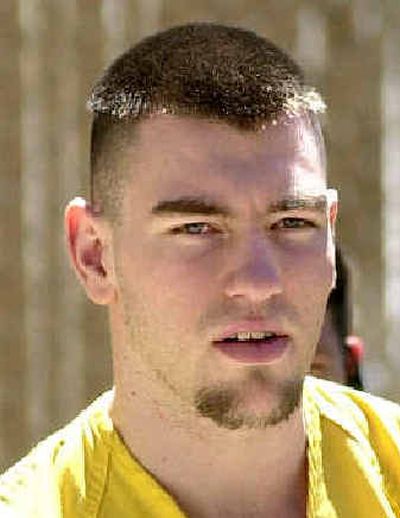

Early release denied for Cody Merritt

Cody Merritt was only 16, but he still got the tattoo; the same one worn by his dad and a shadowy group of his dad’s pals. Merritt was so proud of the black rose tattooed on his upper arm that he had it touched up several times, even as the headless body of Carissa Benway lay in the forest east of Coeur d’Alene waiting and waiting and waiting to be discovered.

The “brotherhood of the black rose” is a brotherhood of killers, police say, and at age 16 Cody Merritt earned his black rose tattoo by helping his dad, David “Coon” Merritt, lure the 14-year-old Benway to a campground in the Coeur d’Alene Mountains where the girl was raped, sodomized and beheaded. The elder Merritt was convicted of murder and is serving a life sentence without possibility of parole.

The creepy power of the black rose wasn’t contained by the sleeves of Cody Merritt’s Idaho Department of Correction prison garb last week when he was escorted into a windowless room at the Idaho State Correctional Institute near Boise for a parole hearing. The image of the tattoo, and its meaning, burned in the minds of the parole board, minutes of the hearing and interviews show.

Cody Merritt knew, he has told detectives and prosecutors, that Carissa Benway was going to die horribly when he and his father took the runaway girl on a camping trip just before the Fourth of July in 2000. He knew he would earn a black rose if he helped out. His desire for the tattoo was stronger than any compulsion to help Carissa Benway stay alive.

Why, parole board commissioner Mike Matthews asked during the July 22 hearing, didn’t Cody Merritt report the crime instead of getting his black rose at a Coeur d’Alene tattoo shop after the murder?

“Subject says he was afraid of repercussions from his father and his uncles,” the minutes of the hearing say.

Reading the minutes, it is clear the commissioners were troubled that Merritt still didn’t grasp the full gravity of his choices four years ago. The murder of Carissa Benway was so gruesome that all five commissioners on the parole board gathered for the hearing. Typically, only three are on hand.

“This was a very, very serious crime,” said Olivia Craven, executive director of the Idaho Commission for Probation and Parole.

The commissioners denied Merritt early release, noting he is only serving five years – earning a light sentence in exchange for providing information that helped convict his dad. The commissioners were also troubled that Merritt is doing little to seek out counseling or other help in prison.

Sgt. Brad Maskell, the Kootenai County Sheriff’s Department detective who, starting with a jawbone found by hunters, helped solve Benway’s murder, is worried Merritt will leave prison in 2007 as a messed-up and violent 22-year-old. “I fear for what kind of felon he will be when he’s released. I would like to think the state is making available to him some kind of mental counseling,” Maskell said.

“We are all worried about that,” Craven said. “He needs a lot of help before he gets out. What’s frightening is the short sentence he got.”

Maskell called the five-year sentence as accessory to murder “the bare minimum for being part of a crime that heinous.”

Bill Rodenbach, a hearing officer who conducts preliminary interviews with inmates, recommended the parole board deny Merritt’s plea for early release, citing, among other reasons, “his lack of further programs that may allow him to gain further insight into his past behaviors.”

Prison staffer Jon Lang, who works with the Violent Youth Program, said Merritt would be welcome to join the program but has not.

Benway’s mother, Bonnie Heilander, countered a number of statements Merritt made to the parole board by reading statements Merritt made in interviews with Maskell during the investigation.

“He admitted he always wanted the tattoo,” the minutes show Heilander as saying. “He said he wanted the rose because it looked good.”

In a series of interviews with Maskell during 2001, Cody Merritt told the detective he stood guard outside a tent as his father raped and sodomized Benway after using zip-ties to bind her to a pole inside. The boy said he had “consensual sex” with Benway later that night as his father lay sleeping.

He told Maskell he did not try to escape with Benway or alert nearby campers. He told Maskell he knew his father intended to kill the girl and was with Benway in a forested draw when it happened.

He got the tattoo a few days later.

At his parole hearing last week, the last line in the minutes shows that Cody Merritt told the parole board “he plans to get the tattoo removed.”

Maskell said he heard the same thing a few years ago.

“My biggest fear is he is going to come out of prison without any help after participating in a gruesome and nasty criminal act; and that he could act out aggressively. I fear he doesn’t grasp the weight of the crime.”