Hanford Site Public Tour

Thousands of tourists visit Hanford Nuclear Reservation each year, taking advantage of free bus tours provided by the U.S. Department of Energy to learn more about the history and cleanup of North America's most polluted site. The tours are so popular that they fill up shortly after they open in late February.

Section:Picture story

The Hanford Site tour bus passes the Columbia Generating Station off in the distance. This facility is not owned or operated by the Department of Energy. It is operated by Energy Northwest on land leased from DOE. It produces approximately 1,170 megawatts of electricity, equivalent to about 10 percent of Washington’s power and 4 percent of all the electric power used in the Pacific Northwest.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Forty years of plutonium production at the Hanford Site has yielded a challenging nuclear waste legacy-approximately 56 million gallons of radioactive and chemical wastes stored in 177 underground tanks (tank farms) located on Hanford’s Central Plateau. The mission of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of River Protection (ORP) is to address the risks posed by this tank waste through immobilization of the waste, and the ultimate closure of the tanks and decommissioning of the treatment facilities.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

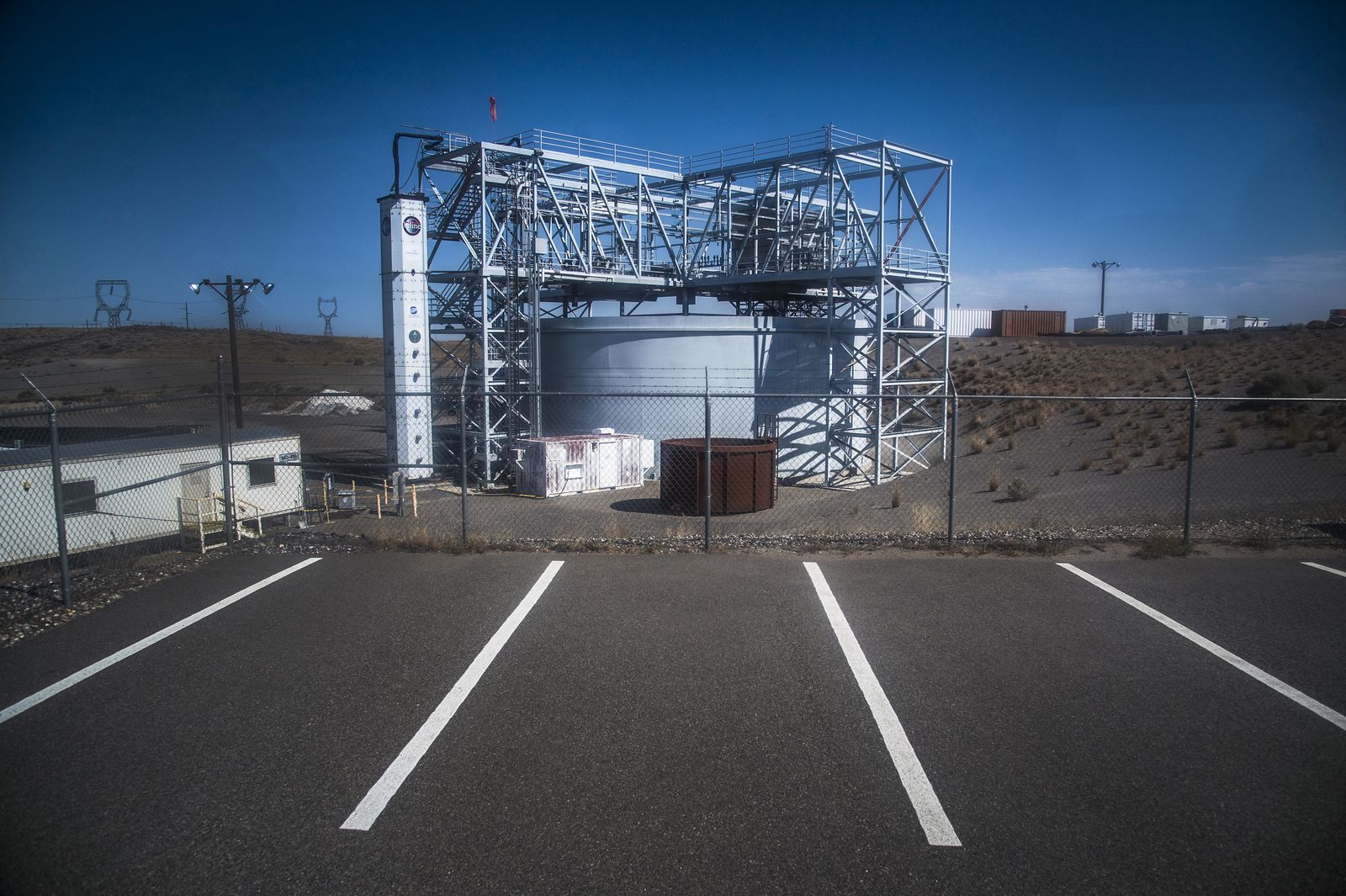

Hanford’s Cold Test Facility, is a scaled version of one of Hanford’s 177 underground nuclear waste storage tanks. Hanford crews designed and built the innovative Cold Test Facility (CTF) to develop ways to remove the waste from the tanks, without having to subject the workers or the equipment to the radioactive environment found in the tanks on the Site. The Cold Test Facility is a full-scale mockup of a single shell storage tank at Hanford, with the height, weight, and riser dimensions exactly the same as they are found on the Site. Workers can simulate the kinds of conditions that would be found inside a tank, while also testing new equipment and technologies which they believe could help remove tank waste that is in difficult-to-reach places or in a semi-solid state.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

