Simple pleasures in Mexico

“I’m feeling a little nervous,” volunteered my 13-year-old nephew.

Bobby was standing in the hot white sand of the Mexican Pacific, strapped to a parachute harness. For months, he had been dreaming of parasailing.

Nervous? Even I, who have no kids, knew that teenage males would rather be flogged than admit weakness. Clearly, he wasn’t nervous.

He was terrified.

“I’m sure they have done this lots of times!” I said hopefully.

Then the rope from the speedboat jerked, and Bobby lurched forward a few steps. And suddenly he was soaring over the ocean, a billowing purple and red parachute behind him. Now, only his aunt was nervous.

This was my fifth trip to Mexico with a niece or nephew, a tradition that dated from my time there as a foreign correspondent in the 1990s. I had loved working abroad, but keenly missed my four siblings’ children. So when the oldest finished grade school in Kentucky, my gift was a plane ticket. Soon, the Mexico trip was a rite of passage.

Over the years, the eighth-graders and I had climbed Mayan pyramids and snorkeled in the Caribbean. We had stayed in restored haciendas and ridden horses through Copper Canyon. We had had some mishaps: blistering sunburn, a lost passport, an upset stomach. But each kid had survived to tell the tale.

So far.

Bobby had especially looked forward to his weeklong trip. A gentle, dreamy boy just hardening into adolescence, he had intently studied Mexico. I had always suggested itineraries to my nieces and nephews, but Bobby had his own ideas: to visit Patzcuaro, a beautiful colonial town west of Mexico City. And, above all, to parasail.

Our trip began with a flight from Washington, D.C., to Mexico on a rainy Sunday. Suddenly, Bobby was in an exotic new world, and we hadn’t even left the Mexico City airport yet.

“I’ve never seen one of these before,” said the neophyte traveler, inspecting the moving walkway with satisfaction.

After spending the night with friends, we set off in our rented car for Patzcuaro. The 240-mile route winds through a landscape of soft blue lakes and misty green fields, Mexico by way of Monet. Normally, it takes about five hours by car. But it had been years since I had driven in Mexico City traffic and my combat skills were rusty.

We spent an hour trying to escape the city, then got lost again on the highway. Even taking advantage of the liberal Mexican attitude toward the law – “Auntie Speed Demon!” my nephew crowed – it was evening by the time we limped into our hotel.

Fortunately, Hacienda Mariposas was a delightful place to limp in to. About 7,000 feet above sea level, the estate features upscale rustic cottages nestled in 18 acres of cool, quiet, pine-scented woods.

Ah, nature. Ah, nurture. A margarita instantly appeared at our cabin, courtesy of the house.

As night fell, we repaired to the beamed dining room and, in front of a roaring fire, feasted on that evening’s offerings: calabaza soup, a salad with grapefruit and papaya, and chiles rellenos. To my delight, Bobby enjoyed everything – even after learning that calabaza meant “squash.”

The Mexican-American owner, Rene Ocana, joined us as we finished our apple crepes with caramel sauce, suggesting visits to the charming Purepecha Indian villages around Patzcuaro’s lake, noted for their handicrafts.

But we were keen to explore the huge lake and its main island, Janitzio, which Bobby had discovered on the Internet. So the next morning we headed for the town docks and paid $3 to board a painted wooden launch (decorated with the requisite Virgin of Guadalupe) for the half-hour trip.

Janitzio is famous for its Day of the Dead festivities, which draw thousands of visitors each November. Little known by Americans, the picturesque fishing village lives off domestic tourism the rest of the year, as reflected in the profusion of shops and cafes.

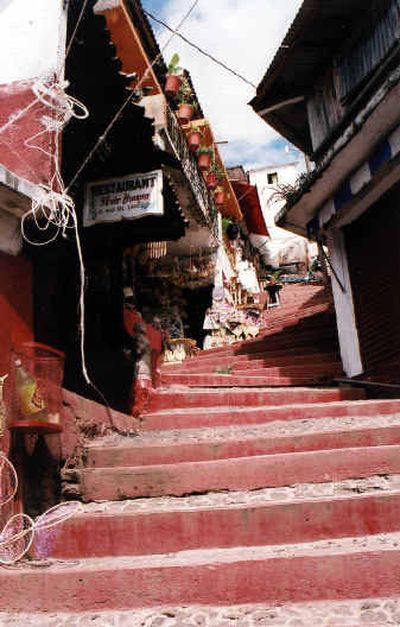

And yet, we were enchanted by the place. With no roads, Janitzio is laced with stone staircases winding past simple, open-air restaurants ablaze with color: turquoise chairs, purple tablecloths, garlands of pink and yellow fabric flowers. Locals sit along the ascent, carving wooden boats or embroidering towels.

