Boys do cry

Think about the grim, stoic, faces of the frightened soldiers and weary firefighters you see in the newspaper and on the 11 o’clock news. Think about the bitter, angry women who complain that their silent husbands don’t respond, don’t show love and emotion, and don’t reach out for them. Think about the ordinary men who go through the worst life has to offer – the death of a loved one, a divorce and fight-to-the-death custody battle, the loss of a job or career – with clenched teeth and clenched fists, but without making a sound. Think about when you were a kid and you saw a little boy fall on the playground, taking the skin off his knees, and get right back up, biting his lip to hold back the tears. Think about the first time you heard these words: Big boys don’t cry.

Think again.

Twice a year, in the early spring and again in the fall, men come together in a room in the lodge at Fort Wright for a series of eight classes called “Men Have Issues, Too.”

At the first meeting they are quiet. They don’t look at one another and they don’t have a lot to say.

Some have found the class because they are looking for a way to deal with grief or with a divorce, or to interact with other single fathers.

Others are there because a court ordered them to learn anger-management skills.

A few of the men are there because they were asked, or begged, to sign up by a loved one – a wife or partner.

The man who leads the class opens by telling them a little about himself. And the first thing he tells them is that he can relate.

At 66, Don Barlow is soft-spoken. When he talks about the tools men need to deal with stress, he isn’t handing out formulas from a textbook.

He knows firsthand the issues with which many of the men in the room are struggling.

His first marriage ended in divorce. His second wife died of cancer, leaving him with a 6-year-old daughter.

“I was devastated,” Barlow admitted. “I looked at my little girl, and I thought, I can’t do this – the wrong one died.” He learned to be a single parent, and he survived the loss of a stepdaughter and an adopted son to cancer.

In addition to holding a doctorate in education, Barlow, who is also a licensed mental health professional and a trained counselor, brings his own experiences to the group. He teaches survival because he is a survivor.

Each man brings his own story.

For some, just showing up is the first strike in an effort to chip away the walls they have spent a lifetime building.

Others are there because they want what women instinctively give to one another: the comfort, companionship and emotional safety of a close-knit group.

But what most bring away are the skills needed to navigate through the ups and downs of an ordinary life.

And if they need to, they cry.

I could see the things that were built into me

Dave Stecher is a quiet man. He pauses between words, thinking carefully about what he wants to say. He wants to get it right.

The 50-year-old, a customer-service representative for a mail-order pharmacy, lives in rural Mica, southeast of Spokane. He has been married for 29 years and has a 26-year-old son and a 19-year-old daughter.

Stecher came to Barlow’s class after his wife handed him a brochure and told him to think about going.

“She was right,” he said. “I was overwhelmed.”

In his late 40s, Stecher was reeling after the deaths of his mother-in-law, mother and grandmother in less than a year.

“I was very close to each of those women, and to be honest, I didn’t know how to deal with it after they died,” he said.

The back-to-back losses of three important women in his life forced him to confront the idea of his own mortality. He began to feel the strain at work and within his relationships with others.

“I learned that you can’t ignore that kind of thing, hoping it will go away, because it doesn’t,” he said. So he signed up.

In the beginning, Stecher was uncomfortable in the room full of strangers, but he quickly discovered that in spite of the differences in their ages, occupations and social situations, there was a common bond.

“You see pretty fast that a lot of other people feel like you do,” he said. “Things opened up and got easier.”

Stecher appreciated being able to talk freely about his concerns.

“We’re trained that you don’t cry, you don’t do certain things,” he said. “But things like grief, death and divorce boil up inside you.”

He began to see a change in the way he related to his wife and children.

“Like a lot of men, I felt like I had to be out there working; I had to be the breadwinner,” he said “It opened my eyes to the way I was raised and the things that were built into me.”

After Stecher’s class ended, he lost touch with the men in his group. He wishes they had agreed to meet informally, as a kind of support group.

“When you sit in a room with a bunch of gentlemen, and it gets emotional – and I cried too – it changes things,” he said. “I came away a stronger person.”

As life goes on, you get hard

To hear Floyd Kendrick tell it, his life has been a long lesson in learning the hard way. He is 64 years old, with a mane of silvery Kenny Rogers hair and dark eyes peeking out from under his brows.

