An Olympic dream spoiled

Orphans.

That’s what the 1980 U.S. Olympians consider themselves. Their dreams torn apart when their country boycotted the Moscow Games, they occupy a curious place in history: Qualifying for a team that went nowhere, they both won and lost simultaneously.

“If we go out to Colorado Springs (to the U.S. Olympic Committee headquarters), they have a kiosk, ‘Find your favorite Olympian,’ ” said swimmer Glenn Mills, 42, who lives in Stevensville, Md. “I punch in my name, and all it says is: ‘Did not compete; photo not available.’ It’s like, ‘Oh, my gosh, 17 years of work, and this is all that’s left.’ “

As this year’s Summer Olympics in Athens approaches, the past few months have been colored by terrorist concerns, which raised the possibility that the U.S. might not send a team and caused a few athletes to back out.

For the 1980 Olympians, it’s a flashback to the surreal spring of the boycott announcement.

Archer Darrell Pace, 47, of Hamilton, Ohio — who won a gold medal in 1976 and again in 1984 — and canoeist Roland Muhlen, 61, of Cincinnati took solace from previous Olympic trips. Mike Sylvester, 52, of Loveland, Ohio, who claimed dual nationality with Italy, won silver with the Italian basketball team.

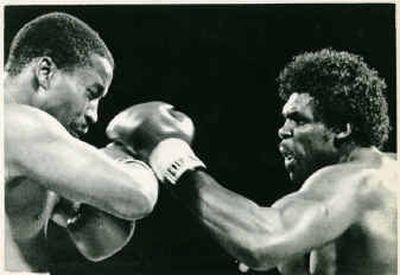

Boxer Tony Tubbs, 46, turned pro when the boycott was announced, skipping the Trials. Swimmer Kimberly Carlisle, 43, of Menlo Park, Calif., couldn’t watch the Olympics for 12 years, and diver Barb McGrath, 46, who lives in suburban Cincinnati, still admits an ache each time the Games return.

“I find a surprising number of people that don’t realize America didn’t go in 1980,” Sylvester said. “Only the ones that got shafted are the ones who are going to remember it forever.”

A generation ago, the Olympic movement was moving backward.

The 1972 Summer Games in Munich were shattered by the slaying of 11 Israeli athletes by Arab terrorists. The Montreal Games in 1976 endured a boycott of 32 nations and East German drug accusations. The Soviet Union and 13 Communist allies reciprocated for the 1980 boycott by shunning the 1984 Games in Los Angeles.

Yet 1980 was the low point. It remains the largest boycott in Olympic history: 61 countries, including West Germany, Japan, China and Canada. The greatest blow was to the Olympic ideal — the belief that nations could set aside differences and commune through the universal language of sport.

“They should hold the Olympics in neutral territory on an island somewhere and put a secure fence around it,” Pace said. “Let the world do their wars, their bickering — let us go do what we need to do.”

Even in hindsight, athletes remember the boycott as inevitable. The Carter administration had already initiated a partial embargo on grain sales to the Soviets, and the public seemed to back an OIympic boycott. It was awkward for the athletes.

“If you said you wanted to boycott, people turned around and said, ‘You trained for four years - you don’t want to go?’ ” Muhlen recalled. “If you said you didn’t want to boycott, it’s, ‘OK, then you’re un-American.’ “

Tubbs, then considered the heavyweight co-favorite with defending gold medalist Teofilo Stevenson of Cuba, would win a share of the splintered world heavyweight championship in 1985, but has suffered from drug addiction and is in prison a third time.

“I felt ripped off,” Tubbs said from prison in Chillicothe, Ohio. “You realize one thing: The Olympics is just like becoming the heavyweight champion of the world. It’s almost bigger than the title.”

Swimmer Bill Barrett, 44, who lives in Phoenix, missed the most. He qualified second in the 100-meter breaststroke, in a time that would prove better than the eventual gold-medal winner. Barrett also held the world record in the 200-meter individual medley and won that event at the Trials. In 1984, he narrowly missed making the Olympic team.

“It was a very tough but a very good lesson to learn in life — that you can do everything right but still not be able to reach your ambition or goal,” he said.

One day in 1989, Carlisle was in a New York taxi. Her driver told her he had been a banker in Afghanistan but had fled his war-torn land. Just then, they heard on a radio news bulletin that the Russians had finally pulled out of Afghanistan. Carlisle wept.

“It was profound,” she said. “Here was this man who was very accomplished, who had to leave his home country and drive a cab, and I was whining about not getting to go to the Olympics. It brought everything home.”