Go back in the water

Just when you thought it was safe to go back to the video store …

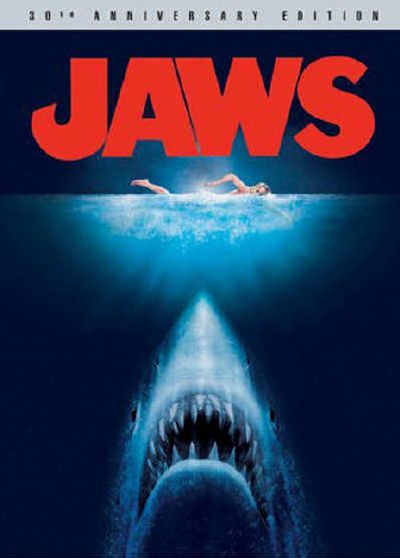

It’s been 30 years since “Jaws” first swam into movie theaters, gobbling up movie admissions, scaring away summer swimmers and confirming Steven Spielberg’s status as the industry’s most successful young director.

And now it’s back, in a deluxe DVD set released this week complete with outtakes, deleted scenes, a feature-length documentary and a “commemorative photo journal.”

But in some ways, the big fish never went away at all.

It lived on for years through the usual sequels: “Jaws 2,” “Jaws 3-D,” “Jaws: The Revenge.”

There were jokes on “Saturday Night Live,” a best-selling behind-the-scenes book and a decade of spinoffs, or ripoffs: “Piranha,” “Alligator,” “Orca.”

“I was even asked once,” confesses original screenwriter Carl Gottlieb, “to write a film about a killer bear, called ‘Paws.’ “

But “Jaws” lives on in other ways, too. The idea that you could get people to see a movie and then keep them coming back with separate sets of friends, as if it were an amusement-park ride – that began with “Jaws.”

The idea that you could open a movie big and make a lot of money fast – that began with “Jaws,” too, a movie that essentially invented the summer blockbuster.

The odd thing is, it almost was never made at all.

“If we had read the book twice, we never would have done it,” says producer David Brown.

On a second read, he says, anyone with any experience in the business – and he had decades – would have seen the ridiculous, if not insurmountable problems: How much would the extensive location shooting cost? How do you film a man-eating shark attacking a boat?

But Brown and partner Richard Zanuck read the galleys to Peter Benchley’s book only once, and all they saw was a gripping adventure story.

First, though, they had to get the right director.

“We didn’t want a safe director, an accomplished mechanic who would simply get the shots,” says Brown, 89. “We wanted someone who would bring another element to it, someone who wasn’t at that point the obvious choice for a big action film.”

They went through a couple of possibilities first, people Brown politely refuses to name even today. (One lost the assignment when, during an exploratory lunch, he kept talking excitedly about “the whale.”)

Then they thought of Steven Spielberg, who’d done a small, gritty car-chase movie called “The Sugarland Express” and a dazzling TV movie about a psycho truck driver called “Duel.”

“Steven wasn’t sure he wanted to do it,” Brown says. “He felt ‘Jaws’ was going to be a movie. He was more interested in making a ‘film.’ “

Brown pointed out that after Spielberg had at least one hit movie to his name, he’d be free to make all the small, personal films he wanted. He signed on.

“I think because I was younger, I was more courageous (then),” Spielberg explains in the new DVD’s accompanying documentary. “Or I was more stupid? I don’t know which.”

The casting was next. Benchley – influenced, perhaps, by Zanuck and Brown’s last big hit, “The Sting” – wanted Robert Redford and Paul Newman, with Steve McQueen for good measure.

Other names – Charlton Heston as Chief Brody? Victoria Principal as Mrs. Brody? Jan-Michael Vincent as Hooper, the scientist? – floated in and out.

Finally, Spielberg signed Roy Scheider, an actor still known mostly for a supporting part in “The French Connection,” to play Brody. Richard Dreyfuss was approached to play Hooper; he turned it down – and then had such sudden career worries, after an anxious screening of his own “The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz,” that he meekly asked for the part back.

Quint, the movie’s colorful Ahab, was harder to find. Finally Zanuck and Brown suggested Robert Shaw, a veteran character actor they’d worked with in “The Sting.”

For tax purposes, Shaw was living in Ireland and limiting his time in America. “Every so often during the shoot,” Brown says, “he had to fly up (and stay in) Canada for a few days.”

