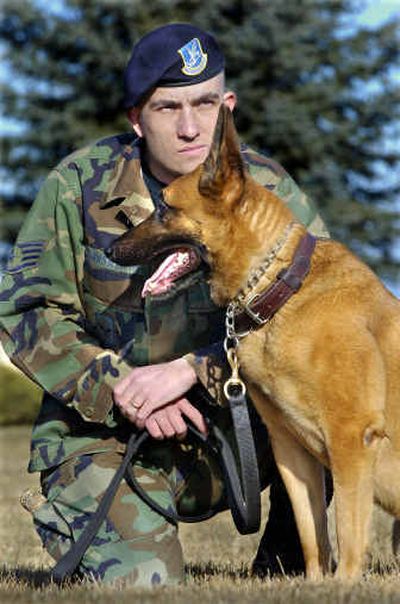

A nose for sniffing out explosives

Eesau, the Belgian Malinois, sniffed out explosives four times during his recent tour of duty in Iraq, said Staff Sgt. Joshua Farnsworth.

Together, the Air Force bomb-sniffing dog and his handler probably saved some lives over there.

“I’d like to think so,” said Farnsworth, a member of the 92nd Security Forces Squadron based at Fairchild Air Force Base. The pair recently returned from Iraq, where “improvised explosive devices” seem to take U.S. or Iraqi lives almost daily.

The K-9 team found something each time they went out on patrol with the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force. Usually it was a cache of guns or ammunition, but they found an IED once and the materials for making bombs three times, Farnsworth said.

Exactly where and when Farnsworth, 30, and Eesau, 4, served in Iraq is classified by the Defense Department. While they were there, the two ran point for the Marines to make sure there were no hidden explosives on the road ahead.

Back in the United States, they are part of a 10-person, 8-dog team commanded by Capt. Phillip Holmes. Fairchild’s dogs are either Malinois or German shepherds. They are bred for this work and trained at Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio from the time they are 12 weeks old, said Tech. Sgt. Charles Wilds, the unit’s senior noncommissioned officer.

At 1½ years, the dogs are put on an odor, he said. Two of Fairchild’s dogs are trained to sniff drugs and six sniff explosives.

“Humans can smell pizza,” Farnsworth said. “Dogs can smell out each ingredient on that pizza.”

Whether the 92nd’s dogs can sniff out cocaine or dynamite, they all are trained in aggression and to protect their handlers. During a demonstration at the base on Tuesday, Staff Sgt. Jamie Emerson simulated the abduction of a criminal suspect with her dog, Lucky.

The Malinois detained the “suspect” by locking his jaws on the man’s padded arm. There was no shaking the dog off. The harder the man tried, the tighter Lucky clamped down. The dog’s aggression matched the suspect’s resistance. Then, at Emerson’s command, Lucky led the man back to the handler’s vehicle.

“Obedience is the foundation of everything we do,” Wilds said.

With the world the way it is today, he said, these dogs are more and more in demand. They and their handlers are deployed all over, working for such agencies as the Secret Service, the Department of Homeland Security or the Federal Protection Service.

They can be found at sporting events such as the Super Bowl or at ports of entries. They spend more time away from Fairchild than on the base, Wilds said. The dogs can work as long as 10 years.

Many Iraqis, because of cultural differences, are afraid of the dogs, Farnsworth said, but others felt safer knowing that where Eesau was there probably were no bombs.

Farnsworth spent four years in the Marines as a military police officer before finding a home in the 92nd Security Forces.

“There’s nothing I’d rather be doing,” he said.