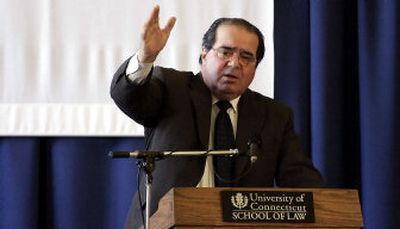

Scalia more outspoken than justices in past

WASHINGTON – Justice Antonin Scalia is at it again.

“For Pete’s sake, if you can’t trust your Supreme Court justice more than that, get a life!” he said Wednesday, replying to an audience member at the University of Connecticut who asked about Scalia’s refusal last year to sit out a case involving his hunting partner, Vice President Cheney.

Scalia had similar advice to a student in Switzerland who asked last month about the Supreme Court’s ruling for George W. Bush during the 2000 election. “Oh, God. Get over it,” he said.

And, on March 27, he answered a Boston Herald reporter’s question about criticism of his conservative religious beliefs by putting his fingertips under his chin and flipping them dismissively outward. “That’s Sicilian,” the high court’s first Italian-American explained, triggering a controversy that would spill over to cable TV and prompt a testy letter to the editor of the Herald from Scalia himself.

One of the most conservative – and cerebral – of the nine justices, Scalia, 70, has never shied from verbal warfare.

But as he completes his second decade on the court, Scalia, often known by his nickname, Nino, seems less inhibited than ever, speaking frequently off-the-cuff, in a crowd-pleasing voice quite unlike that of the legal academy to which he once belonged.

It is the voice of a conservative populist: combative, humorous, and sharply critical of the media and of the legal establishment atop which he sits. That includes the Supreme Court, from whose rulings in favor of gay rights and against the juvenile death penalty he dissented vigorously.

To some, Scalia’s conduct shows a lack of judicial temperament – and hurts the court. “It’s sad as much as anything else,” said Dennis J. Hutchinson, a former law clerk to two justices who teaches Supreme Court history at the University of Chicago. “It suggests to me a frustration with his colleagues and the left-wing kulturkampf in the academy, and it just does not add to the dignity of the office.”

But Scalia’s supporters say it is simply Nino being Nino, offering the public a playful taste of his unvarnished thinking, which they call healthy for the court.

Scalia’s outspokenness is facilitated by modern judicial ethics laws that leave it up to members of the court to decide when their comments create an appearance of impropriety.

On the current court, Justice David H. Souter almost never speaks publicly, and Justice John Paul Stevens rarely does. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Samuel A. Alito are still settling in.

But the old taboo on speeches and interviews has broken down. Most justices speak out relatively often, trying to avoid comment on pending cases or issues that might come before the court. Justice Stephen G. Breyer, one of the court’s liberal members, engaged in a recent series of interviews and speeches, many televised, on his new book on constitutional interpretation – which was a riposte to an earlier one by Scalia.

What is different about Scalia is his folksiness and his bluntness in response to questions. In 2004 he had to recuse himself from a case involving the constitutionality of the phrase “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance because he publicly commented on the issue while it was pending.

There were calls for his recusal from a case on military commissions after reports of his March 8 meeting at the University of Friburg in Switzerland, where he told the audience that it was “crazy” to suggest that terror suspects get a “full jury trial.” Scalia participated in the case.

The recusal issue overshadowed the rest of Scalia’s hourlong comments, in which he called constitutional courts in Europe “the mullahs of the West” because they try to decide moral issues, rapped Europe’s “anti-American left-wing press” and noted, regarding the impeachment of President Clinton, that “we really don’t like our presidents fooling around in the Oval Office. We’re funny that way.”