High-tech hopes for Idaho

Some of Idaho’s sharpest minds and most powerful business leaders met Tuesday in Post Falls to sketch out a $50 million plan to make the state famous for something other than its potatoes.

Computer chips, nanotechnology and biomedical devices are just some of the businesses that could help strengthen Idaho’s economy, as well as provide a reason for the state’s smartest young people to find work at home, according to members of the Governor’s Science and Technology Advisory Council.

But to bring Idaho up to speed, massive changes are needed. Members of this high-powered advisory council – including the presidents of the state’s biggest universities, plus executives from Micron, Qwest and Hewlett Packard – say their time is too valuable to waste on technological baby steps.

“If you’re going to bring this group together you ought to work on something that’s going to make a difference,” said Archie Clemins, a Boise entrepreneur who also happens to have spent much of the 1990s serving as commander of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet.

On Tuesday, the group tweaked a $50 million science and technology initiative, which it hopes to convince state lawmakers to fund during the next legislative session. Although details on the stimulus package won’t be ready for another month, the proposal is expected to include major tax credits for private investment in technology startup companies, an initiative to bring high-speed Internet to the state’s many isolated communities, a $2 million marketing campaign and a $25 million fund to help stimulate the growth of science and technology businesses.

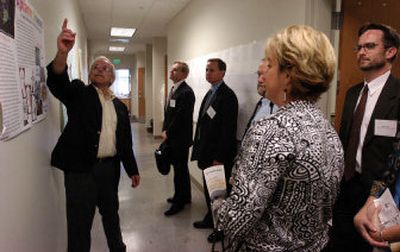

Council members spent their lunch touring the University of Idaho’s Research Park in Post Falls. One of the tech startups at the park, the Center for Advanced Microelectronics and Biomolecular Research, receives about $100,000 in funding each year from the university, but has managed to bring in about $6 million in grants and contracts in the last three years, according to university officials.

The council is also considering the merits of a new Idaho Department of Science and Technology, which would require an annual budget of about $50 million. Council members admit the price tag and Idaho’s squeamishness over large government programs makes such an idea unlikely, but they also point out that they were given marching orders by the governor to come up with “bold and aggressive” ideas.

“The governor’s task was for us to be a think tank and brain trust,” said council chairman John Grossenbacher, director of the Idaho National Laboratory. “That’s what we’re trying to do here.”

A shortage of investment capital and a lack of technology infrastructure were listed by many council members as the main roadblocks for the state.

Major data lines – called “information canals” by some in the tech industry – cross Idaho along the Interstate 90 and 84 corridors, but huge gaps remain in the state for access to high-speed Internet. This ability to quickly transfer information is critical for new businesses, as well as schools, said Robin Woods, president of Alturas Analytics of Moscow. Much of the state south of Moscow and north of Boise has access only to slow telephone lines.

“It’s infrastructure that’s just as important as roads and health care,” Woods said.

A recent state study discussed at Tuesday’s meeting showed that about half the state’s school districts don’t have access to high-speed Internet lines, which are defined as being able to carry 1.5 megabytes of data per second. This contrasts with some Asian countries, such as South Korea, where even the smallest villages are being connected to fiber-optic lines capable of transferring 155 megabytes per second.

Businesses such as biomedical engineering and computer chip design demands such speeds to share huge data files, council members said. Clemins, the retired admiral, said the technology stimulus proposal will float only if legislators understand how such infrastructure could help isolated areas.

“This is to help small-town Idaho survive,” Clemins said.

For all its potential benefits, the high-tech world offers few guarantees and the infrastructure doesn’t come cheap. Jim Schmit, president of Idaho operations for Qwest, said the state might be able to find savings by consolidating demand and moving forward with a large modernization project.

“You would have a significant buying purchase power that industry would respond to,” Schmit said.

The council agreed to support a $50 million tax credit proposal over five years for new technology companies. The idea is to promote investment by providing a 35 percent tax credit for high-tech investment.

About 20 other states have similar tax credits, including Wisconsin, which saw a 65 percent boost in investments following its new tax credit, said Steve Simpson, president of the Boise Angel Alliance. “We have a shortage of investment capital to help entrepreneurs – that’s particularly true with biosciences,” he said.

Idaho’s not completely mired in the dark ages, however. Boise, with 1,213 new patents last year, was recently listed by the Wall Street Journal as the nation’s eighth most inventive city. This puts Boise alongside Austin as the only two cities outside of California in the top 10. Seattle had only 784 patents.

About 70 percent of Idaho’s exports come from the technology industry – mainly computer chips from Boise – according to the Idaho Department of Commerce and Labor. The state also employs about 50,000 technology workers, who earn an average of twice the typical wage for the state.

Woods, who runs a high-tech analytical laboratory in Moscow, said Idaho can’t seem to shake its earthy reputation. Many of her colleagues in the pharmaceutical industry only think of Idaho as “potatoes and fly fishing,” she said, adding that it might be easier to run her lab from San Francisco. “But we like to live here.”