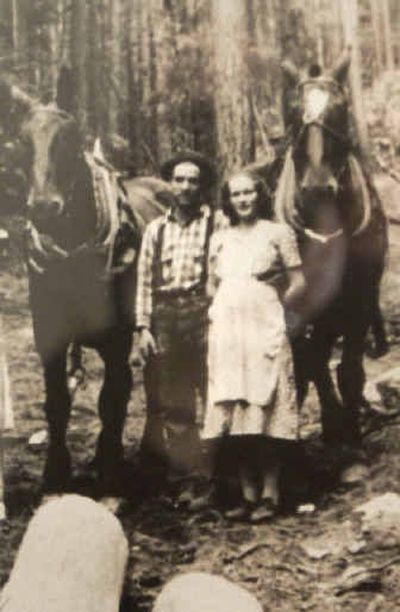

Kendrick and his brother, Dale, grew up in Spokane. Their father was a logger, and the pair spent each summer living out of a school bus that had been converted into a camper.

Kendrick learned early to introduce himself to each new logging camp with his fists.

“I don’t know how it is with girls, but for us boys you had to fight to survive,” he said. “That’s how you found your place.”

Against his father’s wishes, Kendrick left school after 10th grade. He married when he was 21.

A baby daughter was born but lived only a month.

“That was real tough, but I didn’t talk much about it,” he said softly. “I figured it must have been worse for my wife because, you know, she carried her.”

Kendrick grew up in a time when men kept their suffering to themselves.

“When I was younger, I thought I wasn’t supposed to show emotions,” he said. “But that way, as life goes on, you get hard.”

The death of his father in 1966 – he was struck by a drunken driver while changing a flat tire late at night on Market Street in North Spokane – hit Kendrick hard.

“Losing my dad kind of took the sap out of me,” he said.

Then in 1975, his marriage broke up.

“I went from my home with my parents and my brother, into a family with my wife,” he said. “Then one morning, I woke up and I was alone.”

His young daughter and son remained with his ex-wife. He felt isolated and unnecessary.

The divorce damaged his relationship with his children, especially with his daughter.

“My daughter has me painted as the bad guy now, but when she was a little thing, she was my buddy. She’d see me and just come a running,” he said.

“I still miss that.”

Kendrick admits he didn’t handle the isolation well. He drank and got into a scrape with the law. He made slow progress.

“It took me seven years, financially as well as emotionally, to get over it,” he said.

He went back to school, got his GED and took courses at the community college before remarrying 12 years ago.

When he saw a story about the “Men’s Issues” class in the newspaper, he showed it to his younger brother, who had married and divorced twice. The pair signed up.

“My brother and I talked about the things we had been through, with marriage and losing our dad and everything, and we decided to go,” Kendrick said.

They were surprised to see men of all ages when they went to the first class. Each had a different reason for being there, but the group soon bonded over their similarities.

“We talked about going through life, divorce, jobs. … It was pretty important,” Kendrick said.

Having completed the series of classes, Kendrick is a believer in what he calls the power of the group. He thinks it might have made a difference if he’d had that kind of support when he was a young man.

“You know, losing my dad just devastated me, the same with my divorce with my first marriage; it always felt like a power struggle,” he said. “It helped to know other people had been through the same thing.”

Society expects us to handle it, but we don’t always have the tools

Dale Kendrick, 60, is self-employed. He has silver hair, like his older brother, but it is cropped in a youthful cut, and his eyes are blue. They look away from you when he talks about losing his father.

“I was 22 and it hit me hard; I lost my direction, my motivation, for a while there,” he said.

“You know, when things like that happen, society expects us to handle it, but we don’t always have the tools.”

As with his brother, Dale Kendrick’s first marriage ended in divorce. So did his second.

He married for the first time at age 20 and had two sons. The marriage broke up after 20 years.

He got married again, to a woman with two children of her own. That marriage lasted only eight years.

“I think we kept things too separate and never made it into a partnership,” he said.

After that, he lived with a woman for five years.

“She was much younger, with two little children, and I thought she needed me,” he said. “But – I don’t know – in the end it just didn’t work out.”

Alone and back in Spokane, Dale Kendrick paid attention when his brother showed him the information about Barlow’s classes.

“I was curious because it sounded supportive,” he said. “And I was alone, going nowhere.”

In the group, the brothers found others who dealt with the same kind of isolation.

“I had this feeling that no one other than my brother cared,” Kendrick said. “He was very supportive of me,”

It isn’t lost on Dale Kendrick that taking the class earlier might have helped him comfort that brother.

“I admit I wasn’t there so much for Floyd when he went through his divorce. I didn’t understand how he felt,” Kendrick said, “until it happened to me.”

Now, like the other men in Barlow’s classes, Kendrick believes he has the necessary tools to deal with the stresses and situations he encounters. And he wishes the same principles were taught to young men and boys through courses in high school and after-school programs.

The benefit, Kendrick believes, would be a generation of men who would be better equipped to live happy and productive lives.

“There is a very real need for that kind of support,” he said. “I wish more men knew about it.”