Floodwaters may finally do town in

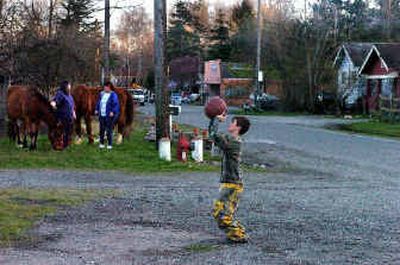

MARIETTA, Wash. – Once a thriving fishing community, this small town has changed along with the river that provided for it.

On Marine Drive just a few miles outside of Bellingham, Marietta is a stark contrast to much of fast-growing Whatcom County. A spray-painted real estate sign in front of a rotting home warns “No Yuppies!” The town lost its 98268 ZIP code, and its combination grocery store, gas station and post office long-since shuttered.

And now the town itself may be lost forever.

With the Nooksack River and storm water often rushing through Marietta’s streets, the county has plans to buy out the flood-prone town. By razing more than 20 homes and abandoned buildings, officials would return the area to a flood plain.

But the residents who have carved out a home here see Marietta differently, as a chance to have their own tight-knit community. And with some of the lowest property values in the county, the town represents their only chance to own a home.

“I’m not selling my house,” said Paul Ridley, a Marietta resident and a Vietnam veteran. “They don’t have the money to buy me out.”

The county’s plan, outlined at a Feb. 15 County Council committee meeting, would involve a long-term buyout plan for the area. The town’s dike, which is filled with unknown material, allows water to ooze through the soil. Coupled with storm water coming over roadways during hard rains, Marietta quickly can flood.

The cost of improving Marietta’s levee is estimated at $984,000. County officials predict buying out and demolishing the 122-year-old town would cost $852,000 – a higher benefit for the county’s cost, which could open the project to federal grant money.

Paula Cooper, the county’s river and flood manager, summed up the options for the council during the meeting: “Rebuilding the levee is going to be too expensive.”

News of a potential buyout shocked 24-year-old April White. She and her husband, Ken, have spent the last four years remodeling their home.

“Ten grand for a two-bedroom house,” she said. “Where else am I going to find it for that much other than on two wheels or in a trailer park?”

White, whose 2-year-old son Kenny drowned in the Nooksack River a year ago, said her neighbors rallied around the family during their tragedy.

“I’d rather not live anywhere else than here,” she said. “The support I have in the community is more than I’d get anywhere else.”

Ridley agrees.

“We’re not giving up our homes,” he said. “Where else am I going to live with all of my family?”

Ridley’s brick and mortar home abuts the leaking dike, its sandbag-lined top in his back yard. Going through reams of papers outlining past cleanup efforts by residents of Marietta, he rattled off a list from memory: 500,000 pounds of trash and garbage removed, 237 abandoned vehicles taken away and 14,000 pounds of appliances disposed of.

Though receiving help from the county during cleanups and for mowing along drainage areas, Ridley said the county’s public works department has yet to help improve the leaking dike, despite repeated telephone calls and faxes.

“We can’t play by their rules, they don’t give us the means,” he said. “They’ve turned deaf ears to our requests to maintain the dike.”

A buyout also could shortchange residents. Property owners would receive a “fair market value” for their homes as determined by an independent appraiser. However, with property values lower in Marietta than other parts of the county, it would be difficult for residents to buy land elsewhere.

Though the county’s public works department presented the plan during a public meeting, none of Marietta’s residents were invited to attend it. Most found out about the plan only after being contacted by a reporter last week.

After receiving a barrage of telephone calls over the proposed buyout from Marietta residents, Cooper said no firm decisions have been made on how to approach the Marietta situation.

“We’re still trying to figure out what to do with that area over all,” she said. “It’s a difficult problem area.”

County Councilwoman Barbara Brenner, who represents Marietta, had the impression the public works department already had contacted residents about the proposed buyout.

“When we have public meetings, we believe people who have requested to be involved should be involved,” she said. “To not invite them personally … it may be legal, but it’s not very ethical.”

Brenner met with Marietta residents to discuss the proposed buyout. She also plans to accompany public works officials to the town.

“I have a soft spot for Marietta,” Brenner said. “It’s such an old type of a community and I appreciate that. The way the county is changing and modernizing so much, it’s nice to see a place with some history.”

And for Paul Ridley’s wife, Karen, its history makes for tight bonds between her neighbors.

“If people drive through it, it looks like a neglected old place,” she said. “But I could go run out on the street and holler and everyone would come to see what’s wrong.”