UI scientist awaiting results of Titan probe

After sitting through a seven-year space voyage, David Atkinson is finally set for the nail-biting landing of a 700-pound package of instruments on one of the solar system’s most intriguing places.

Atkinson, a University of Idaho computer science and electrical engineering professor, is one of numerous scientists worldwide who’ve developed a series of science experiments onboard the Huygens Probe, a clamshell-shaped aluminum cylinder getting ready to hit the surface of Titan, the largest of 33 moons orbiting the planet Saturn.

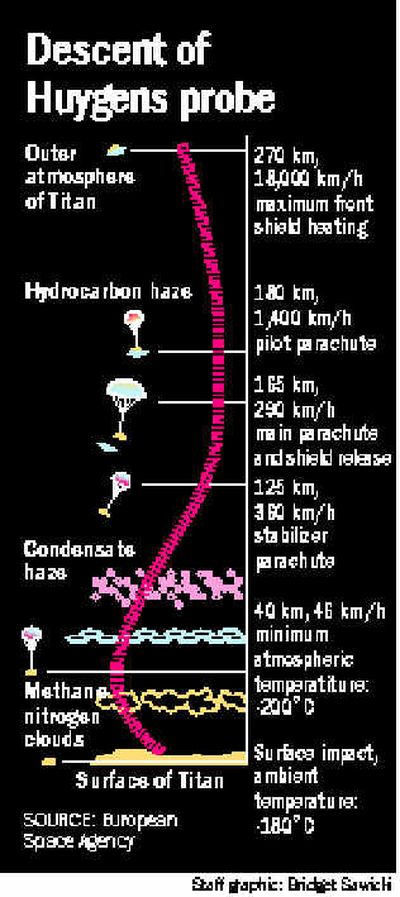

The Huygens probe was launched from Earth in 1997 and earlier this month was placed in orbit around Saturn. In less than three weeks, the probe will start a controlled descent to the surface of Titan, a luminous-orange moon that spins slowly around the huge ringed planet.

Scientists like Atkinson have considered Titan a unique chance to study how planets form and what conditions are needed for the formation of life.

The silver-shelled Huygens probe will begin its 2 ½ hour descent by parachute to the surface of Titan in the early hours of Jan. 14.

Atkinson contributed by designing an experiment to measure the winds in the atmosphere as the probe drops about 780 miles to the surface of Titan.

For those who don’t see spending more than $500 million to study a moon millions of miles away, Atkinson has a quick answer.

“We try to look at different places in the solar system, and if we can understand how a planet’s atmosphere works, that will help us understand how the earth’s atmosphere works,” he said. “We just can’t do these same kinds of experiments here, so we use other planets as our laboratory.”

Titan is the second-largest moon in the solar system and the only moon with an appreciable atmosphere. Titan’s is made up of thick, hazy nitrogen containing carbon-based compounds that could yield important clues about how Earth came to be habitable. The chemical makeup of the atmosphere is thought to be very similar to that of Earth millions of years ago, scientists say.

During the probe’s descent, Atkinson will monitor the Doppler Wind Experiment, a sophisticated tracking process that will track how much the Huygens capsule is buffeted by winds on its way down. The experiment is similar to one that Atkinson developed for the 1995 Galileo probe that entered the atmosphere of Jupiter.

Based on initial tests, the winds should be blowing west to east. They’ll also likely be strongest higher in the atmosphere and decrease nearer to the surface, he said.

“The winds should reach several hundred miles per hour, decreasing to close to zero,” he said. “But you never know. We might even land in a hurricane.”

Atkinson will stay at the UI campus in Moscow until Jan. 7, when he leaves for Germany. He’s officially assigned to the European Space Agency, which is charged with the Huygens experiments. NASA, however, has the initial responsibility of delivering the spacecraft to a descent point above Titan. When it reaches that point, control of the mission transfers from NASA to the European agency, Atkinson said.

Other test equipment aboard the probe will record and transmit data that measure Titan’s magnetic field, atmosphere chemistry and surface conditions.

An onboard camera will gather photo images. The scientific data will be relayed to an orbiter called Cassini that remains in orbit high above Titan. From Cassini, the data will be microwaved back to Earth — a 190-million mile trip that takes about 68 minutes.

The probe will hit the surface of Titan and should continue transmitting data for a while, Atkinson said. It was not designed, however, to continue operating in temperatures of nearly 300 degrees below zero on Titan’s surface. “It might operate for three minutes. It might operate for 30,” Atkinson said.

Atkinson is on a research sabbatical from his teaching responsibilities at the UI. He’s also working on developing an experiment for another space probe. That mission, still on the drawing boards, would take measurements of a moon orbiting the planet Neptune.

Atkinson gives credit to three of his students who’ve been involved in the Huygens experiment. They are Bill Clabough, Erica Lively and Ben Pollard.

Some of the mission scientists will cross fingers during the final descent, but Atkinson said he’ll be fairly confident his experiment will provide good results. “I see a 95 percent range for success in this case,” he said.