Enron debacle a criminal mess

HOUSTON — The criminal cases coming out of the investigation of Enron’s collapse, which now include one against former CEO Kenneth Lay, radiate like the spokes on a wheel.

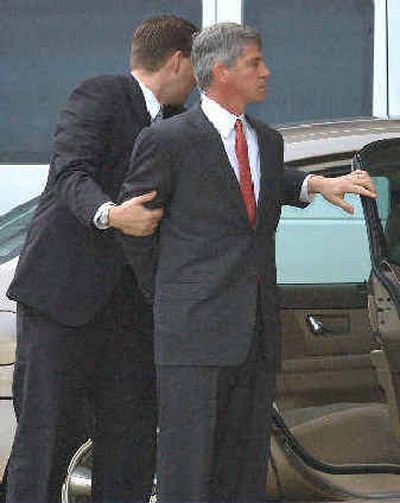

Lay, the 62-year-old Enron founder and former chairman, on Wednesday became the 30th individual indicted or charged as part of the probe launched just weeks after the company’s collapse in December 2001. One-third of those, including his former finance chief, Andrew Fastow, have pleaded guilty and are cooperating with prosecutors.

Lay said Wednesday in a statement, “I have done nothing wrong, and the indictment is unjustified.”

Government prosecutors have been examining everything from individual business units and shady partnerships to fraudulent tax returns and misguided efforts by Enron’s former accounting firm, Arthur Andersen LLP, to destroy Enron-related documents.

Andersen dominated the first few months of the probe, culminating in its June 2002 conviction for obstruction of justice for destroying documents in late 2001 to thwart a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation into Enron’s finances.

Then the other cases emerged:

• Fastow and his secretive finance unit. Before Fastow pleaded guilty, two of his former top aides — treasurer Ben Glisan Jr. and managing director Michael Kopper — pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges.

Another former executive, Larry Lawyer, pleaded guilty to a tax crime for failing to identify as income money Kopper funneled to him as a “gift.” And three British bankers charged with bilking their former employer of $7.3 million in a scheme engineered by Fastow deny fraud charges and face extradition from London.

• Fastow’s wife, Lea. A former Enron employee, she was indicted last year on six felony counts of conspiracy and filing false tax forms, but in May this year pleaded guilty to a single misdemeanor tax crime for helping her husband hide ill-gotten income. She must begin serving a yearlong prison sentence Monday.

• Alleged manipulation of the California power market in 2000-01 by Enron energy traders. Two former traders, Timothy Belden and Jeffrey Richter, have pleaded guilty to fraud charges and are expected to testify against a third, John Forney, who has pleaded innocent and faces trial in San Francisco Oct. 12.

• Alleged faked earnings in Enron’s defunct broadband unit. Prosecutors also are probing whether some of its executives touted its broadband network as having capabilities it didn’t have to inflate the company’s stock price and pocket millions from sales of shares. Seven former broadband executives named in an indictment that exceeds 220 counts have pleaded innocent and are slated to go to trial in Houston Oct. 4.

• A Nigerian deal in which Fastow played a central role. That case alleges four former Merrill Lynch & Co. executives and two former Enron executives conspired in a sham deal to “sell” electricity-producing Nigerian barges to the brokerage at the end of 1999 to help Enron appear to have met earnings targets. The six defendants have pleaded innocent are slated to face a jury in the first Enron criminal trial on Aug. 18.

Ahead of the Lay indictment, prosecutors moved against former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling and former accounting chief Richard Causey. Both have pleaded innocent.

Their case, to which Lay’s may be joined, contain elements from the Fastow, trading and broadband and barge cases — and seek to place them at the center of the wheel rather than as another spoke.

Prosecutors contend Skilling and Causey knew Fastow ran partnerships that helped Enron hide debt and inflate profits and both secretly promised Fastow his partnerships wouldn’t lose money in deals with Enron.

Prosecutors also say they knew about schemes to conceal broadband losses and mislead investors about the broadband network’s capabilities; Skilling publicly claimed Enron’s California business was small when the company actually pocketed vast profits; both participated in conference calls with analysts during which Skilling painted rosy pictures of money-losing ventures; and Causey knew about the barge deal.

Potential witnesses identified in their indictment include Fastow, Glisan, Kopper, and two other cooperators: David Delainey, former head of Enron’s retail energy unit who pleaded guilty last year to insider trading; and Wesley Colwell, a former in-house accountant for Enron’s trading unit.

Delainey and Colwell, who has not been criminally charged but is cooperating as part of a settlement of SEC allegations, each knew Enron poured trading profits into the retail energy and broadband units to make them appear healthier than they were, according to court filings.

Both also acknowledged that trading profits were hoarded in reserves so earnings would appear more steady.