His death paves way for helping other children

About half the kindergartners at Willard Elementary School on Spokane’s North Side have lost one or more of their baby teeth.

In one kindergarten classroom, every time a child’s tooth falls out, teacher Joy Baird places a giant paper tooth on the Tooth Graph to commemorate it. In the other kindergarten classroom, teacher Susan Nunley has posted a poem from the Internet that reads: “Yesterday I lost a tooth when I ate a lime. The tooth fairy came last night and she left me a dime.”

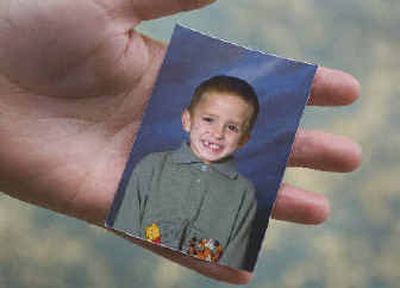

In a photo we published recently of Tyler Joseph DeLeon, the 6-year-old kindergartner is missing two of his top baby teeth. Tyler died Jan. 13, his seventh birthday, under circumstances that are still being investigated. His adoptive mother and her daughter are under suspicion in the death, according to the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office. Tyler weighed 33 pounds when he died, less than a chubby toddler, and Child Protective Services had on record reports of suspected abuse. They didn’t investigate those reports for nine days.

In part because of Tyler’s death, major policy changes were announced last week by Gov. Christine Gregoire. Now, after a report of suspected abuse, caseworkers must make investigative visits within 72 hours; 24 hours if the threat to a child appears imminent.

So Tyler’s death has reaped some permanent benefits for other children, though he didn’t live long enough to experience his own permanent teeth.

Monday, because I couldn’t ask Tyler, I asked four classes of kindergartners to tell me about losing their baby teeth. They eagerly complied. I was at Willard doing writing workshops as part of a school outreach by organizers of the regional literary festival Get Lit!

The kindergartners were 5 and 6. They told me they like how it feels in their mouth where the missing teeth once were. They like to wiggle their loose teeth. They love the tooth fairy money most of all, and they think it’s neat to have a couple of holes in their smiles.

The three kindergarten teachers I met Monday beamed as their students talked teeth with me. The teachers – Baird, Nunley and Andrea Sims – have those great kindergarten-teacher voices, soft yet firm. They have incorporated kindergarten rituals that anchor these small ones into community. Every day, the children salute the flag. Every day, they write on a board the date and the weather. Monday, it was sunny.

When they passed around a basket of markers to write with, rather than argue over who got which color, they chanted this reminder: “You get what you get and you don’t throw a fit.”

They thanked me for their writing lessons by opening their mouths wide and saying a silent “wow!” Lots of teeth were missing in that Giant Wow, as this gesture is called.

As I watched these gentle kindergarten teachers at Willard, I felt sympathy for the teachers and staff at Tyler’s school, Lake Spokane Elementary School. They tried to seek help for the child who they said looked like a ragamuffin. They reported Tyler’s bruises to the authorities. But nothing happened. And then, he was gone.

In every school, people look out for the littlest ones. Even the older students will speak in kinder, “inside” voices in the halls where 5- and 6-year-olds gather.

“In September, they come in so young, often literally rolling on the floor, and in June, they leave ready for first grade. No other grade sees so much change,” said teacher Baird.

The kindergartners at Willard told me that if they could plant their baby teeth in a garden, they could grow miraculous things: a tooth flower, a money tree.

I would plant some baby teeth in a garden, too, with this wish: that every child Tyler’s age would be surrounded by kind adults who place on a graph the story of their lost baby teeth or post tooth-fairy poems on walls or leave dimes under pillows. And this wish, too: That every child would be treated like a Giant Wow.

These wishes are as fanciful as growing tooth flowers from baby teeth. I know this, but still, in Tyler’s memory today, I wish it anyway.