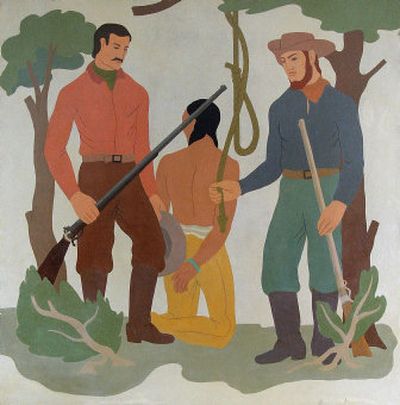

Lynching murals in courthouse spur debate

BOISE – For 66 years, two murals depicting the lynching of an American Indian have hung in a now-abandoned county courthouse in Idaho’s capital, monuments to prevailing attitudes that once dominated the West but today have become uncomfortable reminders of America’s expansion to the Pacific Ocean.

Starting in 2008, the Idaho Legislature plans to meet in the courthouse as its century-old Statehouse undergoes a $115 million revamp.

Historic preservationists say they’ll fight attempts to remove the murals, products of the Works Progress Administration Artists Project, a federal program that employed jobless artists during the Depression. The 1940 works are part of the building, some historians say.

Still, Indian leaders and many lawmakers say turning the old Ada County Courthouse into Idaho’s most public building, even temporarily, will force to state to confront the future of the murals, which one local judge in the 1990s found so offensive he draped an American flag over them. Race relations in Idaho, once home to the white supremacist Aryan Nations group, are a sore spot.

“It’s a perfect opportunity to educate the state of Idaho and its citizens on the kind of biases that Native people endured,” said Chief Allan, chairman of the Coeur d’Alene Indian Tribe in North Idaho. “If we could sit down with the historical society, and have a sit-down with them, we could help make sure this won’t happen again in the future.”

Some Shoshone-Bannock tribe members, whose traditional territory included Ada County, say the murals make many Indians uncomfortable.

“As an individual member of the Shoshone-Bannock tribe, those murals do impact people and their feelings,” said Claudeo Broncho, of Fort Hall. “They should be painted over.”

A week ago, the Legislature approved $5.9 million to begin moving its offices to the Ada County Courthouse, which the state bought five years ago after a new courthouse was built several blocks to the southeast. The 2008 and 2009 sessions will be conducted there while an additional 100,000 square feet of space is added to the existing Capitol. It will be completed by 2010.

Arthur Hart, director emeritus of the Idaho State Historical Society and author of a 2005 book on the courthouse, says removing the murals would detract from their historical significance. They’re among 26 separate paintings that were painted in Southern California, then shipped to Boise to be mounted in the courthouse in 1940.

While the lynching murals don’t represent a known event in Ada County, they’re representative of what might have occurred in Idaho and the rest of the West as settlers descended on the region, Hart said.

For instance, Qualchan, a Palouse Indian, was hanged by Col. George Wright near the Idaho-Washington border along a tributary of the Spokane River at the conclusion of the Coeur d’Alene War of 1858. And as many as 400 Shoshone Indians were killed by the U.S. Army Cavalry along the Bear River near present-day Preston in 1863.

“I can understand it’s not politically correct anymore,” Hart said of the paintings, which for eight years were covered by an American flag at the order of District Judge Gerald Schroeder, now the Idaho Supreme Court chief justice. “But the murals are an integral part of the building.”

Tim Mason, who oversees the Ada County Courthouse as administrator of Idaho’s public works, says pulling them from the staircase wall – they’re attached with a six-decade-old adhesive – would be costly and time-consuming.

Nonetheless, some lawmakers say removal to a local museum might be best, because everybody entering the courthouse would be forced to walk past the murals as they climb steps to where the House and Senate will meet. This year, leaders from Idaho’s five American Indian tribes spent much of February inside the Capitol, campaigning on sovereignty issues including gas taxes and tribal gaming rights.

“All of the murals need to be evaluated, both for their appropriateness and their artistic value. I find those offensive,” said Sen. Joe Stegner, R-Lewiston, whose district includes the Nez Perce Indian Reservation.

Sen. Mike Jorgenson, R-Hayden Lake and the Senate Indian Affairs Committee chairman, said Idaho should be bold in addressing concerns of minorities. The late Richard Butler operated his Aryan Nations headquarters near Hayden Lake for three decades until his death in 2004. Jorgenson said his constituents know well the power of racist symbols or representations – be they swastikas or pictures of Indians being hanged by armed whites.

“We have rapidly improving relations with the tribes,” he said. “It’s important that this be dealt with.”