Benchley did the first work on the script; other writers, including Spielberg, did their own versions.

Finally Gottlieb, an improv comedian and story editor on TV’s “The Odd Couple,” was brought on board to rework Benchley’s draft. He went on location with the crew to Martha’s Vineyard, playing the small part of a newspaper reporter and rewriting scenes as they shot.

“It’s not an ideal way to make a movie,” says Gottlieb, whose best-selling book about the movie, “The ‘Jaws’ Log,” was recently updated and republished.

“But if everybody’s participating, without ego, there’s an urgency to it. … The actors end up discovering their characters almost as the audience is.”

With the actors in place, the movie still needed a shark.

The filmmakers’ first idea – couldn’t a shark be borrowed from an aquarium and trained? – was quickly dropped. Australian footage of a great white attacking a cage holding a stunt actor (actually a midget, to make the shark look bigger) yielded some shots but not enough.

Eventually it was decided to build an animatronic shark that could open its mouth, swivel its head and travel short distances on an underwater track.

It then spent much of the shoot refusing to work.

“Yet what first seemed like a liability, the inability to get extensive shark footage, turned out to be a boon,” Brown says. “Because when you don’t see the shark, you have to imagine it. The imagination of the audience is always far more powerful than anything you can put on screen.”

There were a host of other problems. The mechanical shark sank, as did one of the boats; varying weather made it hard to match shots; a camera, fully loaded with exposed film, fell in the water and had to be rushed to the lab for salvaging.

Slowly – sometimes at the rate of only two shots a day – Spielberg pushed on.

“Dick and I knew one truth about the business, which is don’t ever stop shooting or they won’t let you start again,” says Brown. “So even though we saw our work in jeopardy on an almost daily basis, even as we saw artificial sharks plunging to the bottom of Nantucket Sound and possibly taking our careers with them, we kept going.”

Somehow, it all came together, with different hands contributing different things.

Gottlieb took a look at Shaw’s competitiveness and dislike of Dreyfuss and wrote that into the Quint-Hooper relationship. Shaw rewrote his own monologue about the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis – a scene every screenwriter had tackled, and failed.

The finale was uncertain until the end, with Benchley calling Spielberg’s compressed-air-tank idea ludicrous (and Spielberg toying with having Scheider kill the shark – only to see, in the distance, several other fins headed towards him).

Even after shooting stopped – after a numbing five months – the work continued. John Williams composed a score that swung from heroic “Sea Hawk” style fanfares to ominous, rhythmic rumbles. When the discovery of the old fisherman’s sunken corpse didn’t get the reaction he wanted at test screenings, Spielberg shot additional close-ups in film editor Verna Fields’ pool.

Gottlieb recalls going to another test screening where, as the audience shouted and applauded over the credits, Lew Wasserman and other top Universal Pictures executives ran into the men’s room for quiet and hastily figured out a new release strategy.

And this is the point where the story of “Jaws” the movie becomes the story of “Jaws” the phenomenon.

The movie industry had had hits before. The last big one had been “The Godfather.” The one before that, “The Sound of Music.” The original, “Gone With the Wind.”

All were movies that opened in big cities with some publicity, moved slowly out into the suburbs, and, says Gottlieb, “finally reached Sioux City six months later.”

“Jaws,” however, opened wider and a lot bigger, with an onslaught of network TV ads – still a novelty in 1975.

It made money faster, too. It outgrossed “The Godfather,” and “The Sound of Music,” and “Gone With the Wind” – and weeks later, still was minting money. At a time when movie tickets cost about $3, it made a million dollars a day, over $100 million in its first run. Nothing like it had ever been done before.

” ‘Jaws’ changed release patterns forever,” says Gottlieb. “The wide-scale, multiple-screen releases, the phenomenon of people returning to watch a movie three or four times – ‘Jaws’ began all that. Those juggernaut tentpole pictures you see every summer now – ‘Jaws’ set that pattern.”’

Brown accepts the praise, but not the blame for what followed.

“It was a predecessor of those (blockbuster) films,” he admits, “but with a caveat: It was not an infantile one. It’s not a mindless movie.

” ‘Jaws,’ when I see it occasionally on television, I’m quite astonished at how undated it appears to be. It’s a film that stands up and stood the test of time. It’s not a period piece. … It’s just a good picture.”