Ruling pulls inmates off job

Eric Burdyshaw is losing his job.

Every day for the past six years he has reported to work by 7:30 a.m. His attendance record is good; he’s learned new skills and advanced his position.

Burdyshaw has socked about $9,000 into a savings account and tries to send his sister about $500 each month to help her family bridge tough times. Her husband lost his job with Boeing Co., and every little bit helps, Burdyshaw figures.

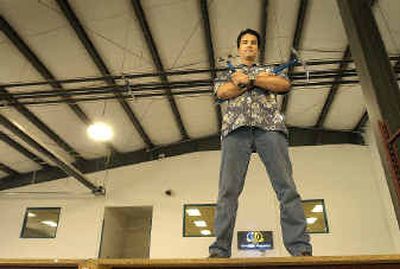

Burdyshaw’s boss, Rob Nadeau, considers him a model employee and a success story. But he has to let him go.

The problem is that Burdyshaw is an inmate at the Airway Heights Correctional Center and works for Omega Pacific Inc. The company is a leading manufacturer of metal rock-climbing safety clips, called carabiners, and has operated inside the prison for eight years. Inmates who work for Omega hone skills as machinists and quality-assurance specialists.

Last week, the Washington state Supreme Court reaffirmed an earlier decision and ruled that allowing private companies to employ inmates violates the state constitution.

The ruling was a victory for business interests who claim the use of inmate labor gives rivals a competitive edge. And it was a victory for organized labor, which argued that every job held by an inmate is one less opportunity for an unemployed, law-abiding resident.

But it has forced Washington’s state prisons to do an about-face on rehabilitation policies originally designed to teach inmates job-market skills and lower recidivism rates, as well as reimburse the state for incarceration and court costs.

About 97 percent of all prison inmates will be released one day. About 24 percent will commit new crimes, get caught and be sent back to prison, said Howard Yarborough, administrator of the state’s Correctional Industries Program. The recidivism rate among inmate workers, however, is about 17 percent, he said.

Omega Pacific now has three months to move its machinery, replace most of its work force, clean out its inventory and restart, without missing an order or letting quality slip. By Thanksgiving, the company will be operating outside the prison walls.

Nadeau decried the court’s decision.

“These are guys who have acknowledged their mistakes, and now they’re trying to take care of the families on the outside,” he said.

At private-industry jobs within the prison, inmate wages are subjected to mandatory deductions.

For every dollar earned, about 15 cents is withheld for incarceration costs; 5 cents is paid into the Crime Victim Compensation Fund; 20 cents is used to pay court fees, fines and restitution; 10 cents is deposited into a mandatory savings account; 20 cents is taken for debts owed for other prison costs, and the remaining 30 cents is net pay that inmates can send to family, spend or save. Omega Pacific pays inmates from minimum wage – $7.16 an hour – to more than $9 an hour.

Members of the company’s inmate work force had varying backgrounds before they were sent to prison.

Some were company CEOs, one was an airline pilot and others were drug dealers and robbers.

“The point is that what they did on the outside doesn’t matter to us as a business,” Nadeau said. “If their behavior inside allows them to work for us, we interview and leave their criminal histories at the door.”

In the company’s noisy machine shop, where inmates use precision machines to cut, bend and shape metal rods into the carabiners that mountaineers and rock climbers entrust their lives to, Burdyshaw and his co-workers had hoped the court would decide prison industries are in the public interest.

For inmate Michael Anderson, working as the lead custodian for Omega Pacific resurrected a sense of pride. He keeps the machine shop floors so clean they shine.

“I’ve been doing something here that helps me stay straight, and something that’s good for all of us,” he said, adding that he dreams of owning his own custodial business when he’s released.

For inmate Ken Galloway, the state Supreme Court decision means he’ll lose a lot more than a job that pays $7.16 an hour.

“This job allowed me to be a more active participant in my son’s life,” he said. “It’s the little things like buying a nice birthday gift.”

Galloway, who measures the breaking point of carabiners, said the job has helped him develop an eye for detail as a quality specialist.

But the court held to a tight reading of the constitution. It originally ruled on the matter, involving a company in Western Washington, in May.

Kris Tefft, a lawyer with the Association of Washington Business, said companies operating inside prisons are given free rent and don’t have to pay the competitive wages and benefits that firms on the outside pay to keep quality workers.

“We know there are two principles at odds here,” he said. “We recognize that rehabilitation is an important social good, but should it come at the cost of the principle of fair competition?”

He said some businesses were losing customers to prison industries. These lost revenues equaled lost jobs for workers.

“It wasn’t fair,” Tefft said.

Omega Pacific is moving ahead.

The company is hiring between 40 and 50 workers to make carabiners at its new manufacturing center south of Highway 2 in Airway Heights. And, as it happens, Omega’s expanding business would have meant the company needed that new facility no matter what the state Supreme Court ruled, sales manager Michael Lane said. But that was planned as an addition to the prison factory, not as a replacement.