Helping to make the world a better place

He handed me a quotation, typed in letters half an inch high: “A hundred years from now, it won’t matter what my bank account was, the sort of house I lived in, the kind of car I drove. But the world may be different because I was important in the life of a child.”

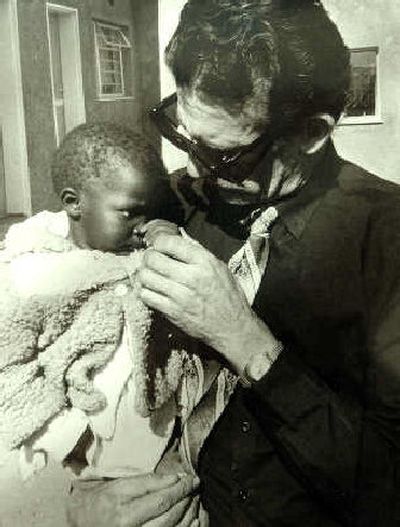

He’s lived in a chicken coop and a sprawling country home on a quarter section of prime farmland. He’s owned businesses worth more than $1 million, and he’s also laid awake at night wondering how he’d pay his electric bill. But rich or poor, his prime concern has been the welfare of the children in his care. A hundred years from now the world will be a better place because Hank Stelzer lived.

Stelzer has spent the last 25 years living and working in Lesotho, (pronounced “Lesutu”) a tiny, mountainous country completely surrounded by South Africa. Legally blind since 1975, he began his foreign mission as a Peace Corps volunteer, and from there continued a one-man crusade, establishing a boarding school and training center for blind children.

Stelzer’s work with the Peace Corps involved translating Lesotho Braille into English Braille and teaching at the school for the blind in Maseru, the capital city. He soon became disenchanted with the system, because “they were learning not just English, but ENAR, English for No Apparent Reason. Some of the students had been there for 15 years, and there wasn’t even one blind person employed in the entire country.”

Upon receiving Stelzer’s resignation letter, the Peace Corps made plans to send him back to the United States. Hank said he wanted to stay in Lesotho and work. The administration insisted that protocol demanded they send him back. He suggested they give him the cash instead of buying a return plane ticket. His arguments went nowhere and he landed back in Minnesota, where he immediately sold 120 acres of farmland, and headed back to Lesotho to build his dream school for the blind.

What started as a 12-foot-by-14-foot Masonite building, housing 10 young blind women grew into a two-story cement-block boarding school that served 32 students and included classes in Braille, typing, carpentry, gardening, animal husbandry and switchboard operation.

The single feat of which Stelzer is most proud is that he collected and distributed 10,000 pairs of glasses, aided by Lions International. Stelzer recalls, “One man in his early 70s who couldn’t see to read, came to our center for a pair of glasses. He had one leg and walked on crutches. Our center was on a plateau six miles from the village. A few months later, this man walked those six miles on his crutches, up that steep hill, carrying a small plastic bag. He’d come to thank me for the glasses with a gift of three sweet potatoes.”

Stelzer has since turned the school over to the people of Lesotho. Thirteen students from his school have landed real jobs, the first blind people ever to work in Lesotho. They are currently raising chickens, knitting sweaters, working as telephone operators and bank receptionists. One organized a band, and another is working at the University of Lesotho.

Stelzer’s life story could fill a book, and would, of course, be published in Braille, and would include stories of building, selling and losing million-dollar businesses in machine repair, wool sales and transportation; educating and building housing for countless employees; being jailed, almost deported, robbed 13 times and shot in the stomach at close range with a .38-caliber weapon; a suicide attempt and the dissolution of a 20-year marriage; witnessing a dozen coups d’etats and three civil wars. And despite everything, fighting for permanent resident status in his adopted country.

At 75, he is now involved in the management and operation of an orphanage. He’ll be heading back to Lesotho in November to install a new stove in the orphanage kitchen.

“There was an old, four-burner stove used to make meals for the orphans. A couple women from the village wanted to learn how to make pancakes, and pretty soon 20 women were making 20-30 pancakes each, at four o’clock every morning on that old stove. They’d sell them in the village for about 30 cents apiece, and make more money in four days than they could make in a month selling cabbage and spinach in the market. But that old stove finally gave up the ghost. It’s down to one burner. The ladies at Trinity Lutheran Church here in Coeur d’Alene have pledged enough money to buy a new stove when I get back.”

Stelzer’s trips to Lesotho are now limited by his ability to fill his medical prescriptions. He has an appeal in to Sen. Larry Craig which would allow his medications to be sent through the American Embassy in a diplomatic pouch so that he can lengthen his stays.

Asked what motivates him to continue his humanitarian work, Stelzer says, “I grew up in the Depression. My family was extremely poor, and I’ve always hated greed. I just do what I can to help alleviate poverty in the world.”