Weaver surrenders at Ruby Ridge

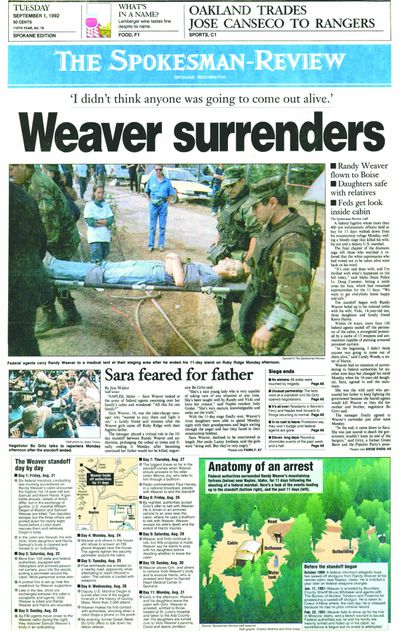

A federal fugitive whom more than 400 law enforcement officers held at bay for 11 days walked down from his mountaintop refuge Monday, ending a bloody siege that killed his wife, his son and a deputy U.S. marshal.

The final chapter of the dramatic saga left those who watched it relieved that the white supremacist who had vowed not to be taken alive went back on his word.

“It’s over and done with, and I’m thrilled with what’s happened on the hill today,” said Idaho State Police Lt. Doug Camster, letting a smile cross his face, which had remained expressionless for the 11 days. “We want to get everybody home happy and safe.”

The standoff began with Randy Weaver holed up in his isolated cabin with his wife, Vicki, 14-year-old son, three daughters and family friend Kevin Harris.

Within 24 hours, more than 100 federal agents sealed off the perimeter of the cabin, a stronghold protected by a cache of 15 weapons and ammunition capable of piercing armored personnel carriers.

“In the beginning, I didn’t think anyone was going to come out of there alive,” said Candy Woods, a sister of Harris.

Weaver had no intention of surrendering to federal authorities for another nine days but changed his mind Monday when his 16-year-old daughter, Sara, agreed to end the stalemate.

She was the wild card who persuaded her father to keep fighting the government because she feared agents would kill Weaver as they did her mother and brother, negotiator Bo Gritz said.

The teenager finally agreed to Weaver’s surrender just after noon Monday.

“In the end, it came down to Sara. She was just scared to death the government wouldn’t keep its end of the bargain,” said Gritz, a former Green Beret and the Populist Party’s presidential candidate.

Despite a bullet wound in his shoulder, Weaver, with his head shaved, carried his 10-month-old daughter Elisheba and held Gritz’ hand as he walked to waiting federal agents. Sara and her 10-year-old sister Rachel clutched the hands of Gritz aide Jack McLamb and trailed their father down Ruby Ridge.

Within a short time, authorities flew Weaver from Sandpoint in a white Sabreliner jet to Boise, where he will stand trial. U.S. marshals rushed him to a downtown hospital about 5 p.m. for a check-up and then to the Ada County Jail, the Boise-area holding facility for federal defendants.

He is scheduled to appear in federal court at midday today.

FBI Supervisor Gene Glenn said a special team of FBI agents is conducting a separate probe of the shooting. Ballistic experts from the FBI laboratory in Washington, D.C., were called to Naples to reconstruct the shootings of 14-year-old Samuel Weaver and his mother, who died in her doorway when a sniper’s bullet hit her in the head.

“There are a lot of thanks in order as we are wrapping this thing up,” Glenn said, praising the U.S. Marshal Service, the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, the Idaho State Police and the Boundary county Sheriff’s Department for their roles.

“The key line is there has been restraint,” Glenn said.

Duke Smith, associate director of the Marshal Service, defended the size of the operation which involved about 400 federal and state officers.

“Any time that you lose one of your own, which we did 11 days ago, it’s important that you marshal all the effort that you can in the collective way to bring something like this to a conclusion,” Smith said.

In the Selkirk Mountains, three girls who lost their mother, their brother and – now their father to the courts – were staying with relatives and may later live with friends in the area.

