Creatine not magic potion, but can be used safely

Diligent training and proper nutrition are the foundation of success for high school athletes.

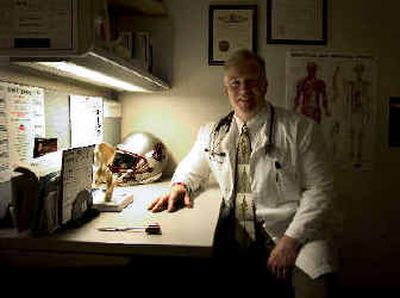

But creatine, said Daniel Dami, Ph.D., can enhance that foundation if an athlete already works hard, eats right and will use the muscle-building supplement properly.

Dami, a physicians’ assistant in family medicine at Rockwood Clinic with an emphasis on sports medicine, is backing his opinion with action, monitoring the creatine use of his hard-working stepson, Skylar Jessen.

“Taking a look at all these different studies, I have never found (one) that said if creatine was taken at a proper dose, with the proper amount of water, within certain cycling episodes, there was any major side effect,” said Dami, who is also a volunteer medical director in the Eastern Washington University athletic department and wrote his Ph.D. dissertation on creatine. “Even the minimal side effects, like cramping, GI (gastrointestinal) distress and headaches, are directly related to lack of water consumption or overdosing of creatine by athletes.”

In a nutshell, creatine is a nutrient found naturally in the body and in foods such as red meat. It helps with short bursts of high-energy output, not aerobics. Bolstering the small amount of natural creatine with a supplement gives an athlete quicker recovery time of energy to muscles and for rebuilding muscles.

It is also found on the shelves of nutrition stores and lockers of many high school athletes.

But before running out to purchase creatine for your budding superstar, it would be best to reread the first paragraph and hear what else Dami had to say. The emphasis is on eating habits and work ethic.

“Ninety-nine percent of the kids, when you start talking to them about what they’re eating and how they’re lifting, are not doing it right,” said Dami, who hopes to have an article on the subject printed in a medical journal in the next year. “If you just change that, they will have so much more of a gain than adding creatine to their regimen right now.”

Once an athlete makes that commitment, Dami still isn’t giving a blanket endorsement to creatine use.

“When kids talk to me, I always tell them if you really want to start discussing this you need to bring your parents in with you,” Dami said. “I would never consider it before the age of 16 for anybody. Some kids I wouldn’t recommend it before the age of 19. That’s why medical professionals need to be brought in.”

The athlete must be done with his/her main growth spurts and have completely healthy internal organs, Dami continued. Parents also need to understand there are no long-term studies on possible effects of creatine use.

“Right now it looks pretty favorable,” Dami said. “There is the possibility of risk, but the risk is going to be low if they follow directions exactly.”

The Washington Interscholastic Activities Association and the Greater Spokane League, among other entities, advise coaches to stay out of the supplement business.

“We have had specific discussions about creatine and that sort of stuff,” GSL secretary Randy Ryan said. “We emphasized that stuff is not to be recommended by coaches or promoted at all.”

That’s not a hard sell to coaches who know the work ethic and nutritional habits of most teenagers but don’t know the long-term implications (read liability) of creatine.

“We suggest against it here. Although, since it is legal, there’s really nothing you can do,” Mt. Spokane football coach Mike McLaughlin said. “We don’t counsel our kids to use it, but I’d be very naïve if I said none of our kids in the past have used it because I’m sure they have.”

When his son was playing for him, McLaughlin researched creatine and decided against it. But he is convinced that some schools promote creatine use.

“I wonder, if you’re not 100 percent sure what that is doing to your son’s or daughter’s body, how can you do it?” Lewis and Clark football coach Tom Yearout asked.

“I don’t encourage it,” Mead football coach Sean Carty said. “I’m a nutrition and fitness teacher. I teach fruits and vegetables and meats. If kids would just sleep the number of hours they’re supposed to and eat healthy foods, they would be fine.”

That being said, Carty added, “We have kids doing creatine. I just try to warn them about the risk. There are no studies to support how safe they are in the long run.”

One of the Panthers who uses creatine is Dami’s stepson, Jessen.

“My conflict is how much do I argue with a guy that knows more than me,” said Carty, a powerfully built and avid weight lifter. “I don’t push it and I don’t subtly say it’s OK. I don’t use anything and I won’t use anything. That’s my message. But I don’t tell parents what they can and can’t do. I’m not going to blackball them or fight them on it because they’re legal.”

Dami, who has researched hundreds of articles on the subject, said close monitoring of athletes using creatine is essential. Creatine doesn’t work if the athlete isn’t working out. Increasing the amount of creatine beyond the recommended dosage doesn’t increase strength. And besides eating and sleeping properly, a 170-pound athlete using creatine needs to drink 100 ounces of water a day. Only then will a young athlete get the benefits of creatine.

“Bottom line, my passion is to help kids,” Dami said. “I want to make sure nothing goes out to cause any kind of harm to those kids.”