In Iraqi hands, Saddam faces ‘trial of the century’

BAGHDAD, Iraq – Saddam Hussein, looking thinner after nearly seven months as a U.S. captive, was transferred to Iraqi custody Wednesday, reducing him to a criminal defendant in the land he once ruled and launching the painful process of holding him and his henchmen accountable for their brutal regime.

The former dictator will get his first chance since his capture to speak in public when he appears today before an Iraqi judge. He and 11 of his top lieutenants will hear criminal charges likely to include war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.

President Ghazi al-Yawer told an Arab newspaper that Iraq’s new government has decided to reinstate the death penalty, suspended during the U.S. occupation.

Saddam and the others are no longer prisoners of war but are still locked up, with U.S. forces as their jailers.

The legal proceedings mark the first steps in a process that could take months or possibly years. The trials, not expected to start before 2005, could also widen the chasm among Iraq’s disparate groups – Kurds, Shiites and Sunnis – as the country struggles to recover from a generation of tyranny and conflict.

The transfer of legal custody took place in secret. Salem Chalabi, director of the Iraqi Special Tribunal, said the defendants were brought one by one into a room at an undisclosed location and informed of the change in their status to criminal suspects. They were told that they will appear in court within 24 hours to hear charges, he said.

According to Chalabi, the 67-year-old Saddam looked haggard and thinner after his U.S. confinement. Saddam said “good morning” as he entered the room, listened to the official explanation, and was told he could respond to the complaints today. He was then hustled away.

“Some of them looked very worried,” Chalabi said of the other defendants. They include former Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz, the regime’s best-known spokesman in the West; Ali Hasan al-Majid, known as “Chemical Ali”; and former Vice President Taha Yassin Ramadan.

U.S. and Iraqi authorities hope the trial will lay bare the crimes of the regime – thus vindicating the American decision to invade Iraq last year – and help expunge the nation’s pain and guilt, much as the Nuremberg trials of Nazi criminals did for Germany after World War II.

“It’s going to be the trial of the century,” National Security Adviser Mouwafak al-Rubaie told Associated Press Television News.

“Everybody is going to watch this trial, and we are going to demonstrate to the outside world that we in the new Iraq are going to be an example of what the new Iraq is all about.”

The initial proceedings are taking place under a blanket of secrecy because of fears that insurgents, many of them Saddam supporters, might exact revenge on those taking part.

U.S. and Iraqi officials refused to say where Thursday’s hearing would take place or release the name of the presiding judge. No pictures will be allowed of any of the Iraqi participants – except for the defendants – to protect them from attack. Only a few journalists will be allowed to attend.

Issam Ghazawi, a member of Saddam’s defense team, said he received threats in a telephone call Wednesday from someone who claimed to be a minister of justice who promised that anyone who tried to defend Saddam would be “chopped to pieces.”

U.S. officials had hoped to delay proceedings against Saddam until the Iraqis set up a special court and trained a legal team. But Prime Minister Iyad Allawi, whose government regained sovereignty Monday, insisted publicly on taking legal custody of Saddam quickly. The Americans agreed on condition they keep him under U.S. lock and key.

Trying Saddam and top regime figures presents a major challenge to the Iraqis and their American backers.

Allawi’s government is due to leave office after elections in January, and a second national ballot is to be held by December 2005. That raises the possibility that national policy on the prosecution of Saddam and his backers could change depending on the makeup of the government.

Most of Iraq’s 25 million people were overjoyed when Saddam’s regime collapsed, and many are looking forward to the day he will be punished.

“Everyone all over the world agrees that Saddam Hussein should be put on trial in front of the Iraqi people,” said Baghdad resident Ahmad al-Lami.

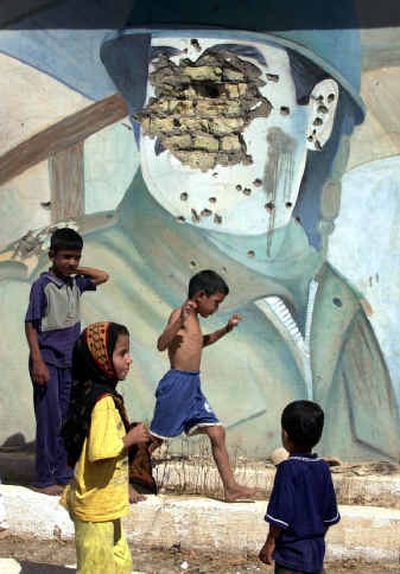

However, the turmoil of the past 14 months has led to a longing for the stability and order of the ousted dictatorship, at least among Sunni Arab Muslims who now feel threatened by the possibility of a Shiite-dominated government.

Nostalgia for Saddam – a Sunni – is strongest in Sunni-dominated parts of the country most heavily involved in the insurgency.

“Saddam Hussein was a national hero and better than the traitors in the new government,” a resident of Saddam’s hometown of Tikrit told APTN, refusing to give his name.

In Fallujah, an insurgent stronghold west of Baghdad, resident Ammar Mohammed suggested the Americans should be put on trial first, because they “killed thousands if Iraqis in one year of occupation.”