Hand of experience guides Spokane Valley

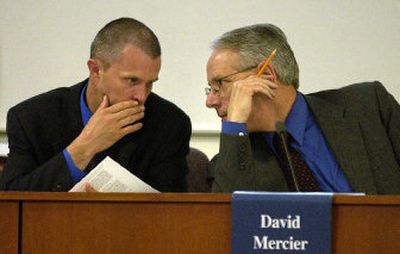

In Spokane Valley, David Mercier is probably the most important man the average person couldn’t pick out of a crowd.

Monday will mark three years since he began serving as the young municipality’s city manager. He likes to steer attention to elected leaders, and he’s known for his measured and often quiet demeanor. But Mercier’s low profile belies his importance as the city’s chief executive. City department heads answer to him. He has a large role in crafting the city’s long-term finances, and he’s advised an inexperienced City Council on long-range planning and other issues that will affect Spokane Valley for decades.

“He brought a lot of experience with him – the rest of us were all newbies,” said Mayor Diana Wilhite.

At his office last week, Mercier proudly slid a paper across his desk with the City Council’s stats so far: 113 resolutions, 183 ordinances and 520 total council actions in just over three years.

In his experience it takes about five years to develop all of the systems and ordinances a new city needs to put in place, and Mercier said Spokane Valley is right on track.

Behind the scenes, Mercier said, he hopes to establish internal policies for Spokane Valley that can be a model for other cities as well. “We’re not trying to achieve the minimum. We’re trying to achieve the state of art,” he said.

As an example, Mercier described the upcoming rewrite of the city’s development code, which he said will be a single easy-to-read volume that other communities may want to use as a template. He also noted presentations given in Millwood and Rockford on Spokane Valley’s code enforcement policies.

His staff includes about 60 people. With many of the city’s services contracted to Spokane County or private companies, that’s less than a tenth the number of employees in Kent, Yakima and other Washington cities of similar size.

“We have high expectations of people in our employ. The workload is very, very significant,” he said.

Their effort hasn’t gone unnoticed by the City Council, which routinely compliments the city staff and city manager. But Mercier’s style isn’t without its critics.

“I would liken him to the man behind the curtain in ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ ” said Debra Alley, who worked briefly in the planning department.

Mercier’s influence could be seen in most city business she witnessed, but “he was not visible. He was not communicative to any of us,” she said.

A clerical assistant to 15 employees and the Planning Commission, Alley said she put in a lot of overtime to make things work.

“It was the largest workload I’ve ever had in my life,” she said.

She left in 2004 because she was offered a job at a community college similar to positions she’d held in the past, she said.

Alley was one of several employees who helped form a union shortly after the city got started.

Employees and city management are still in contract negotiations that began a year ago.

Privately, several current city employees have also expressed concerns about the city’s staffing and the amount of time the city manager spends out of town.

Mercier is active in several state and national professional organizations for city managers. A review of his calendar from 2005 shows he spent about 30 days at various conferences, most of them outside the area and at city expense.

He also was absent from 12 of the city’s 52 council meetings and study sessions last year.

Spending that much time working with professional groups is standard for a city manager, Mercier said. It also benefits Spokane Valley to learn from other cities and to be part of groups that influence state and national policy, he said.

“Spokane Valley does not exist in a vacuum, and it’s very important for city representatives to participate,” Mercier said.

As for the missed council meetings, the mayor said it’s understandable given his busy schedule and his absences haven’t hurt anything.

In the other places he’s worked, opinions of Mercier’s management also vary. But for the most part, past employers hold him in high regard.

“David is a consummate professional and just a decent man to work with,” said George Campbell, an executive with CB Richard Ellis real estate consulting. “You’ve got a good one out there.”

Campbell hired Mercier as the community and economic development director of Old Town, Maine, a municipality in bad shape economically in the early 1980s. There, Mercier helped the town win several federal grants, clean up its downtown and complete other beneficial projects, Campbell said.

Mercier left that position to become town manager of Fairfield, Maine, where he worked for four or five years without incident until the town council made a controversial land-use decision involving development next to a stream.

“City managers work in a politically charged environment,” he said.

After three of the five people on the council were recalled, a new council fired Mercier and the city attorney in 1990.

In a case reaffirmed by the state supreme court, Mercier sued the city and three city councilors for wrongful termination, eventually recovering $230,000 in damages and attorney fees, according to news reports.

Mercier had been looking to move to the Northwest, where he had family. After six years at a Maine state agency, he returned to municipal government as the first city manager of Battle Ground, near Vancouver, Wash.

Leaders in Battle Ground credited Mercier with straightening out the city’s finances, helping it get a federal grant to fix its sewer and crafting development regulations that allowed the city to end an emergency building moratorium and grow 65 percent in the four years he was there.

But some new members of the City Council had mixed feelings about Mercier when they took office shortly after he left in 2001, said Councilwoman Lisa Walters.

“I knew he’d bail simply because some of us disliked his management style,” she said. “Everything was backdoor.”

She contends that he tightly controlled some areas of city business that should have been brought before the council, while leaving other important tasks to his assistant and ignoring personnel problems in the police department.

Mercier said it was a pressing family matter that prompted him to leave Battle Ground and return to Maine. He chose not to talk about it on the record. Back in Maine, he headed an agency that conducts research for the state Legislature under the direction of David Boulter, who also oversaw Mercier’s work years earlier in his previous state government post. Bolter said that in both positions Mercier was a respected and able administrator, particularly in financial matters.

Mercier left after two months because of a worsening health condition that the people who hired him knew about when he started, Boulter said.

He came back to Washington and later began taking consulting jobs through Kenbrio Consulting Inc., a firm he started with his sons.

When Mercier heard the state’s newest city was looking to hire a manager, he drove up from Vancouver and sat in the back of the room during one of the City Council’s first meetings. He was impressed by the city’s leaders and was attracted to the Spokane area, so he applied through a Seattle company the council hired to recruit a city manager.

The council chose Mercier from among 60 applicants, saying then they liked what he had done in Battle Ground as well as his skills as a negotiator and his lengthy résumé in government.

They signed an open-ended contract that outlined a base salary of $115,000 – about the average for Washington cities with more than 50,000 residents.

The contract also provides for a severance package equal to a year’s salary and benefits in the event of Valley disincorporation or dismissal without just cause.

He receives five weeks of paid vacation, some of which he uses to conduct consulting work outside the city, he said.

The agreement contains language releasing him from any obligation to live in the city, and since taking the job Mercier has lived in an apartment in Liberty Lake.

In a 2003 newspaper story, Mercier said he and his wife, Jane, would move to Spokane Valley at the end of that school year. So far that hasn’t happened, and he said it’s still uncertain when he will move to Spokane Valley permanently.

Jane Mercier is special education director for the Battle Ground School District. Her position, like his, is unique and relocating has yet to work out, Dave Mercier said.

The mayor said Mercier’s commute hasn’t been a problem, and judging by their public statements, other members of the City Council also seem happy to have Mercier at the helm.

“I don’t have a home-grown picture of what the Valley should look like ‘X’ number of years in the future,” said Mercier, adding that it will be the elected leaders who determine what the young city becomes.

He’s optimistic about the future, though, and said he has enjoyed his job so far.

“It’s been just as stimulating as it has been demanding,” he said.