broke many of golf’s conventions. When he played, professionals were treated like second-class citizens. They were routinely denied access to the locker room.

Hagen wouldn’t stand for it.

When he was refused access to the stuffy English clubhouses, he parked himself outside in a Rolls Royce and drank champagne and ate caviar.

The night before the 1914 U.S. Open at Midlothian, Hagen became violently ill after eating lobster for the first time at a Chicago restaurant.

Hagen almost withdrew, but that wasn’t his style. Instead, he went out and shot 68 the next day.

That Open title was just the start. His confidence grew from there. When he arrived at a tournament, his signature line was, “Who’s gonna be second?”

More often than not, Hagen backed up the talk, especially in the PGA Championship.

The tournament was match play during the early years, making it more difficult to survive than the current stroke-play format. Yet Hagen won four straight PGA titles from 1924 through 1927.

Hagen won an estimated 75 titles and participated in more than 3,000 exhibitions, earning as much as $1,000 per round, big money in those days.

Hagen, though, never won a U.S. or British Open that Bobby Jones entered.

As a result, Jones was considered the more accomplished player of that era.

But another top player from that time, Gene Sarazen, said in a Sports Illustrated interview that it would be a mistake to discount what Hagen meant to the game.

“I think Walter Hagen contributed more to golf than any player today or ever,” Sarazen said in 1989. “He took the game all over the world. He popularized it everywhere. Walter was at the head of the class. … Walter should not be forgotten. What golf ought to do is build a monument to that man.”

Instead of a monument, Hagen probably would be just as happy if golf fans drank a scotch in his honor.

When he died in 1969, at 76, his favorite saying was printed on a blue placard at the brunch after his funeral. It read:

“You’re only here for a short visit. Don’t hurry. Don’t worry. And be sure to smell the flowers along the way.”