Drawn straight from their hearts

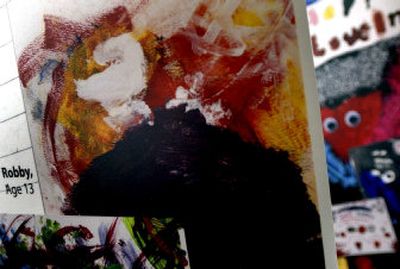

To tell the truth, Robby Kelley doesn’t remember what he meant when he splashed bright paint across a white page and then topped it with a splotch of black.

He knows it was a painting project last summer for kids with – and without – mental illness.

But the 14-year-old Bonners Ferry boy has been too busy with school and family and hobbies – basketball, video games – to dwell on the ways a diagnosis makes him different.

Score one for “Art from the Heart.”

Robby’s abstract artwork was among pieces submitted by about 300 children across Idaho as part of a statewide program aimed at decreasing stigma about severe emotional disorders, organizers said.

The point of the program – which produced a traveling art exhibit titled “The World Through Our Eyes” – is the very normalcy of youngsters like Robby. Diagnosed at age 7, Robby takes medication to control attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and some symptoms of bipolar disorder.

“Robby is basically just a typical kid,” said his mother, Debbie Kelley.

Emphasizing the commonality of all children was the goal of the effort co-sponsored by the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare and the Idaho Federation of Families.

“The main thing is when we look at stigma, when people are stigmatized, they are labeled and isolated,” said Chandra Story, a spokeswoman for the health and welfare department.

Creating a 42-by-18-foot display crowded with paintings and poetry of children with mental disorders and those without was a way to integrate the experiences of everyone, Story said.

“The display does exactly what anti-stigma does,” she said.

“The World Through Our Eyes” debuted in January at the state capitol in Boise. Since then, the display has traveled north, leaving awareness in its wake. In Idaho, more than 17,000 children are affected by mental health disorders, Story said.

“We’ve had phenomenal experiences happen,” said Cynthia McCurdy of Rexburg, who was recently named Idaho’s Mother of the Year. She helped bring the display to her community.

“There was over a four-hour wait of people in line,” McCurdy said. “More than 5,000 people – college kids, professors, community members came.”

The exhibit helped spark positive responses, including an offer by a community member to sponsor spaces in sports programs and other activities for emotionally disturbed kids.

McCurdy has been a vocal advocate for the rights of mentally ill children since the birth of her daughter, Karissa, 14. She believes awareness starts in the family and extends through the larger community.

Too few people understand the challenges faced by children with emotional disturbances – and those confronted by their families. It’s often a fight to fit in at school, in social settings and in society at large.

“It’s important to decrease stigma because none of us likes labels,” she said. “Most kids can overcome mental illness and even if they don’t, it’s OK being who they are.”

McCurdy said she was moved by the artwork, including many that illustrate the difficulties some children face.

“A lot of these kids have dark lives, they perceive it as being dark,” she said.

A drawing by Karissa is included in the show.

“She drew a heart where her lips are because she told me, ‘I always want to speak kind words about others,’ ” McCurdy said. “She drew colors where her heart is and she said, ‘These are my feelings.’ ”

For children with mental and emotional challenges, artwork can be a powerful tool, said Joe Fleck, a state mental health clinician in Bonners Ferry. He praised Gov. Dirk Kempthorne’s work to provide targeted local services for children with mental illness. Part of that plan requires the kind of community education and awareness exemplified by the artwork of Robby Kelley and the others.

“They don’t always have a voice,” Fleck said. “This creates that voice.”