Grecian formula

The face of this fall is Greek – Macedonian, to be exact.

He’s young, handsome, maybe even gay. And 2,300 years old.

Blond or brunet, gay or straight, Homeric hero or paranoid genocidal conqueror, Alexander the Great has been turning up everywhere this month – in bookstores, in games, on video and on cable television.

And on Wednesday, capping it all, Oliver Stone’s film “Alexander” comes to a cineplex near you.

Alexander was a historic colossus “who aimed for the heights and reached them, conquering much of the world and spreading the reach of Western civilization,” says Robin Lane Fox, historic consultant on Stone’s film.

“He was an ambitious leader who met his end in the deserts of Persia,” says Paul Cartledge, author of the new biography “Alexander the Great: A New Life” (Overlook Press, 368 pages, $28.95). “People can’t help but see parallels to modern times.”

And let’s face it, says Jim Lindsay, writer-producer-director of The History Channel’s recent “Alexander the Great” documentary: “How many people in history go down with just ‘The Great’ as their last name?”

A king at 20, emperor at 25, with his dominions stretching from Sicily to India, Afghanistan to Egypt, he led an army that was often outnumbered but never defeated.

“In 32 brief years, he set the stage for the modern world, creating the connections that led to the Roman Empire and the later spread of Christianity,” says Cartledge.

“A figure truly unequaled in history,” declares Fox, who has spent much of his career writing about Alexander. His definitive 1973 biography, “Alexander the Great,” is now back in bookstores (Penguin, 576 pages, $15.95 paper).

Alexander was raised to be “great.” He was the product of extraordinary circumstances, says William Murray, professor of history at Tampa’s University of South Florida.

“His father was King Philip of Macedonia, this great warrior who taught him how to wage war,” Murray says. “His mother was Olympias, who gave him ambition and this sense that he was chosen by the gods to rule.”

And the future emperor had one of the most famous teachers in history.

“You can’t overstate the fact that Aristotle was Alexander’s teacher,” says Cartledge.

Philip brought the great thinker in to teach his boy, and the result “was an adult who never ceased being curious about the world, about what was just over that next hill,” says Murray.

Lindsay sees Alexander “as the classic product of a liberal arts education, maybe the first liberal arts education. And what did he learn? How to solve problems, to think outside of the box, to improvise.”

That served Alexander in good stead in his invasion of the Persian Empire, the siege of Tyre and in combat against creatures he and his army had never seen – elephants at the Battle of the River Hydaspes.

But more important, says Fox, Alexander’s curiosity pushed him to spread Hellenism and to bring knowledge of the wider, unknown world back to the Greek city-states.

Alexander wanted “to see the edge of the world,” Fox says. He sent back specimens of the animal and plant life he encountered during his thousands of miles of marches. What’s more, he seemed to respect and learn from the peoples he conquered, basically leaving existing government and religion and administration intact after crushing the Persians.

“I will believe, to the end of my days, that there is no way that somebody tutored by Aristotle, with a sharp brain and a clear, politically astute mind … with the intelligence to win these vast battles, did not have a vision,” Fox says.

“Did he do what he did because he was like some war-drunk veteran who loved to be drenched in blood? I don’t believe it.”

That view of Alexander – as “an ancient Greek version of Stalin,” as Cartledge puts it, murdering those in his ranks whom he suspected of conspiring against him, killing as many as 750,000 enemy soldiers and civilians – has been a major bone of contention among modern historians.

Fox has spent much of his career fighting that perception, “this grinding down of Alexander” by his fellow historians.

“You can say that his whole life was this regrettable, bloodstained event,” Fox says. “Or you can see him as I think he saw himself, as the reincarnation of Achilles, the great warrior avenging the Greeks upon the Persians. As a historian, you have to take both views.”

Cartledge, who leans more toward the megalomaniac interpretation, agrees.

“You can think, ‘He must have had this insatiable blood lust,’ ” Cartledge says. “On the other hand, can you accept that conquest is what he’s about? You can’t reduce someone as complex as Alexander to a simple character in black and white.”

“Complex” doesn’t begin to cover Alexander. There’s the matter of his sexuality. Alexander’s actions, and oblique historic references, tend to suggest that his attachment to his lifelong friend and companion Hephaestion was both fraternal and sexual.

Then there was the Persian eunuch to whom Alexander took a shine after crushing the Persian Empire.

“He was not abnormal at all in his bisexuality,” says Fox. “He had concubines, wives. He produced children. What he is not is a one-way gay man, standing for gay triumphs as a counterculture against the heterosexual world.”

Cartledge seconds that.

“If you’re gay, you might want to claim a really powerful figure from history as one of your own,” he says. “But the fact is that he slept with males as well as females. It was treated as a phase young men went through.”

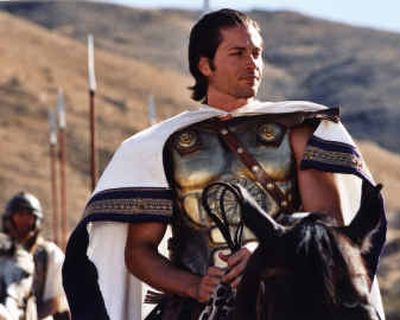

Today’s historians are eagerly awaiting the Stone film. Colin Farrell plays the blond Alexander. Jared Leto (“My So-Called Life”) is Hephaestion. Christopher Plummer plays Aristotle, Angelina Jolie is Olympias and Val Kilmer is King Philip. Anthony Hopkins plays the aged Ptolemy, Alexander’s friend and trusted general who wrote the first “definitive” history of the conqueror.

Lindsay looks forward to seeing Stone’s treatment: Did Alexander have his father killed? Did he come to believe himself a living god? What caused his death?

Murray, who has tried to get his University of South Florida students to make and march with “sarissas” – the 18-foot-long pikes that Alexander’s infantry carried – is eager to see “just what 40,000 Greeks and 150,000 Persians look like.”

Cartledge, who sees many connections between Alexander’s fate in the Middle East and the fate of American and British occupiers of Iraq and Afghanistan, is curious about what the notoriously political Stone will have to say about that.

Alexander “tried to emulate some of the practices of the peoples he conquered, to make himself acceptable to those peoples,” Cartledge says – something, he adds, that today’s political leaders could learn from.

Consultant Fox says there isn’t much of that in the movie. What there is, he says, is action.

And before he would agree to consult on the $150 million epic, the British historian presented the American filmmaker with one condition.

“Any battle scene, with cavalry in it, I’m in it,” Fox told Stone. What historian worth his or her degrees, he asks, wouldn’t want to know what it was like to be on horseback with no stirrups (they hadn’t been invented yet) and charge with Alexander’s cavalry?

“I was there, at the Battle of Gaugamela, 400 cavalrymen coming after me, and they couldn’t catch me,” chuckles Fox, a veteran horseman still giddy at how carried away he was on that day. “I had to be disarmed before I hurt somebody.”