Flawed murals” future unclear after 65 years

BOISE – Zella Strickland, a courtroom artist for Idaho television stations, had to fight the urge to pull out her paintbrush every time she walked past the 26 Depression-era murals surrounding the main staircase at the old Ada County Courthouse.

“I would have loosened them up, and had them moving, breathing,” said Strickland. “I’d have put more life in them.”

Since their unveiling in June 1940, the murals – products of the Works Progress Administration Artists Project, a federal program to employ jobless artists during the Great Depression – have drawn similar fire.

Even before the images were finished, the first artist pulled out of the project.

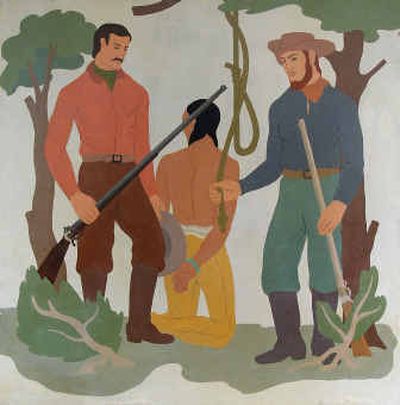

When completed, they were hung in the wrong order. One woman is depicted with two right arms. A stagecoach isn’t connected to the horses supposedly pulling it. Two murals depicting the lynching of an American Indian were ordered concealed by a judge who found them offensive.

“It was like a doomed series from the beginning,” said Ilene Fort, curator of American art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California and an expert on WPA murals, after looking at photos.

Sixty-five years after the murals were installed, historic preservationists, state officials and politicians are considering what to do with them now that the courthouse has been abandoned.

In 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt started the WPA, which eventually spent $11 billion and employed more than 8.5 million people on more than 1.4 million public works projects. The art project employed 5,000 artists who produced a quarter-million works of art in courthouses, post offices and other public buildings.

Much of the art had “social realist” themes, some portraying idealized workers wrenching civilization from the American wilderness.

The artists “thought it should be comprehensible to the individual viewer,” said James Todd, professor emeritus of art and humanities at the University of Montana in Missoula who taught classes on WPA art.

Well-known artists including Jackson Pollock and Willem deKooning participated in the federal program. Another was Ivan Bartlett, the final designer for the Ada County murals, but they were eventually painted by as many as two dozen lesser artists in studios in Los Angeles.

“Artistically, if they were my students, I’d give them a C,” said Arthur Hart, director emeritus of the Idaho State Historical Society.

It was supposed to have worked out differently.

Created by Fletcher Martin, a nationally known artist, the murals were to have included scenes from Idaho history, accompanied by legends explaining their significance.

According to period newspaper accounts, however, Martin withdrew from the project in part because he had more lucrative contracts to paint portraits of wealthy Boise residents.

Bartlett stepped in and redesigned the work, eventually switching to oil-on-canvas from what was likely meant to have been a petrachrome mosaic, in which colored aggregate and mortar form the image. The result falls flat, said Vince Michael, an associate professor of art history at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“They’re definitely the B-list,” said Michael, after reviewing photos. “That’s unusual. Generally, because you were dealing with the Depression era, the government could get high quality stuff for a low price.”

Criticism started almost immediately.

“It seems to me in terribly bad taste to litter up wall spaces that were architecturally fine,” wrote Boise resident Fred F. Brown in a July 1940 letter to the Idaho Statesman.

Six decades later, the controversy continues.

In two murals, an Indian wearing garb atypical for Idaho tribes is accosted by two white men, then lynched by two others. There’s no specific event in Idaho in which that happened, said Hart, who’s writing a local history that includes a mural chapter.

Gerald Schroeder, the Idaho Supreme Court’s chief justice, ordered Idaho and U.S. flags draped over the images.

“They appeared to be a lynching,” Schroeder said. “It was my view that would be offensive, and rightfully offensive, to some people.”

The building has been empty since 2002. It now is owned by the state, which had planned to use it for office space. But Idaho legislators this year failed to agree on whether to renovate it or demolish it, and a decision has been delayed at least another year.

Meanwhile, peeling and water-damaged murals hang in the gloom. Tim Mason, who oversees state buildings, says preservationists have time to address their future.

Removing the canvas from the walls for display elsewhere – they’re attached with a mixture of white lead paste, linseed oil, varnish and turpentine – would be costly though not impossible.

Preservationists including Charles Hummel, son of one of the architects who designed the 1939 courthouse, say they should stay put.

“The murals are an integral part of the building,” Hummel said. “They’re not as bad as one would think they are.”