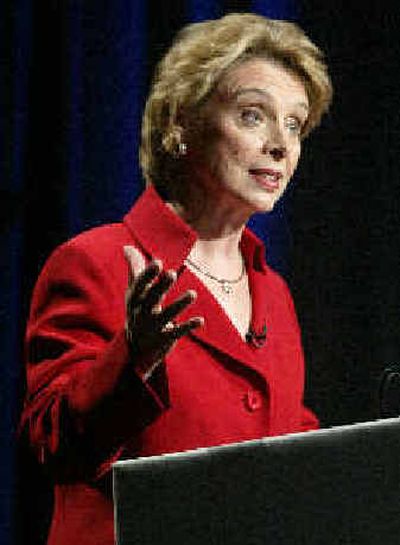

Gregoire aggressive in conflict

Editor’s note: This is the first of two profiles of Washington’s gubernatorial candidates. Coming Thursday: Republican Dino Rossi.

YAKIMA – During a pre-debate sound check in a Yakima theater last week, a TV technician asked the two major candidates for Washington governor to say something so he could test the microphones.

Republican Dino Rossi stepped up to the mic.”We’ll take an offering after the service,” he said, grinning. The crowd chuckled.

Then it was Democrat Christine Gregoire’s turn. She recited the 30-word first sentence of the Gettysburg address, pausing only to insert the words “and women” into Lincoln’s famous line about all men being created equal.

It was classic Gregoire – smart, focused and assertive. In earlier debates, Gregoire had been so intense that she came off as angry. Well-prepared, sure, but likable?

Some of the people who know Gregoire best, however, say there’s another side to the woman who would be Washington’s next governor, a side they first saw during her years as a law school student and young mother in Spokane.

It’s been more than 20 years since Gregoire, 57, left Eastern Washington for a succession of ever-bigger Olympia positions, including three terms as attorney general. But Spokane, as Gregoire likes to say on the campaign trail, is where she got her law degree, started her family and launched her legal career. She lived and worked here from 1974 to 1982.

Friends and co-workers from those years call it a formative period for Gregoire, with good times – and tragedy – that helped shape her into the person she remains today. She and her family remain close to many of the people she knew in Spokane. They spend part of nearly every summer at the small, rustic cabin that Mike and Christine Gregoire bought on Idaho’s Hayden Lake in 1979.

“Spokane is more like a small town,” especially for the city’s close-knit community of lawyers, said Cindy Whaley, a law school classmate. “I think it left its mark on her.”

“Here in Spokane, I think she saw the agrarian values that Spokane represents, people who’ve worked hard with their hands as much as their head,” said retired Superior Court Judge Jim Murphy, who hired Gregoire, still a student, to be his law clerk in the mid-1970s.

A Puget Sound native

Gregoire’s mother, Sybil Jacob, married at 17. Gregoire doesn’t remember her father. An infant Gregoire and her mother fled from him after domestic abuse, staying with Jacob’s sister in Enumclaw. The abuse is not something Gregoire will talk much about, other than to say that her mother got a restraining order that prevented her father from ever again having contact with either of them. Gregoire grew up in what was then rural Auburn, where she worked as a cook at the Rainbow Cafe, which still exists. She grew up on five acres, helping tend vegetables, care for calves and chickens, and canning food.

Gregoire eventually went to college at the University of Washington, graduating with a teaching certificate. When she couldn’t find work as a teacher, she got a job as a clerk-typist in a probation office. After a few years – and a promotion to welfare fraud investigator – she decided to go to law school. Sponsored by a longtime family friend in Moses Lake, she enrolled at Gonzaga University, one of only a handful of female law students at the time.

“If you looked to your left and right, you were surrounded by men,” said Whaley.

After a year, she married a former co-worker: fraud investigator Mike Gregoire, recently returned from service in Vietnam. Christine worked part time and took night classes when she could. She jetted around in a gold-colored MG convertible.

“Oh, man, she thought she was cool,” said Whaley.

In 1977, law degree in hand, Gregoire was hired as an assistant attorney general by Attorney General Slade Gorton. She worked with social workers in child-abuse cases, asking courts to remove children from dangerous homes and put them into foster homes or with relatives.

“Line work is tough. I used to compare it to a war zone – you’re in conflict situations all the time,” said Dee Wilson, a social worker in the office at the time. “When you’re removing children from people’s homes, you’re among angry people.”She was a formidable force in the courtroom, Wilson said.

“However else you would describe her, she is aggressive in a conflict,” he said.

Lots of friends and happy times

The MG was traded in for a family car when Christine Gregoire became pregnant with their first daughter, Courtney, born in 1979. The family lived in a ranch house on Spokane’s South Hill, near Manito golf course. That same year, they bought the cabin on Hayden Lake as an investment, something the young couple could sell when their children needed money for college.

