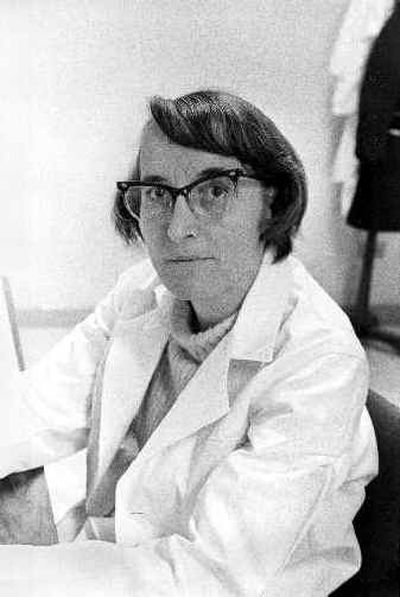

Kubler-Ross, ‘On Death and Dying’ author, dies

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, the Swiss-born psychiatrist whose groundbreaking study of the end stages of life humanized the treatment of the terminally ill and helped to inspire the hospice movement in the United States, died of natural causes Tuesday in Scottsdale, Ariz. She was 78.

Kubler-Ross had been in declining health since 1995, when she suffered a series of debilitating strokes. Surrounded by family and friends, she died at an assisted living center where she had lived for the past few years, her son, Kenneth, said on Wednesday.

“For her, death wasn’t something to fear. It was like a graduation,” he said Wednesday.

In a 2002 interview with The Arizona Republic, she said she was ready to die: “I told God last night he’s a damned procrastinator.”

She felt that way until the end. But she made sure to enjoy her last moments by smoking cigarettes from Sarah Ferguson, Britain’s Duchess of York, and by eating Swiss chocolates and shopping, said Ross.

“Death is simply a shedding of the physical body like the butterfly shedding its cocoon. It is a transition to a higher state of consciousness where you continue to perceive, to understand, to laugh, and to be able to grow,” she once said.

Kubler-Ross was the author of “On Death and Dying,” a 1969 best seller that illuminated the emotional life of dying patients by identifying five stages of the dying experience: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. The book, which has been translated into more than 25 languages and is still a widely used text, spurred a revolution within the medical community to lift the taboo on discussions of the dying and infuse their treatment with dignity and affection.

“Prior to Elisabeth’s work, patients who were dying were objectified, seen as a collection of manifestations of disease,” said Dr. Ira R. Byock, a longtime hospice physician and past president of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

“She forced the medical profession and health care in general to listen to the person who was confronting the end of life. This was a radical notion … one that medicine sorely needed to hear.”

Dr. Joanne Lynn, a senior scientist with RAND Health, a nonprofit research enterprise based in Santa Monica, Calif., who also directs the Washington Home Center for Palliative Care Studies in Washington D.C., said: “Her biggest legacy is just to have us notice that there really is a piece of time when it is reasonable to take notice of the fact that time is likely to be very short and to treat that phase of our life somewhat differently… . She gave us the tools – and most of all, the courage – to notice the obvious.”

In later years, Kubler-Ross directed her attention to AIDS patients, particularly infected babies, trying to improve their care at a time when the disease was little understood.

Then, in the 1980s, she took a direction that startled many in the medical community: exploring “out-of-body” experiences and other phenomena reported by people who had come close to dying. She began to speak of contacts she said she had with spirits. Death, she seemed to be suggesting, was just another phase to be surmounted.

Such reports caused some of her colleagues in the medical profession to doubt her sanity. But the feisty “death and dying lady,” as Kubler-Ross came to be known, did not attempt to foist her unconventional views on others, arguing that skeptics would one day finally experience the truth for themselves.

Kubler-Ross was born in Zurich on July 8, 1926, the smallest of a set of triplets (“a 2-pound nothing,” she called herself later) who was not expected to live. But, proving herself a rebel from birth, she survived.

She had a difficult childhood under the thumb of a domineering father. One of her earliest memories was of her father forcing her to take her pet rabbit to the butcher, then watching her family “eat my bunny” for dinner. That incident taught her to be tough – “tougher than anyone” – she recalled in her 1997 memoir, “The Wheel of Life.”

She left home at 16 and found various jobs, including work as an assistant in an eye clinic. She also volunteered at a Zurich hospital, helping refugees from Nazi Germany.

After World War II, she was a cook, mason and roofer. She hitchhiked across Europe helping establish typhoid and first-aid clinics. Visiting with concentration-camp survivors and refugees, including one memorable stop at Majdanek, a Nazi concentration camp in Poland, persuaded her to pursue medicine.

Kubler-Ross graduated from medical school at the University of Zurich in 1957. She met Emanuel Ross, a Jewish-American doctor there, and they married. They moved to New York the following year.

Her work with the dying began at the University of Colorado medical school, when she was asked to take over the lecture course of a respected professor. Desperate for a topic that she hoped would keep her students from falling asleep, Kubler-Ross chose “the greatest mystery in medicine,” death.

To her surprise, she discovered a lack of material on the subject and wondered how she would fill a two-hour lecture. On rounds one day, she found her answer in a 16-year-old girl dying of leukemia who had freely and eloquently expressed her anger at her family’s inability to cope with her impending demise.

Kubler-Ross was fascinated by the girl and knew that her students would be too. “Tell them all the things you could never tell your mother,” she said when she asked the girl to address her class. “Tell them what it’s like to be 16 and to be dying. If you are furious, get it out. Use any kind of language you want. Just talk from the heart and soul.”

The girl poured out her feelings and left her audience in tears.

Kubler-Ross spent most of her time writing and lecturing, giving “Life, Death and Transition” workshops around the world.

Starting in the 1970s, Kubler-Ross’ work with dying patients led her to explore the idea that life after death may be a reality.

She began emphasizing her belief in reincarnation and a spirit world. She interviewed patients who had returned from near-death experiences. They told of being in contact with long-dead relatives who spoke of seeing a light at the end of a tunnel.

As with her famous stages of dying, she theorized that humans experience four stages of actual death: floating out of the body; being converted to a form of spirit and energy; being guided by a guardian angel through a transitional phase; and finally a meeting with the Highest Source, or God.

Although she did not found the hospice movement, her work spurred the development of hospices, providing what Byock called “a theoretical foundation for end-of-life care.” There are now more than 3,100 hospice programs in the United States.

She insisted that doctors and nurses treat the dying with respect and dignity.

She also insisted that patients should have a choice about where to die and an opportunity to participate in the decisions doctors were making about their lives.

Kubler-Ross wrote 12 books after “On Death and Dying,” that focused on such topics as the AIDS epidemic and coping with the death of a child.