Bombing plotter”s assistance crucial to anti-terror work, prosecutors say

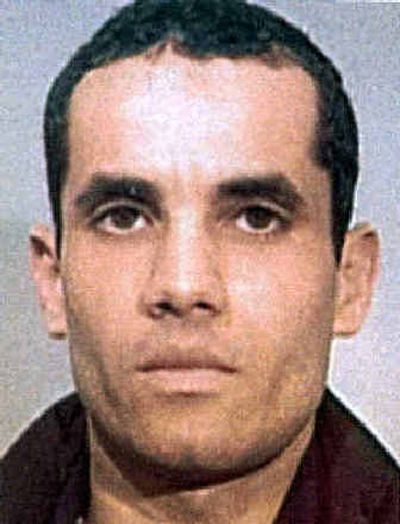

SEATTLE – Five years after being arrested at the U.S. border with a trunkful of bomb-making materials, Ahmed Ressam has proved an unparalleled resource in the country’s efforts to understand and eradicate terrorists.

He told investigators from many countries about the locations of terror cells and camps, who ran them and how they operated.

But as Ressam, 37, awaits sentencing today, prosecutors say he could have done more.

Ressam, an Algerian convicted of plotting a millennium-eve bombing at the Los Angeles airport, stopped cooperating with prosecutors in 2003 when he realized the Justice Department wouldn’t recommend a sentence shorter than 27 years, the prosecutors say.

Without his continued help, prosecutors fear they will have to drop terrorism charges against two men: Abu Doha, who was accused of orchestrating the bomb plot, and Samir Ait Mohamed, also charged in the plot.

“We would not consider dropping such critical charges unless his cooperation was found to be severely lacking,” said First Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Bartlett.

The government is seeking 35 years. Ressam’s public defenders, who say his assistance has been unique in the war on terrorism, are recommending 12 1/2 years.

A psychiatrist who evaluated Ressam blamed the government.

Officials took months to get Ressam out of solitary confinement when his mental condition began to deteriorate and he became less responsive, Dr. Stuart Grassian said.

“If these problems developed and hardened during a period of stringent confinement, the sooner we got him out of there the better,” said Grassian, who taught for nearly three decades at Harvard University Medical School.

“We wanted him to be away from that to allow his mental state to soften again.”

Ressam was arrested in Port Angeles, Wash., in December 1999 as he drove off a ferry from British Columbia.

Customs worker Diana Dean noticed Ressam seemed nervous. In his car trunk, agents found explosives more powerful than TNT and digital watches that could be used as timers.

Ressam was convicted on explosives charges and conspiracy to commit international terrorism in April 2001.

Facing as much as 130 years in prison, Ressam began to sing. Prosecutors say he wanted to reduce his sentence, but Grassian argues it was more complex. The government was offering Ressam, a poor Algerian who had been kicked out of several countries, the same thing Jihadi extremists had: a sense of self worth and a connection to a cause.

Over the next two years, in meetings with international investigators, Ressam offered details about various terrorist operations, according to court documents filed by his lawyers.

He provided information on more than 100 potential terrorists and testified against co-conspirator Mokhtar Haouari and Sept. 11 plotter Mounir el-Motassadeq. Ressam first told investigators about the type of shoe-bomb Richard Reid attempted to use on a flight to the United States. And, his lawyers say, Ressam helped save lives by providing information about a network of Algerian terrorists operating in Europe.

But in 2003, Ressam stopped talking. Grassian recommended in November of that year that Ressam be moved from solitary confinement. Ressam was frustrated, Grassian said, by repeated interrogations. He was forced to repeat earlier testimony, nuances were lost in translation, and he felt pressured to confirm statements he did not believe he had ever made, Grassian said. According to Grassian, Ressam wasn’t moved until June 2004; prosecutors say he was transferred two months earlier.

Bartlett noted prosecutors first offered to move Ressam from solitary in March 2002, but Ressam, who reportedly feared the alternative, refused. And in the months since Ressam was taken from solitary, his cooperation has not improved. On Feb. 25, prosecutors questioned Ressam once more in a last-ditch effort to salvage the cases against Doha and Mohamed.

“For the most part, Ressam answered that he did not know or did not recall the answers to the questions,” federal prosecutors from New York wrote. “The government believes that Ressam lied and that his answers reflect a refusal to continue cooperating.”

Dean, the agent who helped catch Ressam, has retired to North Dakota, and an annual customs employee award has been named in her honor. For her, the sentencing is the final chapter in Ressam’s saga.

“I just hope justice is done and they give him what he deserves to get,” she said.