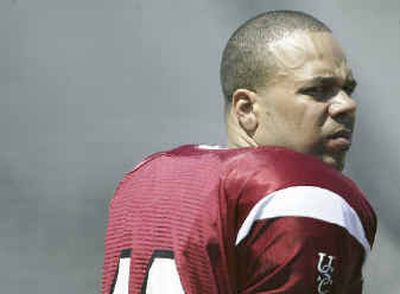

‘Pops’ Frisby soars to national attention

COLUMBIA, S.C. — The morning of South Carolina’s game against Troy, three executives from Paramount Pictures showed up at the house of Gamecocks receiver Tim Frisby.

Already, Frisby has appeared on CNN and ESPN2’s “Cold Pizza.” Two nights before, Frisby had been a guest on the “Late Show with David Letterman” in New York.

At least 100 representatives of newspapers, TV and radio stations across the country — from Sports Illustrated to the Syracuse University student newspaper to a Tucson, Ariz., sports talk show hosted by someone named “Pork Chop” — have called about interviewing Frisby.

Everyone, it seems, wants a piece of “Pops,” the only 39-year-old college football player in the country.

“It’s not something I sought out. I thought I could come in here and try out and, if I was capable of playing, play,” Frisby said. “Really my first three or four weeks in the program where I was unnoticed, that was great. I just wanted to play.”

But after ESPN’s “College GameDay” ran a feature this month on Frisby — a 20-year, Ranger-trained Army veteran and father of six who returned to school and tried out for a major college football program — the school began receiving as many as 30 media requests a day for Frisby.

The attention only intensified when Frisby, known as “Pops” by his teammates, played the final four snaps in a 17-7 win last Saturday against Troy. The national morning news programs and late-night talk shows jockeyed to land Frisby first.

“This was absolutely inevitable,” said Bob Thompson, a pop-culture expert in Syracuse’s Radio, TV and Film Department. “The very idea of a 39-year-old going back to college, that’s a story itself before you add the football element.”

Thompson believes Frisby’s story has the makings of a made-for-TV movie and perhaps a big-budget feature film.

“It would be even better if he were constantly throwing the winning touchdown,” he said, “but you don’t need that.”

DreamWorks, Sony, Warner Bros. and Paramount have inquired about Frisby.

Under NCAA rules, Frisby would lose his eligibility if he makes any formal agreements with a publishing or production firm.

Frisby directs all inquiries to assistant sports information director Gavin Lang, who has spent the past three weeks serving as Frisby’s handler/publicist. Lang takes everyone’s number and tells them Frisby will get back to them after the season is over.

But that didn’t stop Paramount executives from showing up — unannounced — at Frisby’s northeast Columbia home. Frisby had run out to the store, and his wife, Anna, was at work. But the couple’s older children asked the men to wait outside until their father returned.

No financial terms were discussed. At this point, the motion-picture companies are just trying to make contact with Frisby, Thompson said.

With U.S. forces in Iraq, Thompson said Frisby’s military background also would play well in Peoria. Although he served during the 1991 Gulf War and the Kosovo conflict, Frisby points out that he was far from the front lines.

Frisby, a human resources specialist whose highest rank was sergeant first class, was in Stuttgart, Germany, for the Gulf War, protecting an Army base from a possible terrorist strike. He also helped transport equipment to U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia. Frisby was stationed in Italy in 1999, providing ground communications for U.S. troops in Kosovo.

“I wasn’t on the ground like these guys, taking casualties and stuff like that,” Frisby said. “You’re talking about heroes. I don’t even mention myself in the same breath. Those guys are actually down doing the dirty work.”

But there is a part of Frisby that prefers doing the dirty work and taking on challenges that would appear extreme — or even foolish — to outsiders. Eight years after he joined the Army right out of high school, Frisby volunteered for Airborne training and later received a waiver to go through Ranger school, which included parachute jumps into the Great Smoky Mountains.

All along, Frisby — a two-sport high school athlete in Allentown, Pa. — kept himself in shape playing Army basketball and football. While based at the Pentagon in the mid-1990s, Frisby and his Army buddies used to play pickup basketball at Georgetown with a group of Hoyas that included Allen Iverson.

Frisby declared himself eligible for the NBA draft in 1996. Frisby insists it was not a publicity stunt, but rather an educational tool.

“I didn’t do it as a lark,” he said. “I just did it as kind of a feeler to see if people out there were watching, how they went through it.”

Caroline Frisby, a retired physician’s assistant, raised five boys on her own after her husband died of prostate cancer when Tim Frisby was 2.

The Frisby boys advanced to varied and successful careers in mechanical engineering, insurance, construction and business. But one never stopped dreaming about being a college athlete.

Despite averaging only five points as a high school senior in 1983, Frisby received a scholarship offer to Tennessee State, whose coach had connections in Allentown. But so-so grades convinced Frisby he wasn’t ready for college, so he enlisted instead.

A transfer in 2002 brought Frisby and his family back to Columbia, where he was stationed at Fort Jackson from 1984-88.

He started taking classes at South Carolina and called the football office about trying out, but was told only full-time students were eligible.

When he began taking a full load in broadcast journalism this past spring, Frisby called back. The rest is history still in the making.

“I didn’t want to be one of these guys talking about it: ‘Hey, this guy’s no good. I could be out there playing,’ ” Frisby said. “Until you’re out there doing it, then you’ll see how good these guys are or how good you are. You have to measure yourself against it.”

Frisby, 6-foot-1 and 188 pounds, is not expected to travel with the Gamecocks to Alabama this weekend. For now, his role is with the scout-team offense.

Coach Lou Holtz put Frisby in for the final 2 minutes against Troy as a reward for his work in the off-season program and his unselfish attitude. Receiver Kris Clark said other players are not resentful of the attention Frisby is receiving.

“We all just laugh about it,” Clark said. “We tell him, ‘When you make the big time, give us a shout-out. Remember where you came from.’ ”

With six children between the ages of 6 months and 16 at home, Frisby realizes what a potential six-figure option could mean to his family.

But he also knows it would mean the end of his football dream.

“At this point, I think we’re just blessed that he’s able to play football, which is something he always wanted to do,” Anna Frisby said.