The politics of paranoia

It’s been a big month for paranoia. This week’s “The Manchurian Candidate” and “The Village” follow “I, Robot,” and “The Bourne Supremacy” into theaters. And, once again, just because our hero is paranoid doesn’t mean everybody isn’t out to get him.

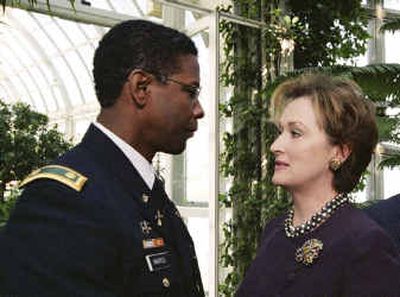

He’s Denzel Washington, a former soldier on the trail of a soulless corporation called Manchurian Global. Manchurian is somehow involved with a U.S. senator (Meryl Streep) and her son (Liev Schreiber), a candidate for U.S. vice president.

“Manchurian” is a remake of the prescient 1962 classic; the story’s similar, but the tone is grimmer, less satiric, and the ending has been altered. “Manchurian” is also a startlingly effective return to form for director Jonathan Demme, making his first good movie since “The Silence of the Lambs.”

Washington, convinced somebody has messed with his brain, spends much of the film gazing directly into the camera, as if aware he’s being watched. It’s a clever in-joke. Demme is revealing that he knows the reason paranoia works so well in the movies is because the paranoid character really is being watched. By us. And, if we’re not actively seeking to harm him, neither are we lifting a finger to help.

The reason this “Manchurian” works is twofold. There’s fine acting all around. Only Streep, whose role has been given a witty, glass ceiling-based motivation, isn’t as good as the original (she’s capable, but her malevolent baby talk is no match for the snarly elegance of Angela Lansbury). And there’s also a creepy sense that the movie isn’t far from the truth. Evil corporations do have too much power. They do have elected officials in their pockets. And politics is a vicious, dirty game.

That simple idea powers the movie effectively, except in the draggy, lecture-y middle. “Manchurian” even makes ambiguity dramatic and disturbing – the hero isn’t entirely heroic, and the villain isn’t entirely villainous. Their plights are so disturbing, their paranoia is so real, because they both fear someone has tampered with, literally, the last place where we can all remain free: our brains.