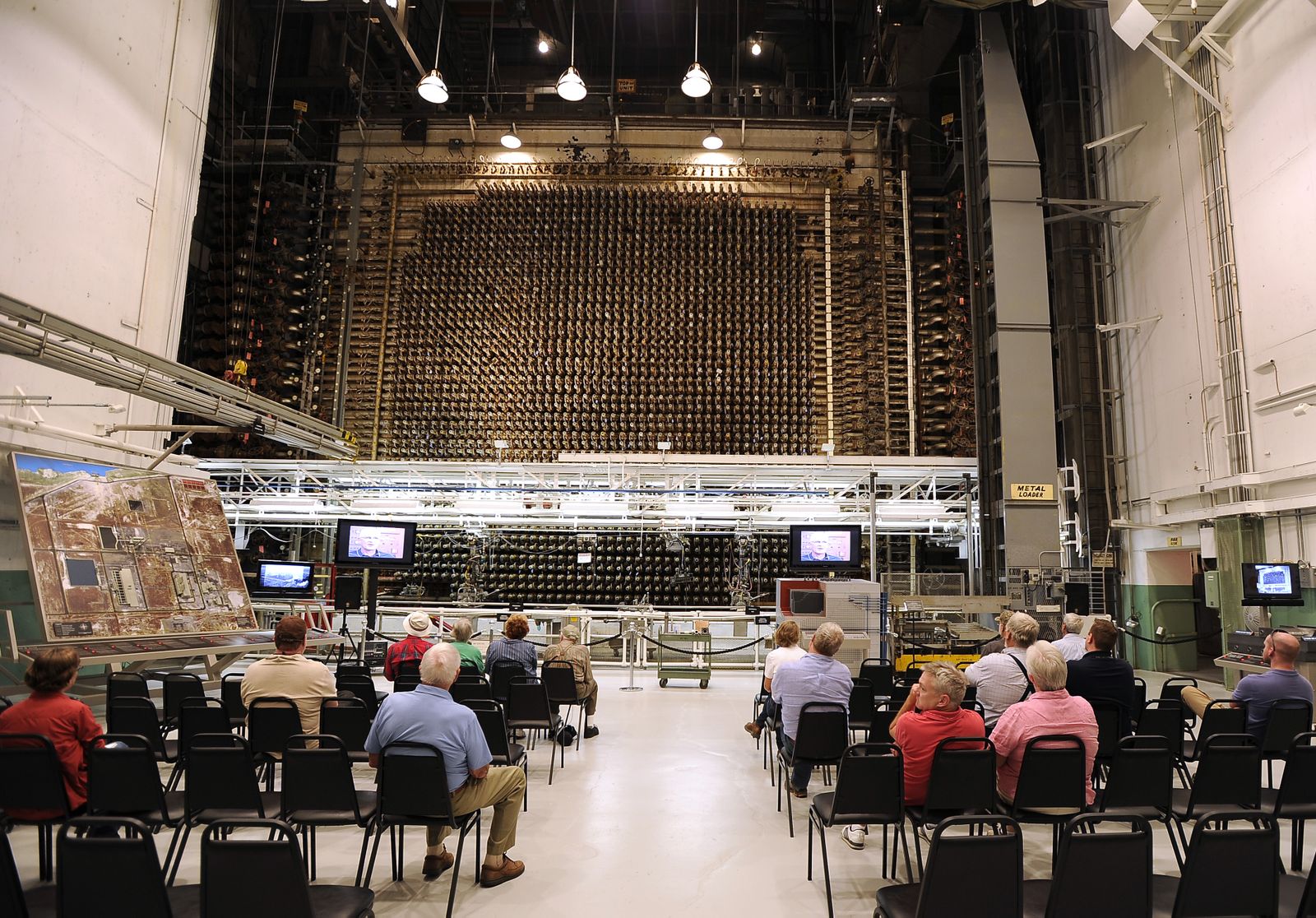

The B Reactor is being preserved and is open for public access during tours. The reactor has been designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. Department of the Interior. The reactor was the world’s first full-scale plutonium production reactor and produced plutonium for the first atomic bomb detonation (Trinity test) and the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan during World War II.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Inside the historic B Reactor, the world’s first full-scale plutonium production reactor, Hanford Site Public Tours participants watch a video presentation while sitting in front of the deactivated reactor core where uranium was irradiated to produce plutonium used in the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

A 1940’s era office at the historic B Reactor.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

