Rathdrum Prairie is disappearing fast

The Idaho Supreme Court is expected to soon rule whether hastily passed legislation shields farmers who grow Kentucky bluegrass in North Idaho from lawsuits when they burn off the stubble in their fields.

But whether farmers win or lose on the constitutionality of House Bill 391, the ruling could be meaningless because the Rathdrum Prairie, center of the field-burning debate, is almost gone.

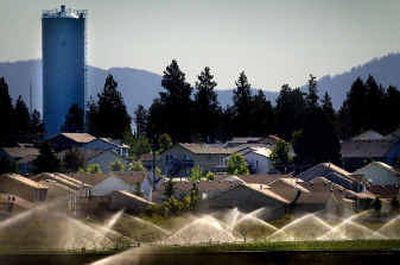

A recent inventory of the 100 square miles of prairie reveals that only 10,000 acres – about 15 square miles – can still be considered open space. And land on the prairie, the coarse, porous cap over an aquifer that supplies drinking water to nearly half a million people in the Spokane and Coeur d’Alene area, has been vanishing under pavement and rooftops at an average rate of 1,000 acres a year for the last decade.

Even as grass-seed growers and clean-air advocates battle in lawsuits and legislatures, a wide-ranging coalition has been quietly working to try and preserve what open space is left.

“This will be our last chance,” said Kootenai County Planning Director Rand Wichman, a key player in the group that is trying to find a path through the maze of land-use issues on the prairie.

The Rathdrum Prairie Open Space Project includes county and city politicians, land-bankers, farmers, water quality specialists, board members of local water and sewer districts and the sort of techno-wonks who are comfortable speaking to the fine points of aquifer recharge, the minutiae of tax laws and pollution limits.

The Open Space Project has been working largely under the radar but has scheduled two meetings at the Kootenai County Administration Building in Coeur d’Alene this week.

Tuesday evening at 6, prairie landowners will be invited to explore conservation easement options to resist the market forces that lead to the subdivision and development of open land. On Friday at 9 a.m., County Commissioner Dick Panabaker has scheduled a town hall meeting on the subject.”There is a sense of urgency,” Wichman said. “We have to make something happen in the next three or four years, or we will have missed our opportunity. We are the last generation that gets to make this choice.”

Keeping the farm

The Rathdrum Prairie Open Space Project is not concerned specifically with the debate over turf grasses and field burning. But open space backers do see the preservation of farming as a key element in their proposals.

Largely, the drive to preserve open space is seen more in terms of controlling the explosion of suburban homes across the prairie and protecting the quality of the drinking water in the Rathdrum Prairie-Spokane Valley Aquifer.

And, in a roundabout way, open space is seen as critical for meeting clean water laws for the Spokane River. Cities around the prairie face an impending dilemma as a booming populace pushes the limits of municipal sewer systems. It’s not that the pipes are bursting or tanks are sloshing over. There are strict federal and state limits on how much treated sewage can be discharged into the Spokane River. There are two choices, Wichman said. One is to raise tens of millions of dollars to upgrade sewage plants so cleaner effluent is sent to the river. The other is to separate treated effluent – more akin to gray water than sewage – and use it as irrigation water on farmland.

This approach, called land application, could help preserve open space, as cities or sewer districts buy land for such uses and lease the farming rights, Wichman and others said. The city of Hayden’s sewer district has been doing this for five years. Post Falls is beginning the process this summer.

The buy and lease-back option is one of many to be presented to farmers at Tuesday’s meeting. Other options include conservation easements in which a landowner relinquishes development rights in return for property tax and estate tax breaks.

Tired of debate

How the issue of turf-grass farming fits into this is anyone’s guess. The question of field smoke is a wild card that still needs to be addressed, but a number of people see the Open Space Project as a chance to find a solution that can satisfy all sides.

Peter Erbland, a Coeur d’Alene attorney representing grass growers in a number of lawsuits, said Kentucky bluegrass may give way to alternate crops such as mint or groves of fast-growing poplar trees for pulp and paper markets.

But, he said, “The farmers certainly would have an interest in discussing any of that, I believe.

“I think people are tired of debating the pros and cons of field burning. For someone to suggest there may be a creative solution to this debate that satisfies many of the interests is refreshing,” Erbland said.

And that’s because everybody knows what could be lost, he said.

“I was just up on Canfield Mountain,” he said. “You look down and you can see the entire prairie. I’ve been going up there for years, and if you could have time-lapse photography you would see large green spaces – just beautiful – but the large, beautiful green spaces are disappearing. I don’t know how long it will take until they are gone.”

Essentially, they are gone now, Wichman and others say, unless people in various interest groups work together to save as many of the remaining 10,000 acres as they can.