Whole corps helped raise Baby George

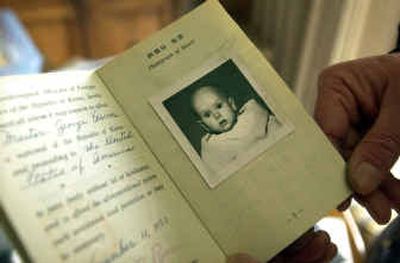

It took Ted Brothers 52 years to find out what happened to Baby George.

But the decades and miles that divided them seemed to melt away this month when Brothers traveled to Spokane to meet Daniel Keenan – an orphan abandoned in Korea who was saved by U.S. soldiers and brought to the United States.

“There’s no question I would have died there without your help and the aid of so many members of the American military,” Keenan told Brothers when the two men met April 13 in Spokane. “It really did take a village to raise me.”

Brothers last saw Keenan in the summer of 1953 when he was a blue-eyed Amerasian infant at an orphanage in Inchon, Korea. The week-old baby boy had been abandoned – sick, emaciated and wrapped in filthy rags – outside an Army Service Command Post, ASCOM.

“I always wondered if you made it,” said Ted Brothers, 77, of Lake George, N.Y., a Marine Corps engineer during the Korean War. “You were just a runt way back then, and look at you now. What a rare privilege this is. It gives me goose bumps.”

As a blue-eyed, mixed-race newborn, “Baby George ASCOM” was shunned by Korean nurses in a war-torn country short of food and clothing, with orphanages bursting at the seams and barely able to cope with scores of their own children orphaned by the war.

U.S. military personnel took up the baby’s cause and helped him become the first Korean War orphan adopted by an American couple and brought to the United States.

Keenan was adopted by Lt. Hugh Keenan, a U.S. Navy surgeon stationed aboard the hospital ship USS Consolation at Inchon in 1953. Keenan and his wife, Genevieve, had two daughters but had lost three baby boys at birth. The family lived in Spokane.

Today, Daniel Keenan is a 51-year-old social worker who works with mentally ill adults. (He also works occasionally as a sports correspondent for The Spokesman-Review.) Although he doesn’t know his exact birth date, he celebrates it as May 30. Keenan, the father of two grown sons, lives with his wife, Shirley, a retired court administrator, in an apartment in Browne’s Addition.

At the time of his arrival in Seattle on a Navy ship shortly before Christmas in 1953, the Keenan baby was a momentary celebrity, featured in Newsweek and other publications.

“That was my 15 minutes of fame, and then I lapsed into a life of rightful anonymity,” Keenan said with a chuckle.

Brothers never saw the stories, and for 52 years he carried a black-and-white snapshot as a kind of talisman. He hoped the photo might one day reveal its mystery about a bright, hopeful moment in an otherwise dark conflict. In the picture from late summer 1953, a few weeks after a cease-fire was signed, an infant is cradled by a Catholic nun.

Brothers and his Marine Corps buddy Al Moreno beamed as they posed alongside Sister Philomena and the baby in front of the Star of the Sea Children’s Home, an orphanage in Inchon. The men had just delivered supplies to the orphans that Brothers’ mother had gathered and shipped from Virginia.

Marines had discovered the infant, bathed and fed him, and brought him to Sister Philomena.

A month later, Brothers was shipped out of Korea. He lost track of the baby boy.

But the incongruity of that forlorn infant being rescued and reared by combat-hardened American soldiers continued to stir in Brothers’ heart long after he left the war zone.

“Over the years, if anything reminded Ted of Korea, he’d tell me the story of Baby George ASCOM over again and wonder what ever happened to him,” said Noel, his wife of 44 years. After the war – when he earned the nickname “Boom Boom” Brothers for his demolition skills as a Marine Corps engineer – he worked on large bridge projects around the country.

Brothers later was ordained as a Presbyterian minister. The couple spent several years at a parish in Portugal, where they raised three children. In retirement, he’s built sailboats, restored an Adirondack guide boat and translated a religious text by a Portuguese minister.

Last month, 52 years after leaving Korea, Brothers reached Keenan by telephone in Spokane after locating him through an Internet search. They planned the Spokane reunion.

After being reared by Sister Philomena at her orphanage, the baby boy was taken aboard a Navy escort carrier, USS Point Cruz. There were better medical care and supplies on the ship than in the orphanage, where Korean nurses shunned the infant despite Sister Philomena’s pleas. Aboard the ship, sailors prepared a nursery, built a crib and playpen, fashioned diapers out of sheets – and thoroughly spoiled the baby.

They made toys, fussed over him and took turns wheeling the infant they called “Baby-san” around the deck in a bomb cart converted into a baby carriage. The baby thrived under the Navy men’s care.

Keenan’s story was told in a 1997 made-for-TV movie, “A Thousand Men and a Baby.”

Keenan has collaborated on a book, “The Navy’s Baby,” with author Janet Matthews, who lives in Toronto. She included a brief version of his story in an earlier book, “Chicken Soup for the Parent’s Soul.”

This all came as news to Brothers.

“I could only picture this little baby at the orphanage, and it was remarkable to see the fine man he has become,” Brothers said.

Brothers said the orphaned baby taught him the blessing of new life in the midst of Korea’s killing fields.

“The sad truth is that the happy ending to Daniel’s life was a roll of the dice,” Brothers said. “What made this story stick with me was that there was an island of humanity amid the killing because of the dedication of one nun.”

Investigations by the Navy into Keenan’s provenance shortly after the infant was discovered were inconclusive.

“I’ve interviewed a lot of the Navy vets who helped raise Dan on the Point Cruz and it’s always an incredibly emotional moment when they reconnect with him,” Matthews said. “One of them put it to me this way: ‘As surely as we saved him, he saved us.’ “

“Helping that baby symbolized the best part of these men, some of whom had babies of their own back home,” Matthews said. “By saving a life, they felt it somehow balanced out the killing they had done.”