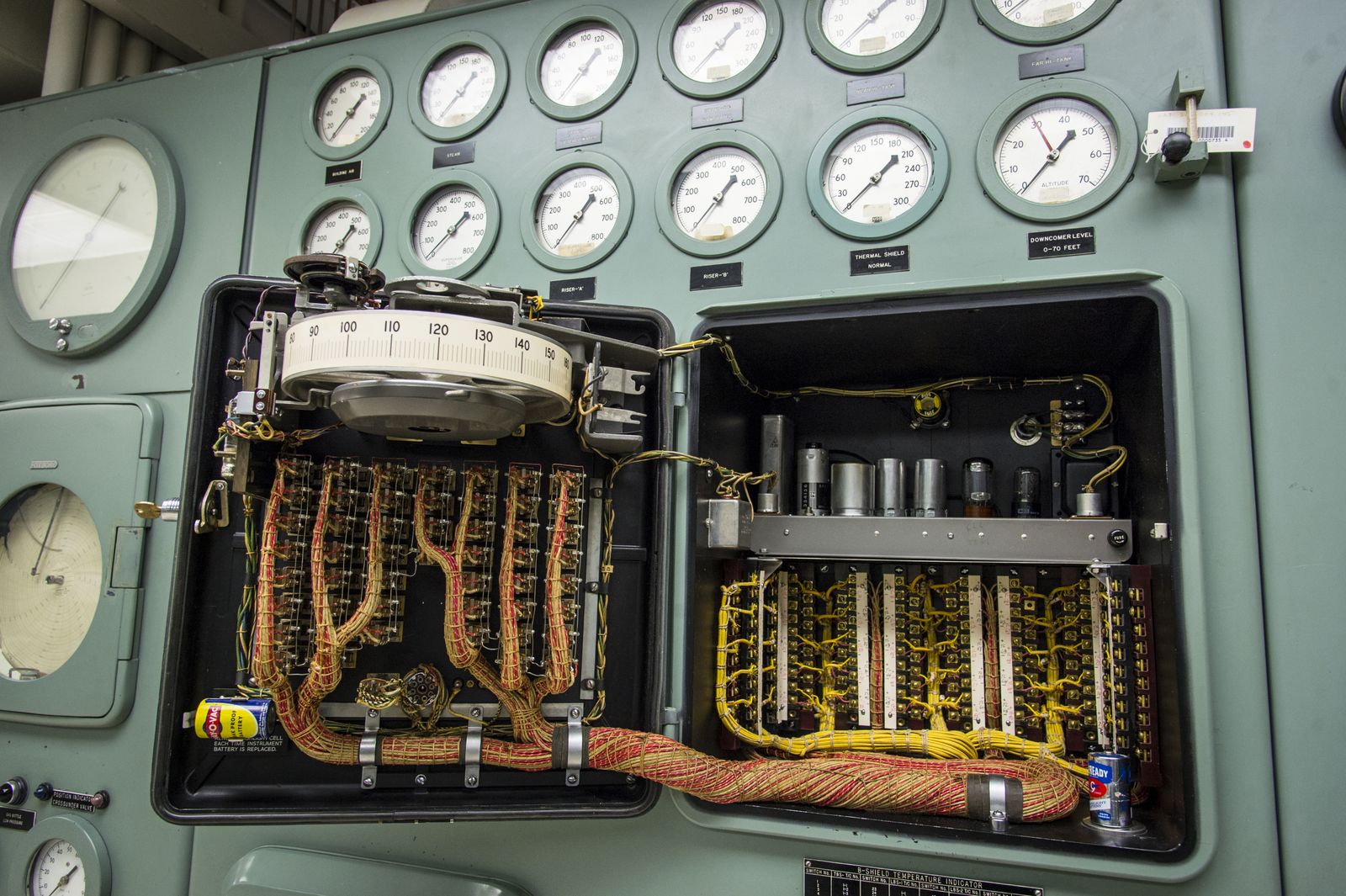

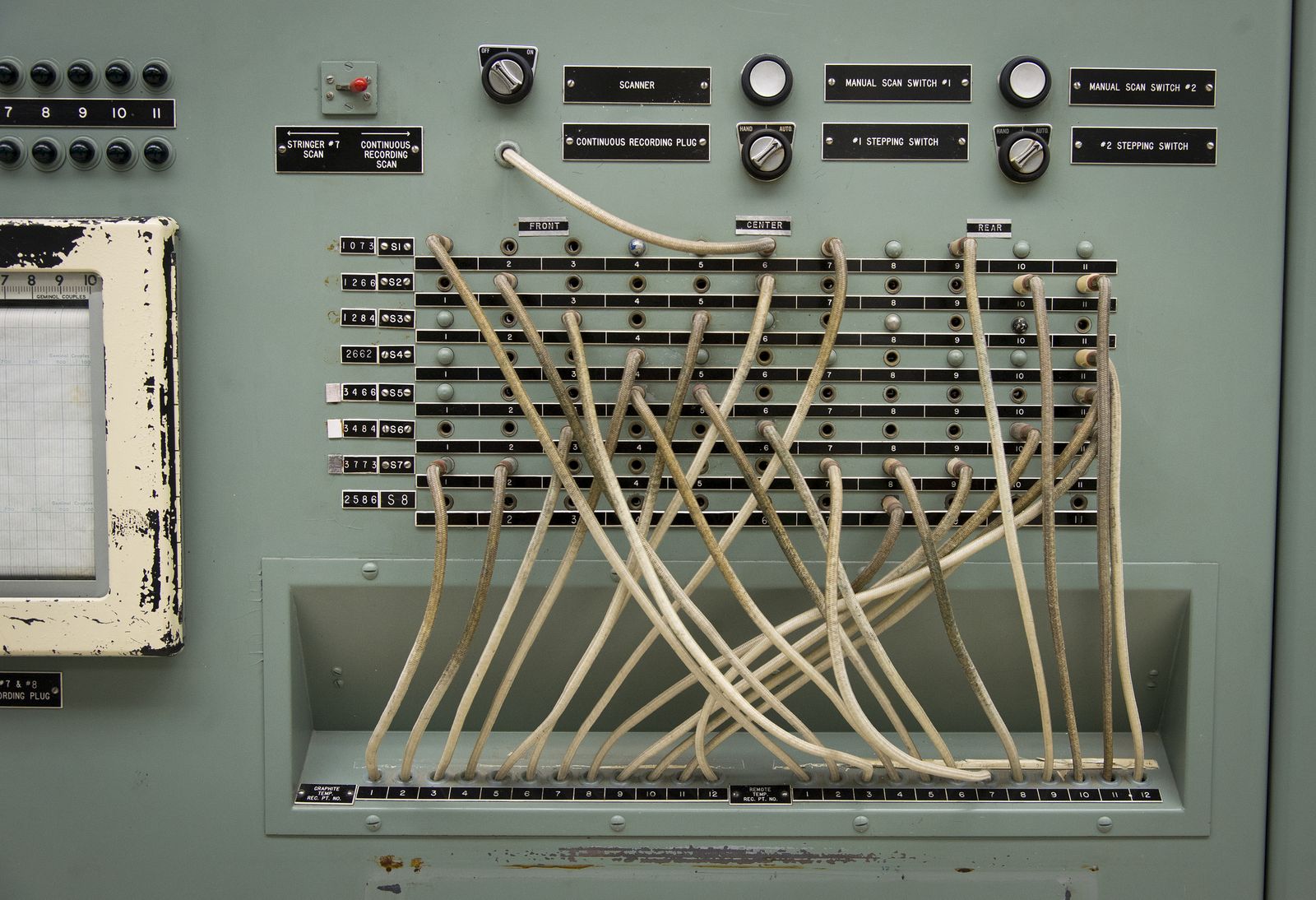

Many of the instruments in the B Reactor control room were built onsite and had never been used in an industrial setting prior to the creation of the reactor.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

The operators of the B Reactor manipulated control rods through this control panel to ensure the smooth operation of the reactor. The gauges on the panel and covering the wall of the control room allowed operators to monitor temperature, pressure and power levels throughout the reactor core.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Many of the instruments in the B Reactor control room were built onsite and had never been used in an industrial setting prior to the creation of the reactor.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

During the Manhattan Project era at Hanford, environmental controls of today were not followed. Industrial toxins were routinely poured on open fields, which contaminated groundwater. Now billions of dollars are spent each year, and for years to come, on site clean up.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

