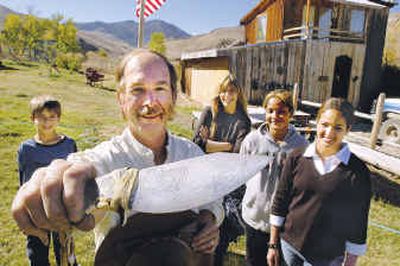

Idaho knife maker says old ways give him edge

SALMON, Idaho – Joseph Bigley fashioned his first set of handmade knives when he was just a teen, using mostly his own ingenuity.

Some four decades later, the 53-year-old Salmon man can claim a hand in the shaping of hundreds of knives and almost as many lives.

For Bigley, who retired from the military in 1996, crafting knives is a personal experience, one in which the maker and the knife forge a bond as strong as steel.

“Knives tell you what they want to be,” Bigley said. “You may start out forging a certain shape and it will come out being something entirely different. What it becomes is really what this thing is meant to be.”

His philosophy about knife making ties closely to his beliefs about a society he thinks has become too reliant on what he calls “modern inconveniences.” So it is not surprising the strategies Bigley employs to produce blades and make handles from antlers are simple and accessible.

“I’ve had people come out here and say, ‘You can’t make knives in that,’ ” Bigley said of the shed he works in, the open flame he uses as a forge and the kitchen oven that doubles as a kiln. “I say, ‘Oh, I didn’t realize that; I’ve only made about 500 of them.’ “

Bigley’s instinct to make his own tools took root during a hunting trip with his father when he was 7.

“My dad had shot a deer and I went to get the knife to gut it,” he said. “The knife was missing, so I thought I’d have to backtrack to the vehicle to get it. Instead, my dad grabs a football-sized rock, smacks it two times against a boulder and comes up with a disc-shaped flake. He said, ‘Here’s your knife, son.’ “

Today, Bigley’s income is dependent on such techniques, known as primitive skills. He and his wife, Denyce, spend part of the year teaching things such as hide tanning, basket weaving and “food procurement” to people with a penchant for self-reliance.

Bigley charges $35 for his workshops on knife making. He charges $20 an hour for custom work, with most knives taking about five hours to fashion.

Bigley backs up his work with a lifetime guarantee, telling customers: “It will last for life, yours or mine, whichever comes first. And if you use the knife for knife work – not trying to saw a cinderblock, for example – then it will last forever.” Although he has worked with several metals, he prefers to work with a material with a high carbon content. The higher the carbon content, said Bigley, the more likely a knife is to hold its edge. He says there’s no such thing as a perfect blade, but Bigley says it should nevertheless meet certain standards.

“You have to be able to sharpen the thing, and it’s got to hold its edge for more than a couple slices,” he said. “It’s got to be strong but flexible enough so that when you put pressure on it, it doesn’t snap.” Whether working with a power hammer or a blacksmith’s mallet, Bigley likes to think he is reproducing the spirit that infused knife makers since time immemorial.

“Rather than going toward something, I’m going back to something,” he said.