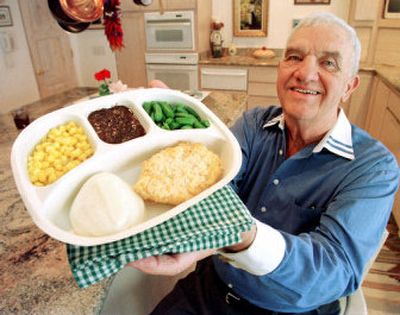

TV dinner inventor, 83, dies of cancer

PHOENIX – Gerry Thomas, who changed the way Americans eat – for better or worse – with his invention of the TV Dinner during the baby boom years, has died at 83.

Thomas, who died at a Phoenix hospice center on Monday after a bout with cancer, was a salesman for Omaha, Neb.-based C.A. Swanson and Sons in 1954 when he got the idea of packaging frozen meals in a disposable aluminum-foil tray, divided into compartments to keep the foods from mixing. He also gave the product its singular name.

The first Swanson TV Dinner – turkey with cornbread dressing and gravy, sweet potatoes and buttered peas – sold for about $1 and could be cooked in 25 minutes at 425 degrees. Ten million sold in the first year of national distribution.

It was fast and convenient, and fit nicely on a TV tray in the living room, so that you didn’t have to drag yourself away from your favorite television show.

Robert Thompson, director of the Center for the Study of Popular Television at Syracuse University, said the TV Dinner “started a change in American eating habits bigger than any change in culinary history since the discovery of fire and cooked foods.”

The TV Dinner fit in with societal changes at the time, when more women were entering the work force and did not have the time to spend all day preparing dinner, Thompson said. It also helped introduce the notion of “modular” eating: If there were only two people at home, you put only two dinners in the oven.

“Some people claim that the TV Dinner was the first step toward breaking up the American family because it made it possible for everybody to eat in a modular way,” Thompson said. “That was going to happen anyway. The redefinition of the American family was going on anyway.”

In a 1999 Associated Press interview, Thomas recalled that the inspiration for the TV Dinner came when he was visiting a distributor, spotted a metal tray and was told it was developed for an experiment in the preparation of hot meals on airliners.

“It was just a single compartment tray with foil,” he recalled. “I asked if I could borrow it and stuck it in the pocket of my overcoat.”

He said he came up with a three-compartment tray because “I spent five years in the service so I knew what a mess kit was. You could never tell what you were eating because it was all mixed together.”

Since interest in television was booming, he added: “I figured if you could borrow from that, maybe you could get some attention. I think the name made all the difference in the world.”

“We had the TV screen and the knobs pictured on the package. That was the real start of marketing,” Thomas said.

The TV Dinner drew “hate mail from men who wanted their wives to cook from scratch like their mothers did,” Thomas said, but it got him a bump in pay to $300 a month and a $1,000 bonus.

After the Campbell Soup Co. acquired Swanson in 1955, Thomas became a sales manager, then marketing manager and director of marketing and sales. He left the company after a heart attack in 1970.

He later directed an art gallery and did consulting work.

“It’s a pleasure being identified as the person who did this because it changed the way people live,” Thomas said. “It’s part of the fabric of our society.”

But Thomas went decades without recognition for his innovation, said his wife, Susan Thomas. Even his seven children were not aware of his place in modern American life, but after his contribution was recognized in the mid-1990s by marketers at Swanson, “it just had a life of its own,” she said.

Thomas relished the credit he got for his invention and even kept the original prototype tray and packaging for the TV Dinner, Susan Thomas said.

But that didn’t mean he ate them.

“He was gourmet cook,” Mrs. Thomas said. “He never ate the TV Dinners.”