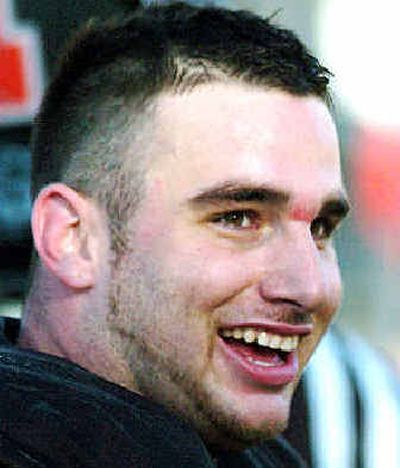

Back on line

Chaney Kogel-Stobart becomes emotional recalling the accident, particularly the point when the Ford Explorer finally stopped rolling and she looked over at the empty driver’s seat. That’s where her son, University of Idaho football player Andrew Stobart, had been sitting before the vehicle hit a patch of black ice on State Highway 26 just west of Othello on Dec. 26, 2003.

“For a fleeting second I thought, ‘Where did he go?’ ” she said. “Is he out looking for me? All of a sudden, I couldn’t breathe, my arm was stinging and I could hear him in a field. I looked to my right and saw him. I saw dust or something like he had just landed.”

Stobart had landed about 60 feet from the car after he went flying through the windshield. He wasn’t wearing a seat belt, but he figures that might have saved his life because the roof on the driver’s side caved in during the accident.

“I stuck the landing on my feet,” Stobart said. “I just started walking back toward the car.”

By that time, Kogel-Stobart had broken a window and crawled out into the chilly morning air. She saw something wasn’t right with her son.

“If the car would have been running, Andrew would have got back in and gone, that’s just the way he is,” she said. “But he was very pale and his left foot was very swollen.”

That wasn’t the worst of it. Stobart, it would be soon be discovered, had broken two vertebrae in his back and by the time he was transported to the hospital he was suffering paralysis.

It wasn’t the diagnosis a football player wants to hear. Or ex-football player, as some doctors and nurses told Stobart in the days and weeks after the accident. Stobart banned one nurse, who said he would never play football again, from his room.

Spokane neurosurgeon Dean Martz inserted two nine-inch rods connected by a bridge and eight bolts, and fused several vertebrae in the middle of Stobart’s back. After nine days in the hospital, Stobart returned to Moscow. Kogel-Stobart lived with her son for more than a month to care for him.

“Dr. Martz never told me no and it was one of the reasons I really liked him,” Stobart said. “He never told me no and he never told me yes. I would talk about football and tell him, ‘I’ll get you tickets,’ and he would be like, ‘Good, I’d love to go.’ “

To provide some insight into Stobart’s attitude, he believed he could return last season, roughly eight months after the accident. To this day, he’s certain he could have played the latter half of the 2004 season. Doctors had other ideas and didn’t clear him until February, 2005, but Stobart’s rapid recovery still has some in the medical community scratching their heads.

Stobart was supposed to be in a back brace for four months. He took it off in four weeks. He was playing basketball within three months and dunked in the fourth month. By five months, he was lifting weights.

“He was the first guy I met when I got the job,” defensive line coach James Cregg said. “I’m thinking, ‘This is one of your better linemen.’ Here he was in a shell, had his brace on, but once you get to know the kid, you realize he was determined to come back. It’s been unreal.”

Two months ago, Stobart told head coach Nick Holt he would be absent from the team’s daily conditioning workout because he had an appointment with Dr. Jens Chapman in Seattle to see if he could receive clearance to play.

“He (Holt) said, ‘Do you really think you have a chance at coming back?’ ” Stobart said. “I said, ‘Are you doubting me?’ From a coach’s perspective he didn’t believe it.”

Stobart’s progress stunned Chapman, who had declined to clear Stobart in February 2004.

“His jaw nearly dropped and hit the ground,” Stobart said. “The only thing he could do was shake my hand and he said he’ll be at the UW game (on Sept. 17).”

Stobart has released his medical records so Chapman, who specializes in spinal trauma, can study his recovery. Attempts to contact Chapman and Martz were unsuccessful.

Stobart is the first to admit he didn’t exactly follow doctor’s orders during rehabilitation. “I just based it on how I felt day to day,” he said.

That approach drew occasional lectures from trainer Barrie Steele.

“He pushes the envelope; I gave him a few speeches,” Steele said. “When you’ve got a kid with a lot of hardware in his back, there is an increased concern on my part, but I think we’ve taken the appropriate steps with the appropriate medical people who have granted him permission to play.”

Stobart’s comeback was fueled by his drive to return to football and his mother’s unwavering support.

“All the times I’ve called him crying in the middle of night,” said Kogel-Stobart, who suffered back, neck and thumb injuries in the accident. “If anything he was my rock. He might think I was his, but he was mine.”

Stobart is practically giddy during spring football. He’s seeing time at defensive tackle and end. Holt and Cregg said Stobart will definitely be in the playing rotation this fall. Stobart’s pre- and post-accident weight-lifting numbers are virtually the same and he’s regained the 45 pounds he lost after the accident.

“I’m getting there,” said Stobart, a sophomore who prepped at Borah High in Boise. “My pass rush needs help. I’m not consistent at all. By the end of spring, I should be back to where I was.”

That beats where he was on Dec. 26th, 2003. On his first few trips from Moscow to the Seattle area after the accident, Stobart took an alternate route.

“But you’ve gotta get over it and move on with life,” he said. “So I do (take Highway 26) now. I’ll stop and get all ticked off every time I see the (accident site). Football gave me this entirely different mentality on life. It gets my adrenaline going and I’m willing to fight it.”