A mother’s story

WANTAGE, N.J. – Thirty years ago, she was a household name.

Like Vietnam and Watergate, Karen Ann Quinlan became shorthand for a history-changing international discussion.

In her case, it was about whether families, rather than doctors, could decide to withhold medical treatment from loved ones, even if death would be the consequence.

After losing consciousness and oxygen to her brain in April 1975, the 21-year-old suffered irreversible brain damage. Her parents’ legal efforts to remove her respirator resulted in a precedent-setting state Supreme Court case a year later, although Quinlan continued to survive in a persistent vegetative state until June 1985.

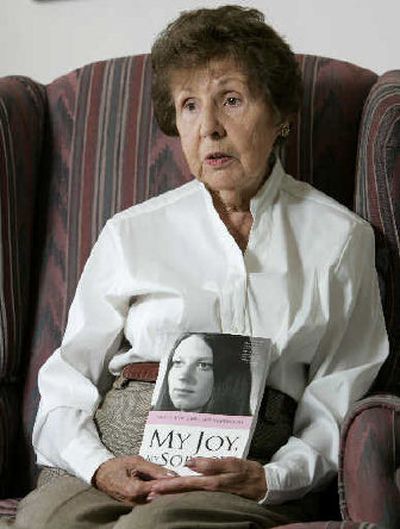

Now her mother, Julia, 78, has written a memoir about how she and late husband, Joseph, became accidental pioneers for patients’ rights and hospice care, “My Joy, My Sorrow: Karen Ann’s Mother Remembers” (Saint Anthony Messenger Press, 159 pages, $14.95).

Not a professional writer, Julia Quinlan spent several months researching how to write a query letter to publishers and then fielding polite rejection letters. Doubleday, which had published “Karen Ann: The Quinlans Tell Their Story,” the 1977 book the couple co-wrote with journalist Phyllis Battelle, also declined.

Then she tried St. Anthony Messenger Press, which primarily publishes books on theology and social justice. Editor Mary Hackett said it was the first time the Cincinnati-based company had considered a memoir, which landed on her desk as the legal battle over Terri Schiavo’s end-of-life wishes was raging.

“The idea of the right to die was getting a lot of talk, and (Quinlan’s manuscript) just happened to arrive at that time,” Hackett said. “Everyone was drawn into the story, which was really about a spiritual journey.”

Quinlan insists, though, that writing her memoir had nothing to do with the Schiavo case.

In its spareness, “My Joy, My Sorrow” underscores the contrast between the Quinlan’s case and that of Schiavo.

Schiavo’s parents, until their daughter’s death last March after 15 years in a persistent vegetative state, sought media attention; the Quinlans shunned it. The enduring image of Schiavo is a brain-damaged woman staring from a hospital bed; that of Karen Ann Quinlan remains a studio photograph from her high school yearbook.

It was the night of April 14, 1975, when 21-year-old Karen, the eldest of three Quinlan children, went out for drinks with friends. But she had also taken the drug Valium and passed out.

A friend helped her home to the apartment she shared with another young woman, laying her down on her back. Quinlan said her daughter apparently aspirated vomit into her windpipe, cutting off oxygen to her brain for at least 10 minutes before receiving emergency treatment.

Apart from one very fleeting moment a few days after Karen was hospitalized, there was never any sense that Karen recognized her family or was aware of her surroundings, Quinlan said.

By late May, doctors concluded that Karen would never recover. The family decided it was time to remove her from the respirator, knowing it would likely mean death.

“You pray for miracles,” Quinlan said. “Life is special. You should do everything possible to extend a person’s life, but there is a time for each of us to die.”

They had the support of their parish priest, the Rev. Tom Trapasso, now a retired monsignor.

“They didn’t want her to die but to return to a natural state,” Trapasso recalled recently. While he opposes euthanasia, and the notion of a “right to die” that would include suicide, he said, “We have a right to decide how we should be treated.”

The Quinlans told Karen’s doctors of their wishes, and Joseph Quinlan signed documents releasing them from legal liability, but the hospital’s lawyers balked. In September, lawyer Paul Armstrong filed a lawsuit on the family’s behalf.

“There was no law in the area,” said Armstrong, now a state Superior Court judge. “We had some apprehensions. We knew it would be a landmark case.”

While popular opinion supported the Quinlans’ request, the judge did not. An appeal to the New Jersey Supreme Court was successful in March 1976, with a 7-0 ruling that the family’s right to determine Karen’s medical treatment exceeded that of the state.

About six weeks later, doctors began to wean Karen from the respirator, and the family kept an around-the-clock vigil. But perhaps due to her youth, lifelong athleticism and independent spirit, she continued to breathe on her own for another nine years.

On June 11, 1985, Karen died of pneumonia in a nursing home.

“Today, we question our doctors about our rights. We have the advance directives and living wills that I hope young people have filled out,” Julia Quinlan said. “That’s the purpose that Karen’s life served and is still serving.”