Friends and co-workers describe those years as happy times. There were a lot of backyard barbecues with dogs and kids running around. Gregoire’s mother moved to Spokane, and the two women would take the baby to Riverfront Park.

“They didn’t have a lot of money then,” said Whaley. “I remember Mike and Chris one year working morning, noon and night making Courtney a toy box for her birthday.”

A daughter dies

In 1981, Gregoire was months into a second pregnancy when her doctors told her something was wrong. The baby wasn’t digesting the amniotic fluid properly. The fluid pressed on Gregoire’s lungs, making it hard to breathe. After weeks of worrying, Gregoire delivered the baby, named Laura. The baby died within hours.

“We knew there was trouble with her but we didn’t know how much trouble,” Gregoire said in an interview.

“She handled it with amazing grace,” said Gayle Ogden, a former Spokane assistant attorney general hired the same day as Gregoire. “They took time to grieve privately. Statistically, the loss of a child is very hard on a marriage, and I never saw that marriage skip a beat.”

“She just kind of looked to Courtney and said, ‘Life isn’t fair, but you have to deal with what you get,’ ” said Whaley.

She said she saw a similar resolve last year, when Gregoire learned she had early-stage breast cancer. Whaley’s mom had recently been diagnosed with cancer as well, and on a visit to Spokane, Gregoire stayed up late, talking to Whaley about the diagnosis.

“Your life is sailing along, and then – boom! Your first reaction is that you’re going to die, probably, but then you tackle it,” Whaley said. “She wasn’t going to waste a lot of time feeling sorry for herself.”

Gregoire had a mastectomy and says she has a clean bill of health from her doctor.

“It made her stronger, in her faith and her family,” said Whaley. Gregoire, like Rossi, is Catholic.

Leaving Spokane

In 1982, Attorney General Ken Eikenberry asked Gregoire to come to Olympia as the state’s first female deputy attorney general. After eight years in Spokane, Gregoire and her family moved to the capital. She later gave birth to another daughter, Michelle, now 19.

By 1988, Gregoire had been appointed head of the state Department of Ecology. After four years there, she ran for attorney general, a post she’s held for 12 years. She’s gained national fame as the lead negotiator for states on a $206 billion tobacco lawsuit settlement, and she’s been blasted over subordinates’ failure to file an appeal in a lawsuit, a screw-up that cost the state more than $20 million.

“Chris is the sort of person who respects her staff’s strengths and gives them the authority to handle their cases as adults and professionals,” said Murphy, the retired judge. “She’s not one who micromanages her office. And there’s bound to be a slip-up. Unfortunately, this was a case that involved a lot of money.”

The case was a gift to Republicans, who have made the mistake a centerpiece of their campaign against her. But it’s not the only thing. Rossi’s blasted Gregoire as an Olympia insider, a longtime part of the city’s clubby fraternity of high-ranking state agency bureaucrats.

Rossi’s campaign also keeps a list of expensive mistakes made by Gregoire’s office: Lawyers working for her failed to read the jury instructions in a wrongful-death case, resulting in a $22.4 million judgment. Her staff missed a key deadline in a state lawsuit against the city of North Bend. State lawyers failed to file charges for two years against a doctor who allegedly sexually assaulted patients, apparently because new charges kept rolling in and they wanted to build a stronger case.

Critics also point to Gregoire’s campaign-trail calls for more money for colleges, higher pay for teachers, more money to shrink class sizes and, within a few years, health insurance for all children. Gregoire has repeatedly been asked how she intends to pay for those things in the face of a likely state budget shortfall next year. She’s mostly dodged the question, except to say the public should have more say in the state’s budget priorities and that the state should reconsider some of the tax breaks it’s given out to various industries over the years.

“She wants to be a Rorschach test for people: Whatever you want to see, she’ll be,” says anti-tax crusader Tim Eyman. He thinks she’ll have no choice but to push for tax increases if elected.

“When you promise all things to all people,” he said, “somebody’s going to get shafted after the election.”

Finding a balance

Off duty, Gregoire balances out her life, friends say, with hobbies reminiscent of her childhood. She’s an avid gardener, growing carrots and pumpkins and other vegetables. Even this year, the family found time to can their own tomato sauce.The Hayden Lake cabin provides a similar respite, despite a long string of vacation-home crises – a broken water heater, broken door, dock repairs. It’s hardly a mansion – 800 square feet, and valued at just $36,000. (The land, with 50 feet of lake frontage, is worth almost three times that.) The family hauls in its own drinking water, and hangs its laundry. There is no phone.”It’s so special to the family,” Gregoire said of the cabin. “It’s a million miles away.”