Black White

Well over a century after it was abolished, slavery lingers in the American psyche. Each generation seems compelled to confront the institution anew in search of modern understandings.

The latest turn in the national conversation is toward a more intimate look into the lives of slaves – led by a novel that revisits Mark Twain’s classic and racially charged tale, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

“My Jim” is the first-person story of Sadie, the wife of Huck’s enslaved traveling companion. Author Nancy Rawles reimagines Jim as more than a runaway drifting down the Mississippi River with a delinquent youth, more than the gullible victim and moral father figure to Huck that Twain portrays.

Rawles considers the familiar tale from the perspective of the family Jim left behind – like the shattered families of many slaves.

“This was an opportunity to really bring out the individuals who lived this history, to get away from thinking about them en masse and get into the personal stories,” says Rawles, whose novel already is being taught in a handful of high school classrooms alongside Twain’s 1885 saga.

She got the idea for her critically praised story from a few pages in “Huckleberry Finn” that detail Jim’s longing for his wife and children – and for freedom.

Over the years, Twain’s dark humor has challenged – and turned off – students and parents. Some blacks, offended by what they see as a demoralizing portrait of Jim and frequent use of racial slurs, have protested “Huckleberry Finn” as a racist novel.

Twain defenders, meanwhile, maintain that the author used his characters’ casual cruelty and insults to draw attention to the injustices of the Old South.

Rawles, a Seattle-based writer and amateur historian, spent months researching the personal histories of slaves, traveling to Twain’s home town of Hannibal, Mo., and reading oral histories, before writing “My Jim.” The book was published in January and is already in its third printing, with about 20,000 copies in print.

Alan Miller, a veteran literature teacher at Berkeley (Calif.) High School, heard about “My Jim” and was delighted to assign it to his 11th-grade students – so he could “teach ‘Huck’ right,” he said.

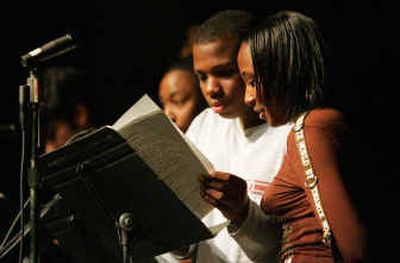

Earlier this month, with Rawles’ help, Miller’s students staged a dramatic reading of excerpts of “Huckleberry Finn” and “My Jim,” woven together for an audience of 150 classmates.

The audience, rapt during the reading, cheered when it ended. Students later asked Rawles about her research and her thoughts on “Huckleberry Finn.”

“People like to read it as this great adventure story, but it’s a whole lot more than that,” Rawles said. “And Jim is a whole lot more than that.”

In “My Jim,” Rawles envisions many elements of the story through Sadie’s eyes.

Jim’s owner, Miss Watson, tries to teach Huck manners in Twain’s book. She’s more peripheral and less proper in “My Jim,” where Rawles depicts her as a woman who vies for Jim’s attention and pulls him from his family.

In “Huckleberry Finn,” Jim is portrayed as superstitious; in “My Jim,” he has powerful spiritual vision that allows him to help his family and gain the respect of whites.

In recent years, many scholars, including Rawles, have argued that “Huckleberry Finn” is an anti-slavery book that was as progressive as could be expected, given the blatant racial hostility rampant in the United States when Twain wrote it.

But since the 1950s, at the beginning of the civil rights movement, many parents and community leaders – particularly blacks – have tried to evict the book from library shelves and seek court orders barring its use in classrooms. Courts have consistently resisted, citing free speech issues.

As recently as last year in Renton, Wash., a Seattle suburb, a black family tried unsuccessfully to have the book removed from school reading lists.

Such opposition has made it one of the most challenged books in American literature, said Carol Brey-Casiano, president of the American Library Association, who was happy to learn about “My Jim.”

“It provides an alternate point of view, that Jim was a real person, he had hopes and dreams like everyone else,” she said. “This is an opportunity to look historically at some of the attitudes in our nation.”

Brian Holbert, a senior at Berkeley High, disliked “Huckleberry Finn” when he read it last year because it didn’t address slavery more directly.

“I don’t think there’s really a good example of literature we can use that really teaches about slavery,” he said.

Now, though, “My Jim” has tweaked his interest and he plans to read the book.

On the other hand, David Singer-Vine, a student in Miller’s class, criticized “My Jim” for not allowing “Huckleberry Finn” to stand on its own.

“I don’t know that (Twain) would want to distort his work this way,” Singer-Vine said. “She (Rawles) didn’t know anything about what he wanted.”

Rawles disagrees.

“I think he’d be thrilled that ‘Huck Finn’ was still being read,” she says.