Jenks comes out ahead at last

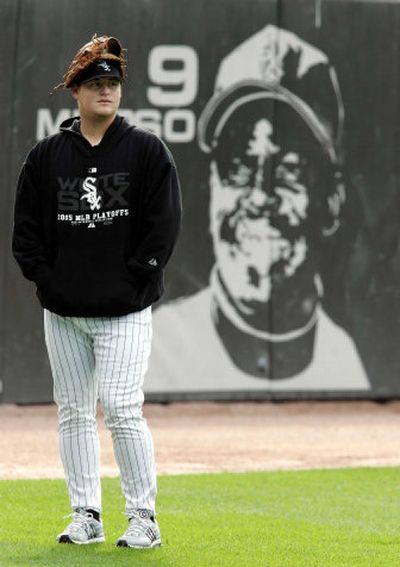

The story came out and it told the tale of Bobby Jenks, the 6-foot-3, 270-pound waste of talent from the backwoods of Idaho.

Less than three years later, with the 24-year-old former Spirit Lake resident closing games for the American League champion Chicago White Sox, that all sounds a little ridiculous.

It was a Greek tragedy hijacked by Disney producers. The kid with all this natural ability, throwing the ball 102 mph but failing because he couldn’t keep his head screwed on. Now, after a little more than three months in the major leagues, Jenks will close games in the World Series.

This wild ride started with Jenks’ rise to prominence as a baseball player in North Idaho, where he played his sophomore year at Lakeland High School for Ken Busch.

Jenks was the Hawks’ No. 2 starter and third baseman in 1998, batting .372 and going 4-2 with a 1.89 ERA on the mound, striking out 55 in 37 innings.

“I had heard some things during the school year about this kid who had just moved into the area,” Busch said. “It was all pretty much hearsay, but he was the real deal. As we went through practices, we saw that he could play.”

That would be Jenks’ only year of high school baseball.

Busch said that Lakeland had trouble getting him eligible, and he could compete that year only because a teacher found his grades from a previous school, which allowed him to play.

The next year, the school split in half, and Jenks attended Timberlake – where he was never eligible for anything.

“He would tell me, ‘When I go to the other school, I’m going to go play football, too,’ ” Busch said. “It’s got to be frustrating not to accomplish the things he wanted to do. We knew he struggled in the classroom, and I think he has some learning difficulties and I think he got frustrated.”

But that frustration didn’t last in the summer, because he could play. Kim Rogstad, who stays in contact with Jenks, coached him when he was 15 years old before Jenks moved up to American Legion.

“The ball exploded out of his hand,” Rogstad said. “Kids at that age were throwing pretty hard, but he was at another level. He just needed to come up with a changeup. Back then, he could just blow all the kids away.”

Jenks’ arm helped make a name for himself regionally, as he made a Roberto Alomar all-star team for the Pacific Northwest. But he could not afford to play in the tournament, held in Puerto Rico.

“He didn’t have a lot growing up,” Rogstad said. “He was kind of a poor kid.”

His senior year, Jenks dropped out of Timberlake, and transferred to Inglemoor High School in Kenmore, Wash., living with Mark Potoshnik, who worked at the Northwest Baseball Academy in Lynnwood. Jenks never played at Inglemoor, but graduated in 2000.

Potoshnik displayed Jenks’ arm for scouts, and legend has it that his first pitch at one went 6 feet over the catcher’s head, nearly hitting a San Diego Padres scout.

Wildness and all, the Angels drafted him in the fifth round of the 2000 amateur draft, and it seemed like all was well for Jenks. He was going to play professional baseball – his dream – and would get paid to do it.

Then the article came out.

It was June 2003, and Jenks was pitching in Double-A with the Arkansas Travelers. ESPN the Magazine portrayed this massive human being with a magical arm, and how he was blowing it all through drinking and recklessness.

In one instance, the article detailed an occurrence of self-mutilation, when a drunken Jenks burned himself with a lighter. Another time, Jenks earned himself a demotion to Class A when he argued with a manager over Jenks’ desire to bring beer on the bus. Most of the information from the article came from an ex-agent, Matt Soshnick, who claimed Jenks referred to him by an anti-Semitic nickname, which Jenks denies.

