Washington Mutual expansion plagued by missteps

For Washington Mutual Inc., the glory days of growth and acquisitions have given way to layoffs and lowered expectations.

The Seattle-based savings and loan, which became the nation’s largest after swallowing three major California thrifts, is completing 13,450 job cuts, closing 100 mortgage offices and shuttering 53 commercial banking branches.

WaMu reported zero income from mortgages in the second quarter, compared with $611 million last year. Overall profit was down 49 percent. And its share price has dropped 12 percent since May, closing Tuesday at $38.88 on the New York Stock Exchange.

What went wrong? A national decline in mortgage lending, a business in which WaMu is No. 2 behind Wells Fargo & Co., is partly to blame. But at Wells Fargo and Countrywide Financial Corp., the third big home lender, second-quarter net income still managed to rise.

Banking industry analysts point to a series of management missteps, including:

• Too-rapid expansion in the last decade, including the takeovers of California’s American Savings, Great Western Bank and Home Savings, plus four mortgage companies, that kept WaMu from smoothly integrating disparate accounting systems.

• Botched use of financial hedges, investments that were supposed to offset the risk of servicing its $7.5 billion in mortgages.

• Trouble fixing billing errors, misplaced loan payments and other banking foul-ups, leading to an unusually heavy volume of complaints for a major bank, especially one that boasts of its in-branch service.

“It’s the classic story of growing really fast and not having the management and infrastructure to keep up,” said Michael Perry, chairman of Pasadena, Calif.’s IndyMac Bancorp, a mortgage lending rival that has stressed internal growth instead of acquisitions.

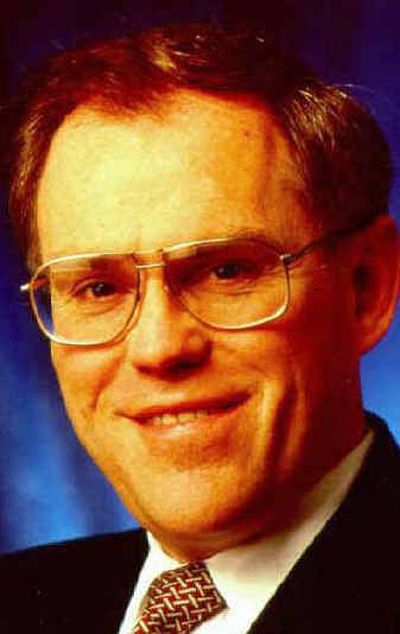

WaMu’s president and chief executive, Kerry Killinger, has acknowledged the seriousness of the problems.

“I know many of you are unhappy,” he told analysts recently. “I understand your concerns, and as a significant shareholder I am not happy either.”

Killinger, who declined to be interviewed for this story, told the analysts that WaMu became distracted during the home refinance boom, a three-year stretch in which it vied with San Francisco’s Wells Fargo and Countrywide in Calabasas, Calif., to be No. 1 in mortgage loans. He said sky-high costs resulted from an inability to get nine aging computer systems working together and the failure of a plan to replace them.

He said his priorities today were to slash costs at the once-profitable mortgage business and to work with consultant BlackRock Inc. on the financial hedges.

So far, Wall Street isn’t impressed. WaMu shares have been virtually flat this year and are up just 4.6 percent in the last two years. That contrasts with a 24.5 percent increase for the BKX index of 24 banks and thrifts and a 160.1 percent boost for Countrywide.

The stock would be in worse shape, some analysts believe, except for WaMu’s hefty 4.5 percent annual dividend and rumors that a goliath such as New York’s Citigroup Inc. or Britain’s HSBC Holdings could acquire the S&L. Securities analysts have issued a dozen downgrades to WaMu ratings since November and only one upgrade.

“The stock basically has gone nowhere for the past 3 1/2 years,” said Charlotte Chamberlain, a Jefferies & Co. analyst in Los Angeles who rates the company “underperform.” Chamberlain argued that WaMu’s board would serve shareholders best by selling the company or at least giving Killinger the boot.

WaMu dismissed that advice, saying in a statement: “The board recently approved a five-year plan for Washington Mutual and reaffirmed its confidence in the management team to execute that plan.”

The strategy includes as many as 18 months to fix the mortgage business, which last month got its third top executive in less than a year. Killinger is also searching for a new chief financial officer for the unit.

WaMu has strengths, including an apartment-lending operation that is No. 1 in the country and 1,800 retail offices in 15 states. (It is so proud of the offices’ customer-friendliness that it has patented their design).

What’s more, WaMu has few bad loans on its books, although analysts will watch for the effect of rising interest rates on its portfolio of adjustable mortgages.

WaMu is No. 2 in deposits in Washington and Oregon and has a significant presence in New York, Texas and Florida. It is No. 3 behind Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo in California, by far its biggest market, where it employs about 20,000.

The retail bank reported second-quarter profit of $508 million, up 25 percent from the same quarter in 2003. For the company, it’s the “crown jewel,” said Brad Davis, WaMu’s executive vice president and chief marketing officer.

Overall second-quarter profit was $489 million, compared with $995 million in 2003.

The mortgage bank’s troubles certainly aren’t in volume of business. The unit originated 11 percent of all U.S. home loans last year and was the No. 1 mortgage servicer, mailing statements to and collecting payments from nearly 5 million homeowners.

But WaMu warned in June that the unit’s earnings would plunge from $1.3 billion in 2003 to perhaps zero this year. The second-quarter results were ugly indeed. Besides the zero overall profit in home loans, the mortgage bank’s loan volume for the period totaled $59.5 billion, down from $106.7 billion in 2003, in part because its systems were so inefficient that it had to pass up some business.

During the call with analysts, Killinger asked for patience.

“We have a great franchise, we have the right strategy,” he said. “The path may not be perfectly smooth through the coming months, but we are going to execute on that strategy.”