Color correcting

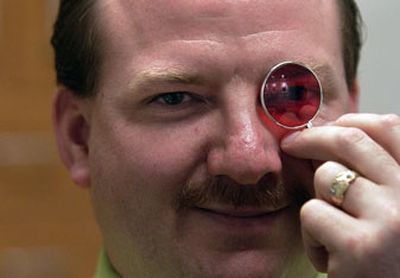

After 57 years of coping with colorblindness, Mark Brazelton’s not inclined to fix it now.

He’s not a cop. Never could be a pilot.

And the Spokane Valley man found a way to avoid fashion disasters long ago.

“I wear black all the time,” said the employee of Itron Inc. “When I used to have to wear a tie, I let my wife pick it out.”

Still, it’s intriguing for Brazelton and others to learn that correcting flawed color vision can be as simple as slipping in a contact lens.

Larry Breazeal, a Spokane Valley optometrist, is among a small group of professionals who hand-tint lenses to help clients compensate for color deficiencies. Using the same technology that makes brown eyes blue or green eyes even more emerald, Breazeal can craft magenta, pink, orange or green lenses to offset the effects of colorblindness.

“It doesn’t get you to see color,” Breazeal cautions. “It gets you to see the contrast.”

For the handful of clients who’ve ordered the contacts in recent years, that’s good enough, Breazeal said.

The group has included several police officers and a pilot, professionals whose jobs require them to pass color vision tests to be hired. Another client was the owner of a North Idaho paint store.

“He was embarrassed,” Breazeal said.

They were all male, which is no surprise. Generally, about 8 percent of men are colorblind, compared with less than 1 percent of women, the optometrist said. A genetic impairment, the marker for colorblindness is carried on the X chromosome and usually passed from a woman to her sons.

The condition, sometimes classified as a disability, is a disorder involving light-sensitive cells in the retina of the eye. There are two kinds of cells on a normal retina: “rods” that are active in low light and “cones,” which function in daylight.

In people who are colorblind, the cones don’t function properly, or, sometimes, at all. The most common disorder is red-green colorblindness, in which sufferers have difficulty distinguishing shades of red, green and brown.

“They learn about it when they’re little,” Breazeal said. “The teacher says, ‘Color a tree,’ and he colors the leaves red.”

That was the case with Brazelton, who learned he was colorblind at about age 6, when he couldn’t discern certain shades of crayons.

Like most colorblind boys, he learned to compensate, judging shades by their intensity, instead of their hue.

“I can tell a blue car from a red car from a green car,” he said.

And he can tell a red light from a green light at a traffic signal, but only because the red light on top is darker than the green light on bottom, which is bright.

“The only time it’s a problem is when I’m driving somewhere where they have their signals sideways,” Brazelton said.

People whose professional duties require specific color vision have more trouble if their vision remains uncorrected, Breazeal said. A police officer might not be able to see red blood on green leaves, he noted. Or a pilot might not be able to recognize one landing light from another.

Some government and law enforcement agencies allow employees to correct color vision with glasses or contacts, just as they permit workers to use other aids. The Federal Aviation Administration requires colorblind applicants to pass one of several standardized tests, which can range in difficulty.

Most potential employees simply ask an optometrist such as Breazeal to test and verify their vision.

Those who want corrective lenses can opt for what are called “X-Chrome” glasses or contacts, Breazeal said. One client walked away with a pair of glasses that sported one pink lens and one magenta lens. Color-correcting contacts cost the same as any colored lenses: about $120 for six months’ wear, Breazeal said.

People who opt for correction are usually happy with the results, the optometrist said. Suddenly, a hunter can track a deer more accurately. A police officer will be more confident about the color of the fleeing vehicle.

For men like Brazelton, however, colorblindness has become nothing more than a personal quirk.

“Would I fix it? Probably not,” he said. “It’s just not enough of a problem for me.”

Reach reporter JoNel Aleccia at (208) 765-7124 or by e-mail at jonela@spokesman.com.