“Imagine being in the top five at the world at what you do, and your demons are so terrible that your ability is dwarfed,” Soshnick told the magazine. “That’s Bobby Jenks. The worst thing that could happen is if he gets to the big leagues, he’ll free fall. He can’t handle success.”

Rogstad said he was interviewed for the article, and had nothing but good things to say about Jenks, but none of his quotes made it in the magazine.

“He’s just a real easy kid to get along with,” Rogstad said. “He never caused me any trouble. Coaches used to ask me his strong points. Everyone’s impressed with his arm, but his strongest point is that he likes to play the game. (ESPN) talked to me and called a couple of times, but didn’t seem to be interested in my opinion of it.”

Rogstad feels a little guilt that he never reached out to Jenks at that time.

“I probably made a mistake by not getting a hold of him,” Rogstad said. “What do you do? You’ve got professional people who are supposed to be watching him, I didn’t know if I should say something. I’ll never do it that way again, but I’m sure I’ll never have the chance.”

Busch, who had lost contact with Jenks when he left Idaho, was taken aback at the talent he had and the depth of the problems Jenks was experiencing.

“I was surprised he was throwing 100 (mph) now, and I was surprised to hear about his background,” Busch said. “I didn’t really know him personally that well. It was sad to hear about how tough it was. I’m just glad. You hear about kids who are great athletes who never get a chance.”

The White Sox did not respond to an interview request for Jenks made early this week, but he has talked about his earlier days in other interviews.

“I don’t think I did anything out of character from what any other 21-year-old would have done,” Jenks told the Seattle Times. “Being a young kid and doing some things, I mean, everyone’s gone through it. I was just under a bigger magnifying glass. I didn’t go through the college scene at all. So everything I did would have been my college years early on.”

In the minors, he was used as a starter, and the strain of throwing so hard for so long caught up to him.

During the 2003 and 2004 seasons, he went on the disabled list three times with elbow injuries. Finally, last year, he underwent surgery to insert a permanent screw in his elbow. His 2004 season included only three Triple-A starts and an 8.05 ERA. The Angels gave up on him and put him on waivers.

Chicago claimed him off waivers and signed him for the 2005 season.

Jenks saved 19 of 21 games with the Double-A Birmingham Barons, striking out 48 batters in 41 innings. On July 5, the White Sox called him up to the big leagues.

After he was lit up in his second outing, Jenks rebounded to allow one earned run in his next 121/3 innings as a setup man and middle reliever. He saved the White Sox’s final two games, including the American League Central clincher, finishing the season with six saves in eight attempts, a 2.75 ERA and 50 strikeouts in 391/3 innings.

He was better in the postseason in front of a national audience, firing his triple-digit fastball and a slider that would buckle a parking meter.

In Game 2 of the American League divisional series, Jenks inherited a 5-4 lead in the eighth inning. He finished off the Red Sox, throwing two shutout innings.

After the game, reporters asked Chicago manager Ozzie Guillen why he left Jenks in for two innings.

“Why was he in for two innings? Because he was my best pitcher,” Guillen said. “I wanted my best pitcher against their best hitters. He got the job done, didn’t he?”

Two days later, he closed the series clincher in Fenway Park.

For those who coached him in Spirit Lake, it has been amazing to watch this kid’s surge onto the national baseball consciousness.

“I’m so happy for him,” said Rogstad, who visited Jenks when he pitched at Safeco Field. “I know how bad he wanted it and wants it. He’s proven everybody wrong, all the naysayers. I always had confidence in him.”

Jenks is married with two children, which he credits for settling him down.

“I knew in my heart that once I got the opportunity, I wasn’t going to let it pass by,” Jenks told the Chicago Tribune.

He’s only been in the big leagues for three months, and he has a long way to go to prove that this is a story of permanent, not temporary, redemption.

The script has a lot left to be written.

Now, finally, it appears that Jenks is holding the pen.