Correia hopes to be minority role model

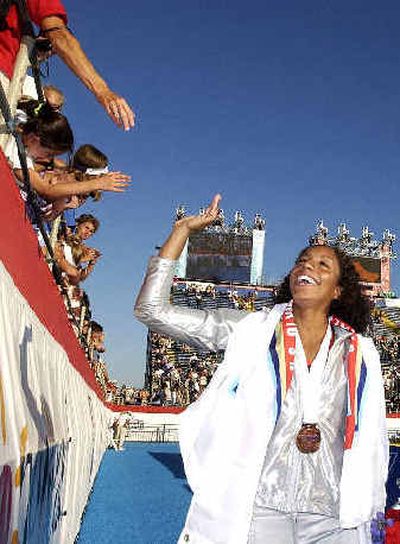

LONG BEACH, Calif. — Maritza Correia didn’t have to win to make history.

With a fourth-place finish in the 100-meter freestyle, she became the first black woman to qualify for the U.S. Olympic swim team.

“I’m amazed, I’m shocked, I’m happy,” said Correia, who now has a chance to be part of the 400 free relay in Athens. “It’s a great honor. I hope I’m one of many.”

Correia’s finish Monday night in the U.S. swim trials allowed her to join Anthony Ervin as the only blacks to make a U.S. Olympic swim team. Ervin tied teammate Gary Hall Jr. for gold in the 50-meter freestyle at the 2000 Sydney Games, then retired earlier this year.

Ervin, who has a white mother and a father who is 75 percent black, downplayed his race.

“I don’t look black,” he said

But Correia wants to be a role model for minorities, hoping her success will open up the mostly white sport.

“I don’t think it’s the main focus, but if I can use it to my advantage, I will,” she said. “It’s really hard for minorities to get the facilities. It’s a very expensive sport. My goal is to get more pools built.”

Her vision is shared by Olympic teammate Lenny Krayzelburg, a triple gold medalist at Sydney. He has his own foundation that hopes to bring the sport to more inner-city children.

“Let’s face it — swimming is a middle- and upper-class sport,” he said. “You have to practice five hours a day. When you’re 12 years old, you don’t have a car. You’ve got to have someone who can drive you to practice, pick you up, maybe wait around all day.

“Your family has to have some financial flexibility so you can do it.”

Correia competed in three events at the 2000 trials, but didn’t come close to making the team. Since then, she’s steadily progressed, winning relay medals at the world championships last year and in 2001, and five NCAA titles at Georgia.

The 22-year-old swimmer nicknamed Ritz could have qualified for the Olympic team in her native Puerto Rico, but she preferred the more difficult U.S. trials.

Her parents are from Guyana.

“This is definitely my biggest accomplishment yet,” she said.

Correia started swimming as a 7-year-old when a doctor suggested the sport could help with her scoliosis, a curvature of the spine.

“I didn’t want to wear a brace or get surgery or anything like that,” she said. “My back was about 15 degrees off center and she said that the more I swam and corrected my posture as I walked around, things would get better.”

Besides, Correia loved tagging along with her mother to the beach.

“My parents let me do my own thing and I liked it,” she said.

Correia wasn’t an instant success in the pool. She competed in her first senior national meet in 1997 and finished seventh in the 800 freestyle. In 1998, she was 17th in the 100 free, then moved up to a seventh-place finish in that race the next year.

“I’ve always had those close calls where I just missed,” she said. “My career has been very slow. It was a bumpy road, but I stuck with it.”

Correia’s results picked up once she started swimming at Georgia. She earned her first NCAA title as a freshman in the 200 free.

Georgia coach Jack Bauerle recruited Correia for her talent, not her race.

“I just wanted to have her on my team,” he said. “But if it helps other African-American swimmers come into the fold, all the better.

“If someone can have a lot of success in our sport, that’s who others will identify with. And she’s a good person to identify with no matter what her race.”

Until the trials, Correia’s greatest successes had been in relays.

“She single-handedly lifted us out of the dust at the 2001 NCAA championships,” Bauerle said. “She went into the water over a length behind in the 400 free relay and came back to win. She’s the best relay swimmer I’ve ever seen.”

Correia’s confidence didn’t always translate to her individual races, where the pressure to swim for herself was greater than when she was helping her teammates.

But Bauerle saw a transformation in Correia at the trials.

“All of a sudden, she’s focusing in on her time,” he said. “She’s always been such a relay swimmer. She’s getting more confidence in herself.”