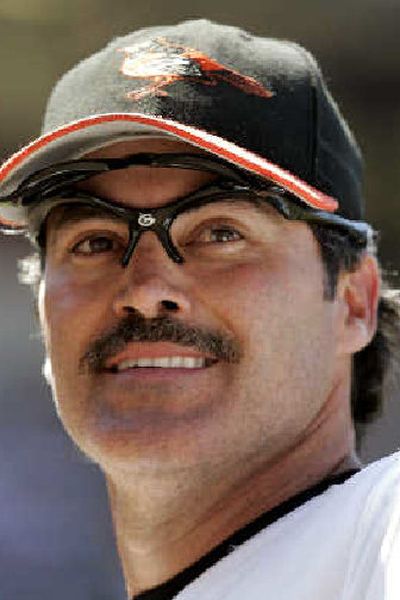

Palmeiro’s supporters await valid explanation

CHICAGO – Rafael Palmeiro asked us to give him the benefit of the doubt, but didn’t say why we should.

That Palmeiro didn’t say how banned substances had found their way into his urine made it hard to believe his defense, even before the New York Times reported he had tested positive for Stanozolol, seconding the Chicago Tribune report that a “serious” steroid was involved.

Even Palmeiro’s fellow players found it odd that he said he hadn’t done anything wrong yet declined to offer an explanation. If he had taken a banned substance unintentionally, as Gary Sheffield said he once did, he should have named it.

“I can’t speak for him,” Sheffield said. “But that’s how I would have handled it.”

That is exactly what Seattle pitcher Ryan Franklin did last week, making his claim of innocence at least somewhat believable – although it doesn’t help that he’s the second Seattle player suspended, and the 10th from the organization.

Franklin, who was suspended for 10 days one day after the Palmeiro bombshell, gathered reporters together in a small room near the visitor’s clubhouse at Detroit’s Comerica Park and pleaded again the case he had lost with the commissioner’s office and arbitrator Shaym Das.

He said he has no idea how he could have tested positive, because the only things he has taken are two supplements – a protein shake and a multivitamin, both available over the counter – that came back negative for banned substances when they were tested.

“Until the day I die, it’s hard for me to believe,” Franklin said. “I was one of the guys that was always supportive of stronger testing. It’s just kind of hard to swallow. … The testing has to be flawed, or my urine got mixed up with somebody else’s. They said that couldn’t happen. But I don’t believe it. I know deep in my heart that I’d never do anything like that.”

Maybe it’s possible for a false positive to slip through the system or a players’ urine to get mixed up with another players’ sample. But in the current climate, in which all players seem to be under a cloud of suspicion, players cannot believe that someone as prominent as Palmeiro would think he could beat the system.

“Whether or not you’ve done anything in the past, you would think that this year, you’d take extra precautions to make sure you didn’t do anything,” Kansas City first baseman Mike Sweeney said. “You wouldn’t even want to pull into a GNC parking lot.”

When Palmeiro wagged his finger and told Rep. Tom Davis, R-Va., that he never had taken steroids, period, he confirmed the beliefs of a lot of people who thought they knew him well. That list included former Rangers owner George W. Bush and lots of others in Texas, where he blossomed into a slugger while playing alongside Jose Canseco in 1992-94.

Cincinnati Reds manager Jerry Narron, who served as Johnny Oates’ third-base coach in those days, was stunned by Palmeiro’s suspension.

“None of us know all the facts, but I’m disappointed, for sure,” Narron said. “He is one of the guys I would say wasn’t using steroids. … I remember going to the ballpark in November and December and he’d be there, nobody else around, hitting in the cage. And I remember him working hard after games, late at night.”

Before Palmeiro’s suspension, Minnesota reliever Juan Rincon was the most prominent player who had tested positive for a banned performance-enhancing substance. He hasn’t heard much about it since serving his 10-day suspension.

“You go to a town, and people don’t know your name,” Rincon said. “But Palmeiro, I’m pretty sure they know his name.”

Palmeiro sometimes trains in the off-seasons with another player suspended this season, Colorado Rockies outfielder Jorge Piedra. He said they never discussed steroids.

Piedra doesn’t expect Commissioner Bud Selig to succeed in his attempt to “eradicate” steroids from baseball.

“People in all facets of life are always looking for an edge,” Piedra said. “In business or sports, people look for ways to get ahead. There will be temptations that are in that gray area, and some people will fall for them. That’s life.”