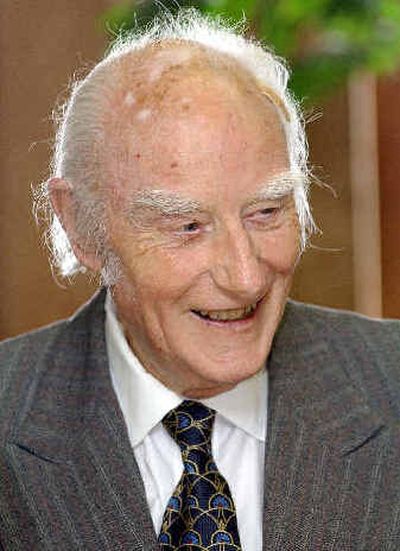

Francis Crick, co-discoverer of DNA, dies

Francis Harry Compton Crick, co-discoverer with James Watson of the double-helix structure of DNA – what came to be understood as the genetic blueprint for life – died Wednesday after a long battle with colon cancer. He was 88.

Crick, who shared the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1962 with Watson and another scientist, Maurice Wilkins, persevered in recent years in the face of advancing age and sickness, showing up several days a week at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego. He remained active in pursuit of his scientific interests, which in recent decades concerned the neurobiology of consciousness.

But the discovery that guaranteed fame – and led to developments ranging from crime suspect identification to gene therapy and bioengineered tomatoes – came in 1953 at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, when Crick, then 36, was in pursuit of the mysterious molecular structure of DNA. At the time, DNA’s role as a key to understanding life was unknown.

It was there that Crick met Watson, a brash scientist who already had his post-doctoral degree while Crick was still working on his. Of their discovery, Watson, now chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories, said, “We were jolly lucky.”

“I will always remember Francis for his extraordinarily focused intelligence and for the many ways he showed me kindness and developed my self-confidence,” Watson said Thursday. “For two years I was almost a family member, the much younger brother prone to intellectually stray …

“Until his death, Francis was the person with whom I could most easily talk about ideas. He will be sorely missed.”

Watson and Crick’s relationship was challenged when Watson was writing “The Double Helix,” an account of their discovery that was published in 1968. Crick got wind of a comment Watson made in the book – “I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood” – and tried to stop its publication. The resulting chill lasted several years.

According to Jan Witkowski, executive director of the Banbury Center at Cold Spring Harbor, Crick and Watson initially shared a laboratory and a goal.

“They hardly did an experiment together,” he said. “They did a lot of thinking about what the structure might actually look like.”

In short time, they realized the shape was helical and consisted of two chains. But the question remained: How to fit them together?

They figured it out and published their findings in the April 2, 1953, issue of the journal Nature.

When the Nobel was awarded nine years later, it also cited Maurice Wilkins, for the role of his X-ray photography of DNA. Though similar work by Rosalind Franklin was important to the discovery, she was not honored, having died in 1958. The award is not presented posthumously.

Crick “was larger than life, in every sense,” said Dr. Gerald Edelman, a Nobel laureate and professor at the Scripps Research Institute and director of The Neurosciences Institute. “He was personally and intellectually energetic and curious, and he was engaged right to the end – a mark of a great scientist.

“When he was in a room, you certainly did not fall asleep.”

Eric Kandel, a Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist at Columbia University, Thursday hailed Crick as “one of the giants of biology in the last 50 years.”

Crick and Watson’s discovery, Kandel said, “opened up the molecular biological story of how information is transmitted within cells.”

He also praised Crick’s pioneering work in deducing how genetic information is stored within DNA’s four-letter code, transferred to an intermediary known as messenger RNA, and then translated into strings of amino acids that form proteins – a fundamental process often called biology’s central dogma.

Crick must have felt the same way about his discovery. This four-letter code spelled out his license plate – ATCG, the initials of adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine.

Crick, with his white bushy eyebrows raised high by his energy, enthusiasm and wit, had also raised many an eyebrow with his far-fetched ideas. In the early 1970s, he was chasing an idea that Earth life originated from micro-organisms sent to the planet on an unmanned spaceship. But that chapter of his life was short-lived and Crick entered neurobiology in 1979, taking up the study of consciousness.

Born in Northampton, England, on June 8, 1916, Crick came from a middle-class family who readily accepted his love of science, according to his autobiography, “What Mad Pursuit.” He confided his childhood fears to his mother that by the time he grew up “everything would be discovered.”

He trained in physics, and in World War II designed circuits for ocean mines that could differentiate the magnetic fields and sounds of a mine sweeper from those of other ships. When the war was over, he turned to biology.

He is survived by his wife, Odile Speed, an artist; three children and four grandchildren. Crick and his first wife, Ruth Doreen Dodd, divorced in 1947.