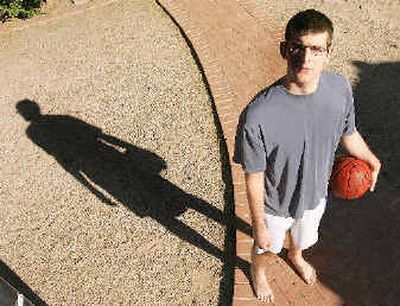

Former Arizona prep star rebuilds life after stroke

TUCSON, Ariz. — Joe Kay slammed in a two-handed dunk, leading his high school team to victory over the city’s perennial powerhouse. Fans swarmed the floor and Kay, his arms raised in celebration, was tackled by 10 to 20 jubilant classmates.

But moments after the lanky teen emerged from the pile, it was obvious something was seriously wrong with the star player and school valedictorian — who was preparing to attend Stanford on a volleyball scholarship.

Kay couldn’t talk or use the right side of his body because a major artery in his neck was torn. Blood wasn’t reaching the left side of his brain. On the day before his 18th birthday, Kay had suffered a stroke.

Nearly a year later, after months of full-time therapy in which he had to learn to walk and talk all over again, Kay planned to move this weekend into a dorm room at the University of Arizona and take three classes this semester. He still hopes to go later to Stanford.

“You have to deal with whatever comes at you,” Kay told the Associated Press in a recent interview at his Tucson home.

Within seconds, Kay’s life and future had been devastated.

His plans to go to Stanford were put on hold. The Tucson Magnet High School valedictorian missed the rest of his senior year. He couldn’t perform in a regional concert, where he had been slated to be the top saxophonist. Playing basketball and volleyball again became a goal.

Kay filled his days of therapy repeating antonyms and synonyms, stacking blocks, walking on a treadmill and doing other drills.

He still struggles with some cognitive skills and has very limited use of his right hand. But he has recovered better than many expected and has refused to succumb to self-pity, said his mother, Suzanne Rabe, a University of Arizona law professor.

The youngest son of Rabe and Fred Kay, the recently retired federal public defender for Arizona, Kay has always played sports. He was 6-foot-6 by his freshman year.

Kay’s talent and drive for sports mostly baffled his mother, who quizzed Joe and his sister about the Bill of Rights during dinner and jokes that she still doesn’t know how many points a free throw is worth.

But Kay remembers his dad taking him to shoot hoops at the neighborhood park in preschool. Joe wanted to be like his older brother, Alec, also a Tucson High star, who went on to play college basketball.

“One thing about Joe’s personality, he wasn’t easily defeated,” Rabe said. “He just always showed up.”

Kay has spent his life pushing coaches, teachers — and now therapists — who didn’t challenge him enough, said Alec Kay, who runs a physical therapy clinic with his wife in Anchorage, Alaska.

“He wants to be pushed. He’s not just there to skate along,” he said. “He’s very unusual in how much he’s progressed. He’s already surpassed sort of what I thought he would achieve in terms of recovery and return.”

Kay took his first steps with help from Alec’s wife, Laurie Macchello, just a month or so after the Feb. 6 stroke.

Macchello, a therapist who specializes in brain injury patients, found a handrail at the hospital one night. She strapped him into a harness and supported him.

“She screamed ‘WALK! WALK!’,” said Rabe. “And he did.”

“I remember that was probably the only happy day I’ve had since Joe’s injury,” his mother said. “That day was just pure happiness for me.”

Kay is reluctant to acknowledge his life has changed much in the last year.

“My friends, my family, the girls in my life are all exactly the same as before my stroke. Nothing has changed for me socially,” said Joe, who was known in high school as “Spicy Joe.” He once swallowed a golf ball-sized chunk of wasabi on a $10 dare.

But Kay concedes things have changed for him physically. He walks with a slight limp, and he struggles to do simple tasks like turning a door knob with his right hand. He hasn’t started driving again.

“The one thing that really bugs me is that I can’t play basketball,” said Kay, who has given up the dream of playing in college but hopes to play recreationally.

He still struggles occasionally with his speech, forgetting words or how to say them. Rabe said her son, who spent a week agonizing over whether to attend Stanford or Harvard before the accident, is not as articulate as before.

A math whiz who scored a perfect 800 on the math section of the SAT, he can add and subtract but now has more trouble with complicated problems.

Alec Kay said his younger brother is likely to find living on his own a challenge. The teen has refused to make concessions to his condition, like using slip-on shoes. That means things like zippers and shoelaces take lots of time.

But his friends and family say Kay has never wanted pity and hasn’t pitied himself.

“I’ve been waiting for some big emotional breakdown, and it’s not coming,” Alec Kay said.

“He’s still very much the same person,” said friend Gus Hoffman.