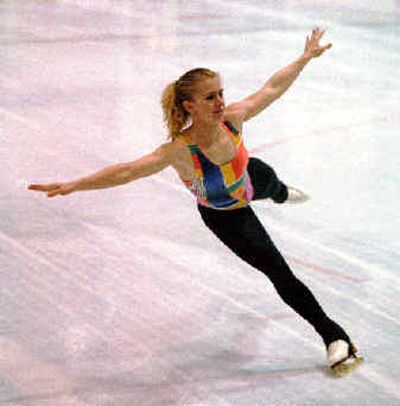

Harding was the pioneer of triple axel for women skaters

PORTLAND – Before the whack. Before the broken skate lace. Before the guilty plea and the community service and the forays into acting and boxing.

Before all of that there was a powerful, hardheaded skater and an amazing jump. For all of the tumult that Tonya Harding left in the wake of her figure skating career, she can hold up one untouchable accomplishment.

The triple axel.

It is the Everest of women’s figure skating, both terrifying and compelling. The only jump that starts on the forward foot, it explodes in 31/2 revolutions — yet demands a delicate touch on takeoff and iron strength on landing.

Harding became the first U.S. woman to land the jump in competition when she completed it 45 seconds into her free skate at the 1991 U.S. championships.

She remains the only one. No U.S. woman has completed the jump since.

“If you don’t have the guts to throw yourself up in the air and know that when you land, it will hurt if you don’t do it right, you won’t do it,” Harding said in a recent interview.

Four other skaters have landed the triple axel in sanctioned events. Japan’s great Midori Ito was the first, in 1988, and stunningly, she landed it twice in her 1992 Olympic free skate. More than a decade passed before Russia’s Ludmila Nelidina and Japan’s Yukari Nakano hit the jump, both in the 2002 Skate America in Spokane. Fourteen-year- old Mao Asada of Japan landed the jump at the Junior Grand Prix final this season, although critics say she fudged the landing and didn’t get the full rotation.

Others have claimed to have landed the jump – in practices – but have yet to produce on the public stage.

To crash on the triple axel is the norm. Figure skaters call that a “waxel.” As in, getting waxed by the jump.

After Ito first landed the triple axel, Japan’s figure skating association urged its young skaters to perfect the jump. Rena Inoue, a native of Japan who now is on the top U.S. pairs team with John Baldwin, recalled trying the jump until her body was bruised.

“It was something only (Ito) could do,” Inoue said. “To me, it’s not something you can learn. You almost have to have it naturally.”

Amber Corwin, who will compete for the senior women’s title at the State Farm U.S. Figure Skating Championships at the Rose Quarter, broke her ankle while trying to master the triple axel a few years ago. She dropped the jump from her program.

“The axel demands tremendous strength,” she said. “I think it definitely has to do with the way you’re built.”

Ito and Harding had the right build — short, strong, with big quadriceps. They also had the right mental makeup.

“The reason Tonya could do it was, she was so strong. She was so strong as an individual,” said Dody Teachman, who coached Harding when she learned and landed the triple axel. “And in her head, as we all know … she was a take-the-bull-by-the-horns kind of girl. If somebody said, ‘You can’t do that,’ she said, ‘Oh, yes, I can.’ “

Ito first landed the jump at the 1988 Aichi Prefecture championship, then did it again at the 1989 world championships. The jump wowed the judges as much as it did the fans. And Ito used the Axel as a psychological weapon.

The next year, Teachman and Harding were together at the 1990 NHK Trophy in Japan, where Ito also was competing. Ito didn’t do the triple axel in the practices leading to the event, and Harding and Teachman figured they were safe not trying to insert the jump into Harding’s routine.

The U.S. skater and her coach were at the side of the arena during the warmup before the women’s free skate as Ito skated past and launched a single axel.

“The (rink) barriers were very high, and her feet crested the barrier. She was easily three or four feet in the air,” Teachman said. “She went around and did a huge double axel. Tonya was standing at the barrier, watching. Midori skates around, does a huge triple axel. Tonya looked at me and said, ‘She can’t do that.’

“I said, ‘She just did.’ Tonya came home and decided it had to be in her program.”

Harding said she first landed a triple axel when she was 12. As a skater, all she wanted to do was jump.

“I hated doing the spins, I hated doing the footwork — even though I was good at them,” Harding said. “But I loved the jumps. The jumps are what made me.”

Harding attacked the triple axel straight on, on a straight edge. Some skaters try to sneak a little early rotation by starting the jump on an edge, Harding said.

Harding’s choreographer, Barbara Flowers, added the jump early in Harding’s 1991 free skate program to music from “Robin Hood.” Harding trailed Kristi Yamaguchi going into the free skate at the U.S. championships, and she fell hard while attempting the axel in warmups.

“I wasn’t scared,” Harding recalled. “I wanted to go out and show everybody. That’s the way I competed. Skating is a luck sport. You can go out and be perfect every day of the month — and you can go out in front of the judges and the fans and … forget it.”

Harding opened with a triple Lutz, then glided down the ice.

“In my setup, I’m thinking, ‘Yes, I can. No, I can’t. Yes, I can. No, I can’t.’ And then I was, ‘Yes, I can,’ and, boom, I did it.”

Teachman leapt, screaming. Flowers tried to keep them both steady. Harding still had most of her program to complete.

Harding completed her triple-triple jump combination and almost blew the landing. She whooshed by Teachman. “Breathe,” the coach shouted.

Harding went into a footwork sequence.

“I’m trying to be pretty, and I’m not pretty,” Harding recalled. “I never was a pretty skater. I’m trying to do the middle finger to thumb, trying to be pretty, and my legs were just shaking.”

But Harding made it through the program. She beat Yamaguchi and earned one perfect 6.0 in technical merit — the first awarded to a U.S. woman in 18 years.

Harding landed the jump again at the 1991 worlds, where she was second, and again at the 1991 Skate America. But she fell on the axel at the 1992 U.S. championships.

Harding tried the jump again in the 1992 Olympic Games free skate when she was battling Ito for the bronze medal — and fell.

Ito, who was trailing Harding, landed a triple axel early in her program. Then she threw in another near the end of her program, an unheard-of physical demand when her body already was depleted. Ito finished second. Harding was fourth, behind Nancy Kerrigan.

“Who the hell does that?” Harding said, laughing at the memory. “She knew if she didn’t do it, I was going to beat her. She was at the end of her program, and (she) did it. But that day, the best girl won.

“To me, Midori was my only competitor. She was like me. Short, stocky legs. Guts. Determination. The power.”

Ito’s was the last triple axel landed by a woman until Nakano and Nelidina in 2002.

But the jump could become more common with new training techniques.

The triple axel has defied almost every woman who has tried it. But not Harding.

“Most girls don’t have the strength or the guts to do it,” she said.

“And that’s all I have to say about that.”