Death reopens wound

Another big game hunting season has drawn to a close, and among the harvest was one unintended death – that of a hunter mistaken for a deer.

When Mary Seppala heard about the Nov. 27 death of Casey Lawson, a 30-year-old man from the Spokane Valley, she said it broke her heart.

“There’s no excuse for shooting something when you don’t know what you’re shooting at,” said Seppala. “It’s just not OK. The law needs to be changed.”

She means the law that allows big-game hunters to go in the woods without wearing hunter orange – as they must in Washington and most other states. And she also means laws that don’t bring maximum penalties against people who shoot people.

In one Idaho case last year, the man who nearly killed hunter Bruce Jensen spent four months in jail, was fined $363.50 and was put on two years probation after pleading guilty to careless discharge of a firearm.

“Too many lives are being lost and too many people are being hurt,” Seppala said.

She speaks from personal experience. Her husband, 43-year-old Steven Seppala of Ponderay, Idaho, was killed last year in a hunting accident near Avery, Idaho.

One difference between the deaths of Lawson and Seppala is authorities have a man in custody who they think shot Lawson.

Raleigh Paul Turley, 24, of Hayden has been charged with involuntary manslaughter for shooting Lawson. If convicted, he could face up to 10 years in prison.

Mary Seppala is still waiting for the person who shot her husband to either turn himself in or be caught.

“Somebody knew what they did,” Seppala said. “They walked up, they saw he wasn’t moving and they left. It was 30 yards. Whoever did it walked away. They weren’t responsible. They didn’t care. That just makes me sick.”

Neither Lawson nor Seppala was wearing hunter orange. In Lawson’s case, however, the shooting occurred after dark – a violation of state law, and one way to render hunter orange irrelevant.

And while Mary Seppala has become an advocate for a hunter orange law, to blame her husband’s death on what he was wearing strikes her as blaming the victim.

Although every situation is different, statistics tend to support hunter orange as effective in preventing two-party hunting accidents.

Idaho has had 50 fatal hunting accidents since 1979, an average of fewer than two a year. Before that, “it was slaughter row,” said Kootenai County Prosecutor Bill Douglas. For instance, in 1970 alone, there were 10 fatalities.

In nearly every fatal case, the victim was not wearing hunter orange. The exceptions in the last 27 years are one hunter who accidentally shot himself, another victim who was completely out of sight of the shooter, and a third victim who was wearing an orange hat, but a blue and green coat. The latter victim, in the orange hat, was the only one mistaken for game.

Most hunter orange laws around the country – including Washington’s – require a minimum of 400 square inches visible above the waist from all sides. Deer and elk are color blind, and do not see orange, biologists say.

According to Ron Fritz, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game hunter safety coordinator, a study in New York from 1992 through 2001 found that out of 580,000 hunters who wore hunter orange, none was killed, while 18 hunters out of 120,000 not wearing hunter orange were killed.

Still, getting a hunter orange bill passed in the Idaho Legislature has been an exercise in futility for folks like Douglas and Shoshone County Sheriff Chuck Reynalds, who made a run at it last year after Seppala and Jensen were shot in his county.

“I attempted to contact legislators to carry a bill for hunter orange,” Reynalds said. “I received no support for that. Zero.”

Douglas couldn’t find a legislator interested in 2000, either, because some members of the Idaho Fish and Game Commission were opposed, he said.

The closest hunter orange got to state law was in 1988, when a bill was defeated on the House floor, 29 votes in favor and 51 against, said Roger Fuhrman, Idaho Department of Fish and Game spokesman.

He explains the opposition’s sentiments this way: “One of hunting’s greatest attractions is a sense of freedom.”

Nonetheless, the department this winter plans to survey the 5,000 hunters it has on an e-mail list to gauge their opinion. The commission asked for the survey after last year’s rash of accidents, when it again discussed making hunter orange a requirement, Fuhrman said.

Seppala said it wouldn’t take long for legislators to back the bill if they lost a loved one in a hunting accident.

“I have two daughters who are never going to heal from this, just like I’m not,” she said.

She plans to lobby for a hunter orange law, but for the past year she’s been too busy trying to solve the mystery of who killed her husband on Oct. 16, 2004, near Avery.

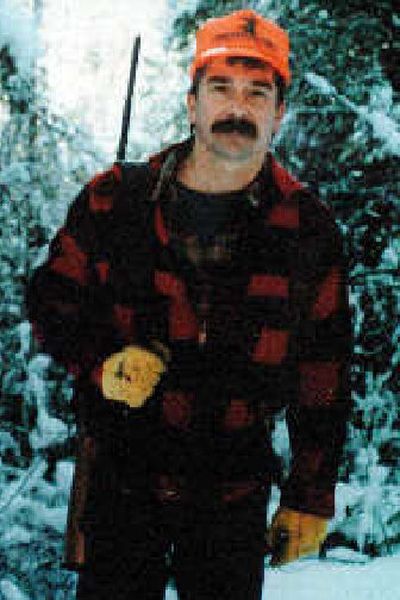

It was the first day of the season for Steven Seppala, who went out hunting with four family members. The Shoshone County Sheriff’s Department seized the guns of the entire hunting party, and each member of the party submitted to polygraph tests.

They all passed, but while the Sheriff’s Department and Seppala’s widow suspect a particular member of the hunting party, they have no confession or hard evidence.

“This has torn our family apart,” Seppala said.

A search with more than 60 volunteers and law enforcement officers last summer of the area turned up nothing, but Seppala returned this October with two men and a metal detector. They found a bullet with fiber and flesh 36 feet from where her husband was found.

The bullet is now at a state laboratory, awaiting DNA testing.

If the bullet isn’t the one that killed Seppala or if it doesn’t match any of the hunting party’s guns, “I’m at a dead end in this case unless somebody comes forward,” said Undersheriff Mitch Alexander.

Even those who turn themselves in shouldn’t get off easy, said Diana Jensen, whose husband was shot near the St. Joe River last year.

“My husband almost died on the mountain,” said Diana Jensen. “If the bullet would have been an inch one way, he would have bled to death. An inch the other way, he would have been paralyzed.”

As it was, Bruce Jensen’s hip was shattered and he couldn’t work for six months. The couple nearly lost their home and vehicle.

Jensen was wearing camouflage, because he was headed to an area for muzzleloader hunting, where hunters need to be in close proximity to shoot and kill game. Diana Jensen said he was walking in ankle-high vegetation, in full view of the shooter, David E. Spicer of Caldwell, Idaho.

She thinks Spicer’s penalty was too light.

“If somebody shoots a bull moose, it’s a huge $10,000 fine. They get hung, they lose their license and everything,” she said. “But you shoot a man? I don’t think the penalties are stiff enough.”