Payne and suffering

PGA Tour rules official Jon Brendle was setting up the course for the Byron Nelson Championship last month when he reached a spot on the TPC at Las Colinas that caused him to think of Payne Stewart.

“I remember he chipped in one year on No. 6,” Brendle said. “I got out of my cart and tried to do it.”

Hal Sutton thinks about Stewart when he goes into locker rooms, where nameplates usually are in alphabetical order.

“Most of the time, our lockers were side by side,” Sutton said.

It was especially poignant at Disney, Stewart’s last PGA Tour event. Stewart’s locker now is covered with a glass door, showing his red plus-fours on a hanger, a white shirt with his silhouette stitched in navy blue on the chest and a white tam-o’-shanter cap on a hook, all dangling above white shoes and a worn glove.

Davis Love III was digging out old pictures while working on a project with his son recently when he came across a photo of Stewart puffing on a cigar, mischief in his eyes as he celebrated victory in the Ryder Cup, the last trophy he hoisted.

“Definitely a high point, getting to play with him and then learn from him,” Love said.

Stewart has been gone for more than 5 1/2 years, one of six people who died when a private jet presumably lost cabin pressure and incapacitated all aboard, then flew uncontrolled across the country until it ran out of fuel and plunged into a South Dakota pasture.

The PGA Tour named an award after him. Players say they will never forget him.

At this U.S. Open, his memory will be impossible to ignore.

Pinehurst No. 2 is renowned as one the best courses in America, defined by the domed greens created by Donald Ross. But there is an unbreakable bond between Payne and Pinehurst.

“That was his best triumph,” Stewart Cink said. “I remember a little about other majors he won, but Pinehurst was quite dramatic. And then, the crash a few months later. To me, he is forever going to be held with Pinehurst, together.”

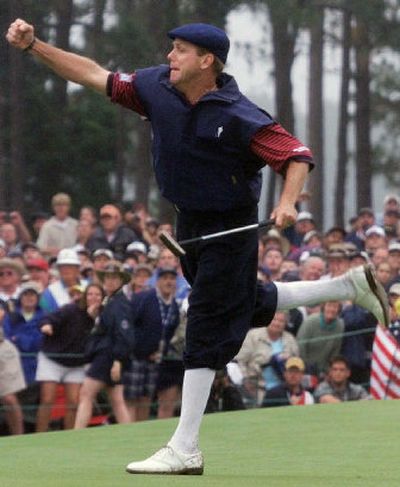

The image of Stewart’s victory is captured in a bronze statue that now overlooks the 18th green, where he holed a 15-foot par putt, the longest to win a U.S. Open. His right fist punches the air in victory, the putter dangling from his left hand and his right leg stretched behind him – a perfect pose.

It was a proud moment, Stewart’s finest.

“It’s going to be an emotional week for everybody,” Phil Mickelson said.

Memories run particularly deep for Mickelson, who finished one shot behind Stewart. Mickelson’s wife was expecting their first child, and he carried a pager in his bag with a pledge to leave Pinehurst if she went into labor.

Moments after Stewart made the clinching putt and leapt into his caddie’s arms, he placed both hands on Mickelson’s cheeks and told him, “Good luck with the baby. There’s nothing like being a father.”

Mickelson’s daughter, Amanda, was born the next day.

“Here he just won the greatest championship of the game, and he’s thinking about Amy and myself,” Mickelson said. “He’s very prophetic, too. Being a father is the most fulfilling thing that I’ve ever experienced in life.”

The 1999 U.S. Open simply was one of the best ever played.

Not only was it a daylong duel between Stewart and Mickelson, but Tiger Woods and Vijay Singh were right behind. It came down to the final three holes, starting with a 25-foot, double-breaking, downhill par putt that Stewart made on No. 16, giving him a share of the lead when Mickelson missed his par putt from 8 feet.

Stewart surged ahead with a 3-foot birdie on the 17th, while Mickelson missed from just outside him.

And then came the final hole.

Stewart hit into the right rough off the tee and laid up, and when Mickelson hit his second shot into 25 feet, the tournament could have gone either way.

Mickelson’s birdie putt came up inches short, and Stewart won the Open with a par putt that was worth its weight in bronze.

“You could just see in his emotion how much he wanted to win that tournament,” Ernie Els said.

Wearing a navy waterproof jacket with the sleeves torn out – Stewart always made a fashion statement – he cradled the U.S. Open trophy as if it were his first-born child.

Four months later, he was gone.

His plane crashed on Oct. 25, 1999, as he was going to inspect a golf course in Dallas before heading to Houston for the season-ending Tour Championship.

Stewart was the first U.S. Open champion not able to defend his title since 1949, when Ben Hogan was recovering from a near-fatal car crash. The next year at Pebble Beach, players lined the 18th fairway on the day before the U.S. Open and hit tee shots into the ocean, their own 21-gun salute to Stewart.

Even now, it is hard to believe he’s gone.

“I didn’t know he was so famous,” said Paul Azinger, his best friend on tour. “I didn’t know he had a magazine. I didn’t realize if he were to die, his funeral would be aired in 120 countries around the world. It was mind-boggling. Everybody knew him.”

Stewart once put his mansion in Orlando, Fla., up for sale, and one prospective buyer was Michael Jackson. The King of Pop had no idea who the owner was until his manager told him Stewart was the golfer in colorful knickers.

“Oh,” Jackson said, “that guy.”

His death left a void in golf and devastated his family. Tracey Stewart, his widow, rarely is seen outside her home at Isleworth Country Club near Orlando. His daughter, Chelsea, is 19 and just finished her freshman year at Clemson. Aaron is 16 and scheduled to play in a junior tournament the week of the U.S. Open.

Tracey Stewart wasn’t planning to go to the U.S. Open, anyway.

“I miss him every day,” she told Golf Digest magazine. “Some of my friends tell me I have to move on, and I understand why they say that. But I still feel as if it happened last week, even though I know it’s been much longer than that. I try not to be sad when I think about him. And there are so many wonderful memories.

“But when I think back to where Payne was in his life when he died, how happy he was with his family, with his golf, with himself, it makes me so sad.”

Stewart will be a central figure at this U.S. Open, and always will be linked with Pinehurst.