The Hanford Site tour buss passes the T Plant/Canyon processing facility. After uranium fuel rods/slugs were irradiated in Hanford’s reactors, they were transported to the center of the site by train to chemical reprocessing facilities, also known as “canyons” because of the appearance inside of looking like a long, narrow canyon. The first canyon we saw on the tour was T Plant, which was built during World War II and was the first to process Hanford reactor fuel to obtain the small amount of plutonium that was created in fuel rods during the irradiation process inside the reactors.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Hanford’s Environmental Restoration Disposal Facility in the center of the Hanford Site is a massive landfill regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Built in 1996, ERDF accepts low-level radioactive, hazardous, and mixed (both radioactive and chemically hazardous) wastes that are generated during the cleanup activities at the Site. It does not accept any non-Hanford waste. Approximately 16 million tons of contaminated soil and debris from cleanup have been disposed of in ERDF since it opened. Most of the waste came from hundreds of buildings (that have been torn down) and hundreds of waste sites that have been cleaned up near the Columbia River, which flows through the site.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

The Plutonium Finishing Plant covers about 14 acres and was the end of the line in the plutonium production process at Hanford. The facility produced nearly two-thirds of the nation’s supply of plutonium (metal and oxide (powder)) for the U.S. nuclear weapons program during the Cold War. The facility operated between 1949 and the late 1980s. About 70 percent of the facility has been deactivated and cleaned out to prepare it for demolition in the next two years. Workers wear special suits and respirators to protect them from highly hazardous levels of plutonium and other radioactive material as they clean out plutonium processing equipment (such as glove boxes) so it can be removed from the facility, either prior to demolition or during demolition.

Colin Mulvany The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Share on Social Media