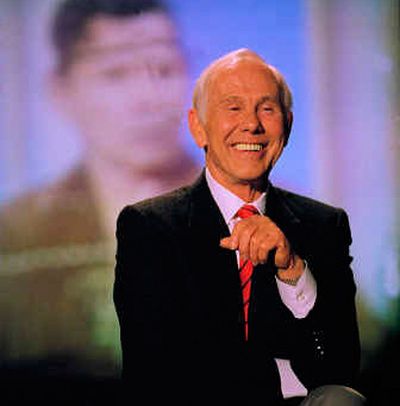

Good night, Johnny

“Heeeeere’s Johnny!”

That phrase – delivered in the booming baritone of Ed McMahon, backed by the theme song by Paul Anka – is as firmly ingrained as any in the history of television.

Johnny Carson didn’t invent late-night television, but he might as well have. For it was his “Tonight Show” that perfected the art of wee-hours talk, comedy and music, setting a gold standard punctuated by his genius for effortlessly wringing a laugh out of a well-chosen grimace or tie-straightening gesture.

Carson, 79, died Sunday morning. The cause of death was emphysema, according to NBC.

“He was surrounded by his family, whose loss will be immeasurable. There will be no memorial service,” his nephew, Jeff Sotzing, told the Associated Press.

In 4,350 shows over nearly 30 years, Carson’s “Tonight” reigned supreme. He made stand-up comics’ careers with a mere gesture, a “nice stuff” compliment that spoke volumes or an invitation to come sit and chat. Jerry Seinfeld, Roseanne Barr, David Letterman and his successor, Jay Leno, among many others, vaulted to stardom by warming Carson’s couch.

He wrestled with exotic animals brought by the likes of Jim Fowler and Joan Embrey. He embodied iconic characters such as the turtle-necked and turbaned soothsayer Carnac the Magnificent, tart-tongued Aunt Blabby, “teatime” movie host Art Fern and hayseed patriot Floyd D. Turbo that won audience hoots each time they appeared.

He provided a huge showcase to plug books, movies and TV shows. And he set a style standard with his own sporty clothing line, sold in hundreds of department stores.

And aside from cementing his own stature, he made household names out of McMahon and his bandleader Doc Severinsen, who replaced Skitch Henderson in 1967.

Through all of his antics, Carson was a comforting presence for millions of insomniacs and hundreds of comics, actors and singers who performed before his curtain. A consummate straight man, his Midwestern reserve, dry wit and easy grin put fans at ease and proved a marked contrast to the edgier late-night humor that would follow.

Even after his May 1992 retirement – when he disappeared from the public eye – he couldn’t completely let go. Peter Lassally, who worked with Carson for nearly 20 years, told television writers at a conference last week that Carson missed the monologues most. “When he reads the paper in the morning, he can think of five jokes right off the bat that he wishes he had an outlet for,” Lassally says. “But he does once in a while send the jokes to Letterman, and Letterman has used Johnny’s jokes in the monologue, and Johnny gets a big kick out of that.”

Started in magic

Born John William Carson in Corning, Iowa, in 1925, Carson’s family moved to Norfolk, Neb., where he began performing at 14 as “The Great Carsoni,” a comic magician.

After a Navy stint and four years at the University of Nebraska, he became a local radio announcer, and dreamed of emulating his idols Jack Benny or Fred Allen as an audio comic. He moved into the nascent world of television at an Omaha station in 1949.

His first show: “The Squirrel’s Nest,” a daily afternoon show with jokey interviews. A few years later, he moved west to Hollywood. He starred in “Carson’s Cellar,” a low-budget local series that attracted the attention of Groucho Marx, Fred Allen and Red Skelton. He became a writer for Skelton’s show and served as a substitute for the host when he was injured.

After breaking into prime time with a short-lived quiz show, “Earn Your Vacation,” he flamed out in 1955 with CBS’ failed “The Johnny Carson Show,” a comedy-variety show that depended on the 29-year-old Carson, who had yet to develop a TV persona.

His first big break came in 1957 as host of ABC’s game show “Who Do You Trust?”, for which he hired McMahon as his announcer. The exposure led him to serve as a substitute for Jack Paar, who endorsed Carson as his permanent replacement. Forced to ride out his ABC contract, Carson became “Tonight’s” permanent host on Oct. 1, 1962, six months after Paar’s retirement.

Under Carson’s reign, “Tonight” moved from black-and-white to color, from New York to NBC’s studios in “beautiful downtown Burbank,” Calif., in 1972, and in 1980, from 90 minutes to one hour. Two years later, his production company launched “Late Night With David Letterman” in the NBC time slot that followed.

Quick quips

There were many signature “Tonight” moments, some unplanned: The famous 1965 episode in which singer Ed Ames, demonstrating how to throw a tomahawk by aiming at a wooden sheriff, struck it squarely in the crotch, prompting Carson to ad-lib: “I didn’t even know you were Jewish.”

For many viewers, the most memorable “Tonight “episode was his next-to-last broadcast on May 21, 1992. A visibly choked-up Carson was serenaded by Bette Midler, astride his desk, and both fell into a touching duet of “Here’s That Rainy Day.”

That episode left such an indelible mark – and many a tear – that Carson reportedly wanted to end the show there. But he returned the next night for a finale, showcasing highlights and thanking viewers, with these words:

“And so it has come to this. I am one of the lucky people in the world. I found something that I always wanted to do and I have enjoyed every single minute of it.”

“You people watching, I can only tell you that it’s been an honor and a privilege coming into your homes all these years to entertain you. And I hope when I find something I want to do and think you would like, I can come back and (you will be) as gracious in inviting me into your homes as you have been.”

“I bid you a very heartfelt good night.”

And that was that.

Seven weeks after he retired, at age 66, Carson signed a lucrative deal with NBC to develop and star in unspecified new shows for the network. The pact was heralded by then-programming chief Warren Littlefield as “a very, very important announcement for all of NBC.”

But it came to naught: Instead, Carson promptly vanished from sight. Always an intensely private man, he retreated to his Malibu estate, played tennis daily, traveled, bought a yacht and spurned all pitches to resume work.

Private life was private

Carson married four times and divorced three, making frequent references to his marital troubles in nightly monologues. (He’s survived by his fourth wife, Alexis.)

But he was intensely secretive about other aspects of his life. One of his three sons, Ricky, a nature photographer, tragically died in a 1991 car accident while working.

Carson had health problems – a heart attack and quadruple-bypass surgery in 1999, emphysema revealed a few years later – but kept the news even from close friends.

He even passed on “Tonight” ‘s 50th anniversary special, explaining in his stoic, Midwestern way that he felt such appearances needlessly self-congratulatory.

His biggest (though perhaps unwarranted) worry, expressed to the Post in 1993, was that his return would bomb in the ratings and sully his legacy.

“You say, ‘What am I doing this for? For my ego? For the money?’ I don’t need that anymore. I have an ego like anybody else, but it doesn’t need to be stoked by going before the public all the time.”