Munson touched many lives

BRADENTON, Fla. — They stood with heavy hearts and their caps placed over those hearts, held tightly by their right hands.

The manager, the coaches and the players not in the lineup lined the top step of the dugout. The starters, with the exception of Jerry Narron, were out on the field at their positions. Narron was the catcher. He remained near the dugout, lacking the will to stand in the one place in New York that truly belonged to Thurman Munson — the dirt behind home plate at Yankee Stadium.

Munson was the Yankees’ catcher who died the day before when the Cessna Citation he owned and piloted crashed and burned 600 feet short of the runway at the Akron-Canton Regional Airport. It was an off-day, the team’s first after 14 straight games, and Munson was at his home in Canton, Ohio, stealing some hours from the long season to spend time with his family. He decided on a whim to show off his new jet to a pair of friends and practice touch-and-go landings.

There were problems when Munson tried to land for the fourth time. The descent was too sharp, and he could not pull the jet out of the dive.

Pilot error, it was later ruled.

Munson died from his injuries.

His friends suffered severe burns but survived.

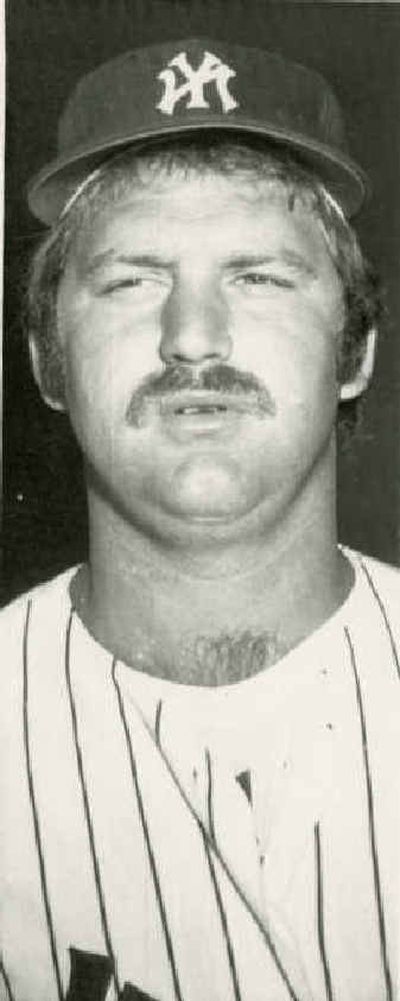

Munson was an All-Star, the American League Rookie of the Year in 1970, the league MVP in 1976 and the backbone of the Yankees’ World Series winning teams of 1977 and 1978.

He was also the Yankees’ captain, their first since Lou Gehrig.

Now, those at Yankee Stadium — all of New York it seemed — stood at attention as Bob Sheppard, the stadium’s public address announcer, asked for a moment of silence.

It lasted for only a moment. Then someone began to clap, and then another and another until the fans — 51,151 strong — charged the humid night air with a thunder that can still be heard 25 years later by those who were there.

“Goosebumps,” Tampa Bay Devil Rays manager Lou Piniella said. “I had goosebumps.”

Piniella played left field for the Yankees that night. He was one of Munson’s closest friends.

Sheppard tried to quiet the crowd but wisely gave up. The fans had something to say.

The ovation lasted nine minutes.

Bucky Dent, the shortstop, raised his sleeve to his cheek.

Reggie Jackson, the right fielder who often verbally sparred with Munson, wept, his head bobbing as he sobbed.

Graig Nettles, the third baseman, remained perfectly still.

Nine minutes.

“It was really bone shaking,” former umpire Rich Garcia said. “It was really emotional. I don’t even know how the guys could even play. Most of the players were in tears.”

Garcia, who now lives in Clearwater, worked the game. He and the rest of the crew stood shoulder-to-shoulder 30 feet up the third base line.

The area around home plate remained vacant, a tribute from the rookie Narron.

Pitcher Ken Clay, who was in his third season with the club, stood atop the dugout steps, alongside pitcher Rich Gossage.

“It chilled you,” said Clay, who now lives in Bradenton. “Especially when they put his picture on the scoreboard, and it hit you, he wasn’t coming back.”

Slowly, the stadium quieted enough for Sheppard to be heard.

“Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for your wonderful response,” he said.

Narron ran out to his position. The game started. The Yankees lost to the Baltimore Orioles 1-0.

Family man

Thurman Munson died 25 years ago Monday (Aug. 2).

He died because he loved his family so much, he wanted to keep them away from New York City and back in the dream house he and his wife, Diana, had built in Canton. He died because he wanted to be the kind of father his father wasn’t.

Darrell Munson was a long-distance trucker who spent a great deal of time away from home. As a result, his relationship with his son, Thurman, was strained.

Thurman Munson wasn’t like that. He smothered his three children with affection. Diana was the disciplinarian.

Munson missed his family during the season when he was in New York and they were back home, growing up while he performed for the children of strangers.

The solution was a plane. Munson could fly home the night before an off day, spend the entire day with Diana and the kids, and fly back the morning of the next game.

What could be better?

Munson bought the Cessna Citation three weeks earlier for $1.4 million.

In hindsight, the Cessna was too powerful for Munson, who had been flying for less than two years. It was a jet, and it reacted differently than any of the three propeller crafts Munson had owned.

Piniella had flown with Munson before. So had Bobby Murcer, another of Munson’s closest friends on the team.

Two nights before the crash, while the Yankees were in Chicago to play the White Sox, the three teammates spent the night at Murcer’s apartment. They talked about everything, including Munson’s flying.

