Idaho urges more tests on BNSF refueling depot

For railroads, speed equals profit.

Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway Co. says a Coeur d’Alene judge’s decision that has kept its Idaho refueling depot closed for the past two months has cost nearly $19 million in lost shipments and repair costs.

BNSF returned to a Kootenai County courtroom Monday to argue the depot is ready to be reopened and that further delays would violate its federal right to conduct business across state lines.

But the state of Idaho said protecting the region’s drinking water from more fuel spills trumps any concerns over restrictions of interstate commerce. Two more weeks of testing and analysis are needed before the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality could agree to the depot resuming operations, according to testimony from Gary Stevens, an agency hydrogeologist.

“It’s a sole-source aquifer. We’re very concerned to minimize or eliminate impacts to the aquifer,” Stevens said Monday, the second day of hearings to determine the fate of the depot.

The hearing ended short of an agreement or a judge’s orders. Both sides asked for an additional week to negotiate an agreement outside of court.

Five hours of testimony Monday revealed considerable disagreements remaining between the railroad and Idaho regulators. The DEQ believes leaks occurred in both liners beneath the depot’s main refueling platform. BNSF experts say oily dirt and tainted water found below the liners could be from lubricants used to drill wells to investigate the problems, which were discovered Feb. 14.

The state also wants more proof that the aquifer is not threatened by several small holes that remain in the liners below the refueling platform, the fuel storage tank area and the site where fuel is unloaded from rail cars. In hearings Thursday, experts hired by BNSF variously described the holes as the thickness of a pencil lead or a 16-penny nail. On Monday, an attorney for BNSF characterized the holes as “pinpricks” and “microholes.”

Stevens, the state hydrogeologist, said more testing is needed. “There are acknowledged holes in these liners. … We need to have a better understanding of the leak rates.”

Before the depot opened Sept. 1 the state had an agreement with BNSF to regularly inspect the depot and test groundwater monitoring wells. Now that extensive repairs have been made to fix problems at the depot, more rigorous monitoring is needed, Stevens said. Although the railroad has instituted many of the changes on its own, including applying five layers of sealants to cracks found across the concrete refueling platform, the state wants more than just a gentleman’s agreement for cleaner operations and increased access at the facility.

BNSF attorney Rusty Robnett suggested the depot was being singled out and that other businesses atop the aquifer, including truck stops, are not required to meet the same standards. “They have a right to be treated like anyone else,” Robnett said.

Since the depot was shuttered at the end of February, BNSF has noticed a 6 percent decrease in the “velocity,” or operating efficiency of its locomotives, according to testimony from depot superintendent Maxine Timberman. The loss is the equivalent of at least seven trains per day and about $7 million in lost shipping revenue over two months.

BNSF’s depot near Hauser is the fastest in the Northwest and the only facility where locomotives can pull through the fuel station without uncoupling their cars, Timberman said. In Hauser, locomotives can take on fuel and have their cabs serviced – including toilets cleaned – in 30 minutes. The same task takes up to five hours in the congested Seattle-Tacoma railyards.

Fewer trains on the tracks mean more trucks on the highway, Timberman said. Tractor-trailer rigs burn more diesel, create more air pollution and operate at a higher risk of traffic deaths and fuel spills, she said. A typical train, for instance, hauls the equivalent of 360 semitruck loads of goods. That could mean enough grain to bake 30 million loaves of bread or enough coal to power 90,000 homes for a year from just one train.

At one point during testimony, BNSF attorney Rob Jenkins referenced a fact sheet titled “Railroads: Building a Cleaner Environment,” which is published by the trade group Association of American Railroads. Depot opponents seated in the courtroom could not stifle their laughter when Jenkins read the title of the paper.

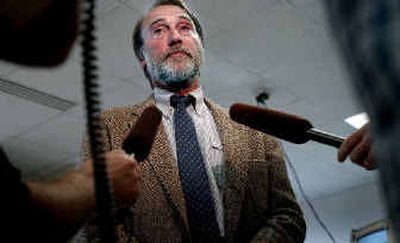

BNSF testimony focused on the costs and national impacts of the closure. Curt Fransen, deputy Idaho attorney general, said the state was only concerned with the Hauser depot and the drinking water 160 feet below. Even if the delays are hurting business, the railroad agreed to build and operate a refueling depot that would protect the aquifer, Fransen argued. “All of these repairs and upgrades are basically designed to do what BNSF agreed to do in the first place.”

Although the railroad said the closure has resulted in nearly $19 million in losses, Fransen tried to balance the figure by pointing to BNSF’s latest earnings report. Last week, the railroad reported a record first-quarter income boost of 18 percent and freight revenues jumping $451 million in the first three months of the year.