We worked our way up the stairs, giggling at vendors offering us plastic cups of fried eels, and arrived at a plaza with a giant statue of independence hero Jose Maria Morelos. Bobby eagerly climbed the 140 steps to the hero’s raised fist, while I contented myself with the views of the crystalline lake.

We felt that we had stumbled into another world, and the spell held on during the boat trip back to Patzcuaro. Passengers offered us candied cactus, and two reedy-voiced mariachi musicians belted out songs of loss and longing. This was the Mexico I loved, a land of color and deep humanity, and I was so glad Bobby could know it, too.

We spent the afternoon strolling the cobblestone streets of Patzcuaro, peeking into 16th-century churches, colonial monasteries and plenty of stores. Bobby usually hates shopping, but even he was intrigued by the fine crafts, copper and embroidery and carved wood. By day’s end, he had mastered a new phrase: “Cuanto cuesta?” – how much?

The next morning, after a hearty dish of chilaquiles, a sort of nachos-for-breakfast affair, we went horseback riding. To my nephew’s dismay, an employee of the hotel, Sixto, walked in front of him, leading his frisky horse with a rope. But what the trip lacked in velocity it made up for in beauty. First we rode through quiet forests, then fields of white wildflowers and finally up a hill to see the shimmering periwinkle lake of Patzcuaro spread out below us, reflecting an endless sky of puffy white clouds.

It was spectacular, and we could have enjoyed Hacienda Mariposas for another week. But the beach beckoned.

Mexico has an excellent (if pricey) system of toll roads, which covered most of our trip south to the resort town of Ixtapa. It was a five-hour journey of dramatic changes, from mountains to the cactus-studded desert and into the moist warmth of the west coast.

Scenery, of course, only goes so far with a 13-year-old. But Bobby had plenty of entertainment on the drive: Dave Barry and me.

Now, it’s tough to compete with Dave. But when Bobby wasn’t guffawing through his books, I had the chance to chat leisurely with him, discovering so much more than I usually did on my quick trips to his family’s home in Connecticut.

I learned that he was fascinated by ancient Greek and Roman history. I learned that he wanted to be a history teacher. He was curious about everything – particularly my travels during a decade as a foreign correspondent.

And I saw how he was picking up the gentlemanly ways of my brother. When we stopped at a gas station for sodas, he quickly stepped forward. “I got this,” he said, confidently brandishing his pesos.

I was impressed. Where had this grown-up come from?

By evening, we had arrived at our hotel in Ixtapa, and suddenly the boy re-emerged. Bobby had only seen the Pacific once in his life, in California, where it was too cold for swimming. Could he please, please go in? I kept an eye on him frolicking in the water as I sat at the beachside bar, renewing my acquaintance with the pina colada.

The following morning was our date for parasailing. Fortunately, a drenching early morning storm passed and by noon, the sun was blazing. We drove to the main beach in Ixtapa and found a makeshift stand marked “Water Sports.”

Bobby’s parents had agreed that he could go parasailing, and all my friends had told me it was safe. But was it? I suddenly felt the unaccustomed weight of parental responsibility on my shoulders.

As Bobby’s body grew smaller and smaller in the sky, I worried. Was he flying too near the hotels?

The speedboat rounded a bend near a rocky outcropping and Bobby lost altitude. Oh, no – he’s going to crash, I panicked. But somehow, he stayed up in the sky until the Water Sports man blew his whistle and waved a red flag, signaling him to pull a special strap on the parachute.

And then, all of a sudden, Bobby was coming in for a landing. It all looked so controlled, so gentle, his glide to the beach. The Water Sports men ran over to catch him as he dropped onto the sand.

Bobby was smiling ear to ear. I had never seen him so happy.

“You’ve got to try it!” he yelped.

Until then, I had thought I wouldn’t parasail. Who would drive him back to Mexico City if I died? But now I couldn’t resist.

We both glowed as we left the beach to go back to our hotel. We had survived. And we had each experienced a little bit of magic up there, floating above the sparkling ocean and forest-trimmed beach.

“I think that was the high point of my life,” declared Bobby.

Parasailing wasn’t the high point of mine, I have to admit. I’m not sure what I’d classify as the pinnacle of my existence. But for simple pleasures and happy discoveries, it’s hard to beat a trip with your nephew.