“We were actually trying to convince him to get rid of his jet,” Piniella said. “How about that?”

Pilot error

Munson played first base during what would be his final game. He walked in the first inning, struck out in the third and took himself out of the game because his knees ached.

The Yankees won 9-1, and afterwards, Munson tried to talk Murcer into flying with him back to Canton. Murcer declined but drove Munson to the airport. He stood by the runway and watched his teammate take off, looking up as the jet screamed directly overhead and off into the night.

Munson met Jerry Anderson, a friend, at the airport the following afternoon and talked him into going up while he practiced touch-and-go landings. David Hall, Munson’s flight instructor, joined them.

On his fourth approach, Munson was directed to use runway 1-9. He encountered problems, though, as he neared the airport. According to the crash report by the National Transportation Safety Board, the jet was descending too quickly, the landing flaps weren’t down, and he was flying too slowly. The plane stalled, and Munson couldn’t correct the problems.

The jet clipped the top of some trees. A wing was ripped off.

They hit the ground 870 feet from the runway, skidded into a ditch and slammed into a tree stump near Greensburg Road, not 10 miles from his home.

Munson turned to his friends and asked, “Are you guys OK?”

They were, but Munson said he couldn’t move. They tried to free him, but flames and smoke soon engulfed the cockpit.

Munson lost consciousness, and Anderson and Hall, realizing their own lives were in danger, escaped through an emergency exit. They suffered second and third degree burns.

At 4:02 that afternoon, Munson was pronounced dead at the scene.

He was 32.

Thurman was Thurman

The phones began ringing early that evening.

“Thurman is dead.”

At first, Clay thought it was a prank. He didn’t recognize the caller to be Gerry Murphy, the Yankees’ assistant traveling secretary.

Murphy called back, identified himself and repeated the news.

“Listen,” he said, “Thurman has just been killed in a plane crash.”

“I was dumbfounded,” Clay said. “I started calling my teammates. ‘did you get the call?’ They’d say, ‘Yeah.’ We couldn’t believe it.”

The Kansas City Royals were at the airport waiting to board a charter for Detroit when they heard the news.

“We were shocked,” said Hal McRae, then a member of the Royals. “I didn’t even know he had a plane. Nobody flew in those days.”

Sounded crazy.

“Thurman was Thurman,” Clay said. “He was going to do it his way.”

At 5-foot-11, 190 pounds, Munson fit his bulldog image. He was a relentless competitor, playing the 1978 World Series with a dislocated shoulder.

“He talked a lot (behind home plate),” McRae said. “I remember telling the umpire to tell him to shut up. He tried to break your concentration by telling you how tired you looked or that you were in a slump… .

He was fun to play against because he would do anything to beat you.

“He was an exceptional player. There was nothing he couldn’t do. He was rough and tough. He played every day, and he enjoyed playing. He’s the guy you wanted for a teammate. He irritated me, but that’s because he was such a competitor.”

Munson, with his walrus mustache and wad of tobacco in one cheek, wore a gruff exterior. He wasn’t friendly to the press. He didn’t trust those in the front office. He heard the insults over the praise.

“I’d like to see him get a hit in his first time up, otherwise he would be grumpy all day,” Garcia said. “I got along fine with Thurman. He said he liked me because I was the only one in the league who was shorter than he was.”

Former Yankees president Gabe Paul said it was all an act.

“Thurman Munson is a nice guy who doesn’t want anyone to know it,” Paul once said.

“That’s absolutely true,” Clay said. “He didn’t like to speak to a lot of people. He wasn’t shy. He just didn’t like that part (of being a baseball player). But when we needed something, he was the guy for the moment. If we needed a home run, he’d hit the home run. Move a runner?

He’d move a runner. Whatever the situation called for, you know Thurman had it in his mind.”

Murcer’s tribute

The funeral was held Monday, Aug. 5. The Yankees charted a plane to Canton so they could be there for Diana and help bury their friend in the morning and be back at Yankee Stadium for the final game of the four-game series with Baltimore.

“I was surprised they played,” said Garcia, who attended the funeral with crew chief Bill Haller, then returned to work the game. “They had to be emotionally worn.”

They were.

“It was a very, very, very draining day,” Piniella said.

The Yankees looked flat that night, and Baltimore led 4-0 after six innings.

Then Murcer took over. He hit a two-out, three-run homer in the seventh and drove in the trying and winning runs in the bottom of the ninth with a single to left.

“We really wanted to win that ballgame for Thurman,” Piniella said.

“Bobby was probably as close to him as anybody on the team, so he got it done.”

The reality

The Yankees immediately retired Munson’s No. 15, and his locker was quickly made into a monument that, to this day, remains unchanged.

“It’s real neat to go into the clubhouse and see that every day,” said Rays first baseman Tino Martinez, who played with the Yankees from 1996-2001.

The locker holds Munson’s equipment, his catcher’s mask, shin guards and familiar orange chest protector, and his uniform, just as it had the afternoon of Aug. 3, 1979, when Piniella and the rest of his teammates filed into the clubhouse hoping it was all a bad dream.

“The strangest thing about that whole time was coming to the ballpark the first day (after Munson’s death) and seeing his empty locker with mask and his uniform,” Piniella said. “It was a little eerie.”

Today, the locker is just one of many shrines to past Yankees found at the stadium.

“Back then, it was a friend and a teammate,” Piniella said.

Nine minutes has stretched across 25 years.

For those who knew Munson, for those who were there that night in the Bronx when the fans said their goodbye, the goosebumps still remain.