Federal authorities promised the girls in a note that helped end the standoff that they could return to the cabin by Sept. 7, after evidence is processed. It was not clear whether the girls will live there or just visit.

After being airlifted to Sacred Heart Medical Center on Sunday, Harris was advised of his rights by U.S. Magistrate Cynthia Imbrogno during a 15-minute hearing.

Between medical examinations in the hospital emergency room, Imbrogno told Harris he faced a possible death sentence if convicted of first-degree murder.

On the day that the siege began, six U.S. marshals stalked the woods near Weaver’s cabin, gathering information they needed before trying to apprehend the man who had eluded them for 18 months.

In October 1989, Weaver allegedly sold two sawed-off 12-gauge shotguns to a federal informant. He was indicted more than a year later on charges of possessing illegal firearms.

It was another year before U.S. Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents and Boundary County Sheriff Bruce Whitaker could catch Weaver. The fugitive and his wife were arrested when they left the cabin for supplies in January 1991.

But Weaver was released the next day and he and his family had not left the cabin since. After he missed his court date in February 1991, marshals began watching his mountain fortress.

Gritz said after he and McLamb searched the family on Monday, they left behind extensive ammunition and 15 semiautomatic weapons. In the cache were about five pistols, four shotguns and six rifles, including the one that Harris says he used to fire one of the first shots beginning the standoff Aug. 21, killing Deputy U.S. Marshal William Degan.

Every day that passed brought more Weaver supporters and protesters to the dusty roadblock at Ruby Creek, 40 miles south of the Canadian border. By midweek, Gritz joined them, offering to talk down from the mountain his fellow Green Beret.

Gritz walked down to the roadblock just about 2:30 p.m. Monday and waded into a crowd of protesters, giving them a Nazi salute that he had promised Weaver and telling them the standoff was over.

Earlier in the day, he told Weaver sympathizers that Weaver would be down by noon. He attributed it to a vision he had at 2:30 a.m. Monday.

“It’s over. All the family is out and safe,” he said, crediting the surrender to “God Almighty” and the prayer vigil of Weaver’s supporters who manned a roadblock, waving anti-government signs and singing hymns for 11 days.

As the siege ended, about 25 protesters remained at the roadblock.

“It’s just not what we expected,” said a young skinhead, who sat quietly on a stump. “I wish he’d taken a few more out.”

When Gritz and McLamb made it to the cabin at about 9:30 p.m. Monday, Weaver told them he would not even discuss surrendering until Sept. 9. He arrived at the date through the Bible and by calculating numbers in the Scriptures, Gritz said.

After Gritz passed a note under Weaver’s door that said, “The battle is in the courts, not up here,” the negotiations began anew.

Part of the government agreement was that the Weavers walk down off the mountain with dignity, and without agents or handcuffs, Gritz said.

“The guys (agents) on the hill were exceedingly understanding for Randy as a widower,” Gritz said. “If we hadn’t gotten him out today, there would have been more loss of life.”

Before his surrender, Randy Weaver “was very concerned for his safety,” the FBI’s Glenn said. “We made a very concentrated commitment to providing him adequate safety and security. That will be followed not only to the letter of the agreement, but in the spirit in which it was negotiated.

“This was a monumental, negotiated effort,” Glenn said.

Late Monday Weaver neighbor Tony Brown said federal agents also learned compassion from the tragedy.

“This had a big impact on these agents’ view of things. They picked up a little bit on the waste and loss of life. I don’t think they are gung-ho killers.”

When asked what Glenn would like to say to protesters and others who are upset that a mother and her son were killed in the ordeal, Glenn said: “The message that I would like to say is, ‘We are very sorry.’ The situation that has transpired – we talked before – is not a ‘win’ situation. We early on discussed the fact that there are no winners in a situation with all this sadness.”

Staff writers J. Todd Foster, Kevin Keating, Dean Miller, William Miller, Bill Morlin and Jess Walter contributed to this report.